|

Well-known

modeling editor Bill Winters waxes wonderingly about whether the

"theoretician" modelers who use "wind tunnels, slide rules, [and]

adding machines" might really be gaining an edge over the "rule-of-thumbers"

who pioneered the basic precepts of various model aircraft design

and operation through trial-and-error processes. By removing environmental

variables like wind, thermals, and terrain, he considers how recent

gains in indoor events have rewarded renowned "thinker" type modelers

with great advanced in record performances. No Strings Attached

By Bill Winter Bill Winter takes a look at engine

break-in systems, provides much data on what happens inside there.

Should

you break in a new engine? Ask your modeling buddies and you'll

get answers ranging from yes by all means, through all shades of

maybe-sometimes to it's a waste of fuel. Should

you break in a new engine? Ask your modeling buddies and you'll

get answers ranging from yes by all means, through all shades of

maybe-sometimes to it's a waste of fuel. If these answers

baffle you, just don't ask the guys who say yes, how they go about

loosening up a scrawnchy mill. Merlin - would have been right at

home with his incantations, fiery circles and stuff. Can't

remember whether or not the Brown Junior required breaking in. The

prehistoric Junior apparently got awfully hot - but it kept running.

Fins became purple. We do know that from the late thirties until

after the war, when glow plugs and "shoe polish" fuels came on the

scene, engine breaking-in was de rigor, whatever that is.

It was nothing to clamp your new Bantam to a bench and let it

howl from dawn to dusk in the back yard. Neighbors - some of them

anyway - took kindly to ambitious young men who strode the path

of Lindbergh. (Today they call the gendarmes or the guys in white

coats.) Engine producers like Benny Shereshaw made their engines

so tight you had to run them for hours. Recall OK's post-war Mohawk

.29, which we turned over with a hand drill - the Merlin (not the

sorcerer this time) was another. We remember Keith Storey telling

us that the first team race put on in California was won by a Mohawk.

Further, our number-one boy fledgling flew the family Mohawk for

two years in Ukie and it hadn't begun to wear. Post-war the

arguments began. We suspect Half-A and small glow engines in general

had a lot to do with this for, as we know today, small engines seem

ready to give their all, whereas many big engines are prima donnas.

You've got to plead with them, like pushing the aft end of a mule.

(Hi Johnson tells us a good reason why, but more of this anon.)

Now the best Torps we ever had included the first two-speed

.19 - personally we loved the older Torpedo of the late forties

before everyone went rpm crazy - which Ted Martin ran 10 hours in

engine tests with all kinds of props, big and little, and at some

shattering rpm figures. That poor engine afterwards wore out three

Live Wires and was hotter than ever when some fool drove a station

wagon over the nose end of the last LW. The other hotter-than-hot

Torp was a .23 that one of the sprouts pilfered from our hope chest,

ran wide open new in Ukie stunt, leaned out, piled into the mud,

and so on. For 18 subsequent months that .23 struggled valiantly

with our seven-pound rudder job.

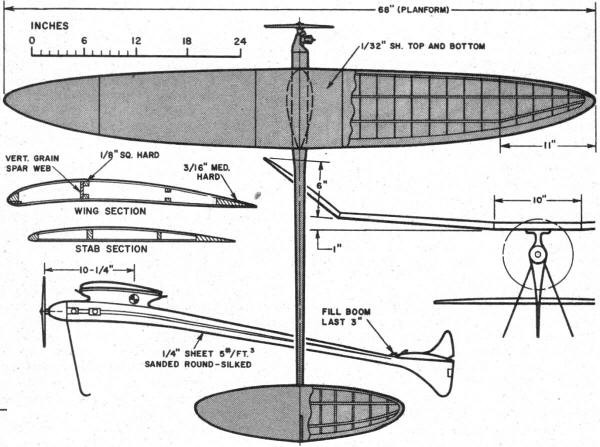

"Snicker": J.M. Trego's FAI Power. Wingspan,

68" (platform); 40-60 ellipse; Wing Root chord, 9"; Aspect ratio,

9"; Wing area, 445 sq. in.; Stab root chord, 6 1/2"; Stab area,

120 sq. in.; Wing incidence, four degrees; Stab incidence, 3 1/2

degrees; Center of Gravity, 70%; Wing airfoil, Goldberg G-610; Stab

airfoil, 6.8% at 30% (flat bottom).Of course,

we broke in many engines for hours on end. In the air they over-heated

and died. One of them had so much compression it wind-milled in

fast glides. The truth of the matter is that some modern

engines require no breaking in (and come to think of it, whoever

heard of breaking in an Arden; we turned 12-inch and cut-down 14-inch

props on a .19 on 90-degree days) and others will be ruined if not

run-in. Have had Webra Diesels, for example, that would freeze if

leaned out within four hours - but when they came-in they'd outlive

a turtle. Two buddies have Super Tiger R/C's on the block for six

hours and the engines are not yet ready to handle multi chores.

Our Frog .09 diesels were still picking up rpm after 11 hours of

flying! There was one glow .09 of ours that wore out the bearings

before it broke in enough to fly! And so it goes. Now that

we have everyone suitably confused, let's listen to a man who knows

what he is talking about (for a change!). So many club papers have

picked up Hi Johnson's tips on breaking in engines that, on the

theory where there is smoke there must be fire, we consider now

the august pronouncements of one engine man. (If it turns out that

engine makers, like modelers, also argue the issue, we no doubt

will come back in due time to the break-in discussion.)

