|

Website visitor Guy wrote to

request that I posted the article for the Supersweep hand-launched glider (HLG)

that appeared in the September 1974 edition of American Aircraft Modeler

magazine. It's good to know that there are still folks pursuing this simplest form

of model airplane building and flying - although there is nothing simple about building

and flying a contest-grade model. Another person, Ward B., wrote later to request

posting of the follow-up

Supersweep 22

article in the October 1974 edition of American Aircraft Modeler.

Supersweep Indoor Hand-Launched Glider

The Supersweep 22 has all the lines of a winner. The looks are

deceptively simple, though, as a quick reading of the construction sequence reveals.

By Ron Wittman, as told to Bob Meuser

On February 18, 1973, flying in the old Marine dirigible hanger at Santa Ana,

Ron Wittman made flights of 90.0 sec. and 88.7 sec.-the best two flights in the

series of nine - to establish an official AMA National Record for Indoor Hand-Launched

Gliders, Category III (unlimited ceiling height).

A couple of lucky flights perhaps, made under ideal conditions? Hardly! Rather,

during a year of intensive effort (backed by nearly two decades of previous glider

experience) Ron inched his way toward the record with a series of increasingly successful

designs. Ron made 90 sec. twice, dozens of flights over 85 sec., and only rarely

a flight under 80 sec. And the conditions? The worst imaginable! If the launching

was the slightest bit off, a collision with a parked helicopter was inevitable.

At the 1973 NATS, flying a light straight-dihedral version of the SS22, Bucky

Servaites won the IHLG event in Open Class. And while we were polishing up this

story, Ron's 11-year-old son, Steve, who looks scarcely big enough to carry a 22"

glider, let alone throw one, established a Junior National Record with a two-flight

total of 127.2 sec. That should permanently lay to rest the myth that small people

should fly small gliders.

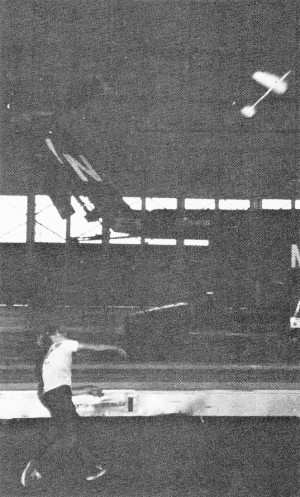

Steve Wittman, the author's 11-year-old protégé, set a Junior

National IHLG Record with the Supersweep. He sure showed dad that record-setting

can be a family affair.

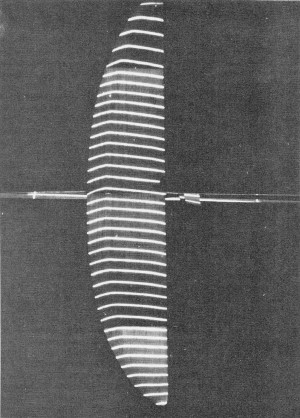

This eerie looking photo is an illumination of the wing with

"sheets" of light to show the airfoil section. The depth is exaggerated, especially

on the ,right wingtip. One can clearly see the tip wash-out, as well as the wash-in

on the left panel.

C-grain or quarter-sawed balsa, as shown here, is very resistant

to bending across the width of the sheet. Since it resists warps, it is essential

for true tail surfaces.

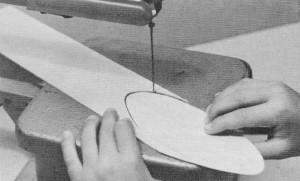

All parts should be jig-sawed to outline, or cut with a sharp

single-edged razor blade.

Final shaping to outline is done with coarse garnet paper.

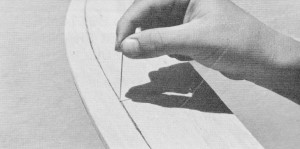

The high point of the wing is marked with pin holes in the partially

shaped wing. The holes remain visible as the sanding progresses.

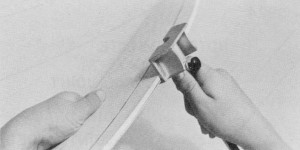

A handy gadget for marking the leading edge is a cabinet maker's

gauge. Accurate marking is essential.

A razor plane saves time, but can cause problems if not properly

used. Note that the cutting edge is angled 45° to the direction of the stroke.

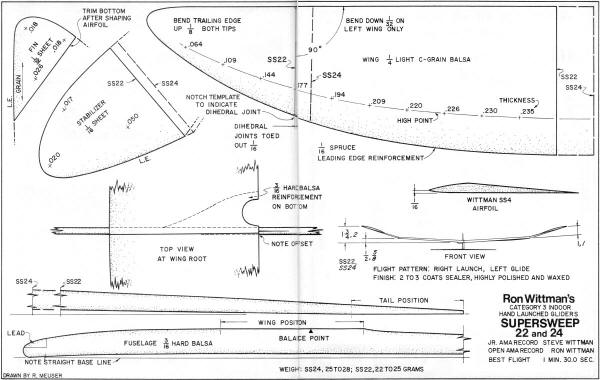

Ron's record was set with the SS22. However, he has actually surpassed his record

by a half second using a 24" span version. While the difference in flight times

is not significant, Ron feels that the Supersweep 24 has more potential than the

SS22, and is currently flying only the 24. The plans are basically those for the

22, but the minor modifications required to stretch it to the 24 are also indicated.

The Supersweep incorporates distinctive design features that might be applied

to any design to advantage. The most noteworthy features of the design are the airfoil

section, the high aspect ratio pointed-tip wing planform, the manner in which the

thickness tapers toward the paper-thin tips, and the severe wash-out in the wingtips.

The design of the glider, however, is only one of many factors required for success

in IHLG. Other important factors include: the construction and finish, proper trimming

and adjustment, the athletic factors - strength, stamina, and control - that result

in a powerful, consistent launch, and a long list of psychological factors including

the will to improve, and the persistence to view failure as merely a temporary set-back.

Although there are probably a number of modelers who can build as good a glider

as Ron Wittman, I doubt if there are any who can build a better glider. Since we

have not chosen to emphasize the importance of each step as we consider it in sequence,

we do emphasize that every step in constructing and finishing an IHLG is important

and must be done with care. We strongly urge you to follow these instructions to

the letter. Then, if you think you have a better way of performing a particular

operation, or if you wish to try a different method later, you will have a point

of reference. The following description applies to a right-handed person. For lefties,

of course, everything is reversed.

Selecting The Wood: The wing, being the heaviest part of the

glider, must be made from light wood, or the glider will be overweight. A piece

1/4 x 3 x 36" should weigh no more than 30 grams; a piece 4" wide, 40 grams. If

such light wood is not available, the wing will have to be made thinner and possibly

slightly undercambered, the spruce leading edge might have to be omitted, and you

will have to be extremely careful not to apply too heavy a finish. C-grain or quarter-sawed

wood - the kind showing iridescent specks on the surface - is ideal. The wood should

be flat, and the grain should be straight and parallel to the edges. The piece should

balance very close to its center. If a piece of uniform density cannot be found,

the heavy end should be toward the left wing tip, and the hardest edge should become

the leading edge. Usually, suitable 4" wide material is not available, so the wing

blanks must be made by gluing two narrower strips together. Be certain that the

edges to be joined are straight and square. Use a white glue - Franklin Titebond

is an excellent one.

For the tail surfaces, perfectly flat C-grain wood is essential. The wood should

be light, but not so light as to be flexible or mushy. Lack of flatness or stiffness

will cause the tail surfaces to deflect or vibrate during the 80 mph launch, and

that will decrease the launch altitude, or result in a smashed glider.

For the fuselage, select a piece of stiff, medium weight straight-grain 3/16"

balsa sheet, preferably with some showing of C-grain. Compare the weight, stiffness,

and straightness of several pieces, and select a piece that is as stiff as possible

but not too heavy. It is difficult to set down hard and fast rules; selecting fuselage

wood requires judgment that can be gained only by experience. The finger brace can

be made from scraps of the same piece.