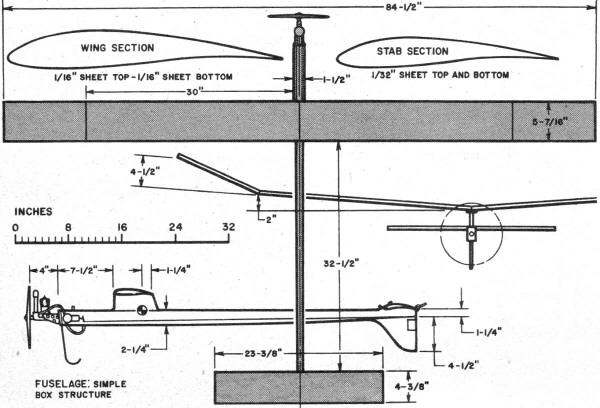

"Mozagotl": Werner Petri's 1960 FAI Power.

Wingspan 84 1/2"; Overall length, 53"; Wing area, 461 sq. in.; Aspect

ratio, 15.5; Stab area, 102 sq. in.; Wing incidence, zero; Down

thrust, minus 3 degrees; Side thrust, 1 degree; Stab incidence (power),

minus 2 degrees; Stab incidence (glide), minus 4 degrees; Center

of Gravity, 77%; Power, reworked Super Tiger G-20 (1959) with intake

extension (kadency effect). Auto-rudder and auto-stab trim operated

by single mechanical timer, auto-stab operated by bell-crank on

T.E. Machined dural engine mount with four synthetic rubber grommets

for vibration isolation.Having read Hi's very

useful data umpty-ump times we have learned something new, proving

that you can teach an old dawg new tricks. To boil it down, Hi describes

a kind of molecular stampede in the metal as it is machined, worked,

and treated during the manufacturing of an engine. (Incidentally,

some guy on the side lines tells us that it is always "engine",

and never "motor", because motors are electric). Manufacturing

processes, it appears, introduce stresses in the materials and the

mischievous molecules remain partially unstable after that, no matter

what. The crux of the matter is that the number of cycles of heating

and cooling that an engine must pass through to attain molecular

stability depends entirely on the molecular state of the metals

at the time of engine purchase. Having had two new .15's freeze

in the air, tossing expensive nylon props, and washers, into the

weeds - new sleeves and pistons coming up! - we'd say this molecular

state sometimes borders on anarchy. Anyway, the word is that

it's the first four or five minutes of running time (each time)

that counts, and not a three- or four-hour break-in run that only

frees the engine slightly. According to the Johnson Doctrine, many

short runs, never leaning out, allowing the engine to heat up and

cool off completely, bring law and order to the delinquent molecules.

The bigger the engine, the more the naughty molecules. And that

is why Half-A engines take little or no break-in time. Shucks, we

always thought the Half-A engine makers were more ingenious!

How about break-in fuel? Use a mild fuel (less than 12 per cent

nitro) for the first hour or two - on .15's and up, decrees Mr.

Johnson. For small engines, use the fuel marked "For Half-A" on

the can. Adjust the needle to medium rich (medium rpm four-cycle),

run off a five to seven-ounce tank. Repeat as many times as necessary

for at least 30 minutes running time. To this we add, don't overload

the engine with a big prop during break-in. Is "Theory"

Vindicated? Probably you, too, have noticed the growing

respect for "long hair" designers. Like breaking in engines, the

merits of theory as opposed to the rule-of-thumb school of design

has always been good for a rainy day argument. For many years the

American approach leaned toward rule-of-thumb. A lot can be said

for it. In the beginning, pioneers endlessly ground out models,

gradually changing this and that until they knew all the basic answers

on proportions, areas, dihedral, and so on. Some became authorities

- justly we think - by evolving formulas to express what they already

knew, so that others could apply the hard-won knowledge.

In the middle years, when modeling attained truly popular acceptance,

anybody who built a few jobs that flew fairly well could consider

himself a theoretician. To the rest of us some of these talkative

chaps were a pain in the neck. By reaction we became a bunch of

rule-of-thumbers. Oh, there were guys who thought, witness Goldberg

and the pylon gassie, but this was still a common-sense, though

impressively reasoned approach. That is, it didn't require wind

tunnels, slide rules, or adding machines.

Perhaps

we began to have nagging doubts about our instinctive disapproval

of "theory" when, in Europe men like Czepa, Hacklinger, Benedek,

Van Hattum, Lindner, Samaan, largely through Nordics, displayed

results that at least proved a man could be deeply theoretical and

a top flier at the same time. So effective was their approach that

until Gerry Ritz came along the U.S. had practically conceded it

could never match the Continentals in some areas. A rule-of-thumber

himself, ole Zeke, has got to concede the theory boys - the authentic

ones, not just every guy who decides to go into the theory business

for himself - must really have an edge. This superiority is hard

to evaluate because natural things - such as thermals and time limits

- don't exactly encourage, or maybe even justify, all-out theory.

But what has set us to thinking, is this achievement of Hacklinger's,

a 44-minute flight in indoors. Don't spoil it by telling

us the flying site was super, but it seems to us that when a deep

thinker like Hacklinger, who long has held wide respect, on relatively

short notice (indoor is practically new in Europe) comes up with

a performance like this, he has demonstrated that "model engineering"

is equated with efficiency. Though all designs that can max

interminably seem the same, we shall suspect from here on in, that

one must always be better than all the others. It is nice to have

the best. Back to the drawing board!

Posted June 8, 2013

|