Laying Out The Parts and Cutting To Outline: Make cardboard

templates for the wing and tail surfaces. Transfer the outlines to the balsa by

tracing around the template with a ballpoint or sharp nylon-tip pen. For the wing

and stabilizer, only a half-template is required (flip the template to get both

sides). Note that the wing is to be made in one piece, then cut into four sections

and rejoined after the sanding has been completed.

Cut all of the parts to shape, using a power jig saw or a new single-edged razor

blade. The blade must be sharp, or it will tear or compress the soft wood. Cut no

closer than 1/32" to the outline, then block-sand each part to its final outline

using 320 garnet paper. Using the template, mark the centerline of the wing. Balance

the wing blank along the centerline, and turn the blank so that the heavier side

becomes the left wing.

The spruce-reinforced leading edge is well worth the effort it takes to apply,

provided that the model is not in danger of being overweight. It minimizes damage,

and makes it easier to accurately form the front portion of the airfoil. A piece

of 1/16 x 1/8" spruce is glued, to the leading edge, flush with the bottom surface.

When the sanding of the wing is completed, only a hair over 1/16" of the original

1/8" depth remains. Soak the spruce in water first, or simply pre-curve the spruce

by drawing it between the fingers. This will place smaller demands on the strength

of the glue joint. However, as the curvature of the leading edge of the Supersweep

is gentle, this process is not essential.

Sanding: Make two balsa sanding blocks, each 3/4 x 3 x 11".

Round off the long edges slightly. Each side of the block is covered with paper

of a different grit number. No. 180 and 280 garnet paper are used for rough and

final shaping, while 320 and 400 "wet or dry" silicon carbide paper are used for

final thinning and smoothing. This stuff is expensive. Don't use a cheaper grade.

Ordinary "flint" sandpaper is far less suitable.

Cut the paper into strips 1/2" wider than the sanding blocks. Stick it to the

block with contact cement and wrap the edges up around the sides of the block. While

balsa is about the softest material anyone would think of using sandpaper on, it

dulls sandpaper rather quickly. Replace it as soon as it begins to lose its cutting

ability or becomes clogged.

A modeler's razor plane can be used to rough-out the top of the wing and the

fuselage, but it cuts too fast to use for shaping the tail surfaces. Use a new blade.

Hold the plane at an angle to the direction of the cutting stroke. Soft balsa is

difficult to plane. If it doesn't plane smoothly, or if it leaves streaks of uncut

wood, forget the plane and use sandpaper for the whole job. Don't use a thin blade,

a hollow-ground blade, or a stainless steel blade. Since Gillette made their Blue

Blades "super," the best blades are industrial paint-scraper blades.

Any good book on woodworking, some books about model planes, and your next-door

neighbor, will tell you that the proper way to sand is parallel to the grain of

the wood. Hogwash! Sand directly across the grain, at an angle to the grain, or

with a circular motion. If you sand with the grain, the balsa comes off in long

strings that simply clog the sandpaper and compress the wood.

Use as coarse a grit as you can get away with. Switch to a finer grit only when

the coarser grit cuts too fast for good control. Beginners often switch to a finer

grade too soon in an attempt to get a smooth surface; then, finding progress is

too slow, they bear down and crush the surface fibers of the wood. Never bear down!

That will compress the wood. It will expand later and ruin the airfoil shape. If

you feel you aren't making sufficient progress, go back to a coarser grit, replace

the sandpaper with fresh stuff, or go watch TV until you get over the feeling, but

never bear down!

All sanding should be done while the part is held against a hard, flat, clean

surface. A piece of 1/4" plate glass with at least one edge ground straight and

true is ideal, but it can be dangerous. A lamp placed under the glass will aid in

judging the thickness as the sanding progresses. Alternatively, simply hold the

piece up to the light to check the thickness, but do it often! A Formica-covered

sink cut-out, sometimes available at cabinet shops or lumber yards, is good too.

Wing and Tail Surfaces: Sand the bottom surfaces of the wing

and stabilizer blanks perfectly flat and smooth, first using 320 paper, and finally

400. Be especially careful not to round-over the edges or the tips. Mark a line

along the leading edge of the wing exactly 1/16" above the bottom surface (a cabinet-maker's

marking gage does the job nicely). Sand the upsweep of the bottom of the leading

edge. The upsweep starts 3/8" back from the leading edge and curves up uniformly

to the marked line. To avoid tearing off the spruce strip, it is best to sand toward

the wing.

Before shaping the top of the airfoil, sand the wing to the proper thickness

at each station, as shown on the plan. Note that the taper toward the tips is quite

severe compared to other gliders, and that the tips are quite thin and fragile.

Using a cardboard template, draw a line on the top surface with a nylon-tipped

pen to indicate the high point of the airfoil.

Next comes the most critical part: shaping the top of the airfoil, it is essential

that the high point be kept sharp. I had difficulty doing that, until I started

using the following method. (Ron sands the top surface freehand without recourse

to such crutches as this, but I don't have his dexterity.)

Secure a strip of masking tape to the top of the wing, so that the rear of the

tape is along the high-point line. Sand the rear portion of the wing to shape. The

tape will not only serve as a guide, but since it does not sand as readily as balsa,

it will prevent accidental cutting into the front part of the airfoil. Note that

the top of the airfoil is a straight line from the high-point to the trailing edge.

If you accidentally sand into the tape, replace it.

When the aft portion of the airfoil is completed, remove the tape - carefully,

so as not to rip up shreds of balsa - and apply masking tape with its front edge

aligned on the high-point line. Then sand the front part of the airfoil in a uniform

flat curve down to the marked line on the leading edge. Note that the leading edge

is sharp. The shape of the airfoil section is extremely critical, so refer to the

plans.

Sand the top of the stabilizer to the prescribed thickness, then sand in the

airfoil shape. Sand the rudder similarly, but work back and forth from one side

to the other to ensure a symmetrical section.

Ron doesn't actually measure the thickness of the parts. He knows by the feel

of the parts. He knows by the feel of the part, and by how the light shows through

it, when he has the part to the thickness he wants. But, in order to duplicate Ron's

Supersweep, you will have to measure the thickness somehow. A one-inch micrometer

caliper would work, except for the fact that the throat of the mike is often not

sufficiently deep. The throat can be ground deeper, or a 1/4" extension can be cemented

to the fixed anvil so that the deepest part of the throat is utilized.

A less expensive alternative is to use a machinist's outside spring caliper and

a ruler with fine divisions. To prevent the tips from gouging the glider parts,

balsa "feet" may be epoxied to the tips. Still another way is to measure from the

work surface up to a straightedge laid across the top of the wing (equalize the

measurements on both sides). The proper thicknesses of the various parts are indicated

on the plans.

Fuselage: Sand the fuselage to an oval cross-section. Be sure

not to round the edges in the regions where the wing and stabilizer are to be glued.

Here is how you can check to determine whether the fuselage has been sanded down

enough: - or too much! Clamp the fuselage to a table with the trailing edge of the

wing mount at the edge of the table. Hang a 100 gram (3 1/2 oz.) weight on the tail

boom at the stabilizer LE position. The extreme end of the boom should deflect no

more than 1/2".

The next step will be the most difficult. Take all the finished components, put

them in a safe place, and wait for the October issue of AAM. Don't attempt to glue

anything together, since there are subtle techniques involved, especially Ron's

"magic potion" finishing techniques. If you are impatient, make a duplicate set

of parts and complete an SS your way. Next month, finish one Ron's way and compare

them. You'll be shocked at the difference proper methods can make in better flight

time. Until next month, happy hand chucks!

<click

for larger version>

Notice:

The AMA Plans Service offers a

full-size version of many of the plans show here at a very reasonable cost. They

will scale the plans any size for you. It is always best to buy printed plans because

my scanner versions often have distortions that can cause parts to fit poorly. Purchasing

plans also help to support the operation of the

Academy of Model Aeronautics - the #1

advocate for model aviation throughout the world. If the AMA no longer has this

plan on file, I will be glad to send you my higher resolution version.

Try my Scale Calculator for

Model Airplane Plans.

Posted June 8, 2012

|