|

It is hard to believe there was a time

that a production-level VTOL (vertical take-off and landing) aircraft would be a

big deal, but that was the case in the late 1960s and early 1970s when the

Harrier

"Jump Jet" arrived on the scene. British aircraft manufacturer

Hawker Siddeley

was the innovator. I remember being TDY (temporary duty) at

Fort Campbell,

Kentucky, sometime around 1981, while in the USAF, having gone there to pick up a mobile

TACAN (tactical air navigation system) unit that was on loan

from our Robins AFB, Georgia home base. We were going to load the hardware

into a pickup truck when we saw a couple jets zoom overhead and then go around for

a landing. It was very strange to notice how they seemed to be taking much longer

than normal to arrive over the runway, and then it occurred to me that they must

be Harriers. It was fascinating to watch the pair hover side-by-side, and then softly

touch down and then taxi to the tarmac area. We had to leave before they took off

again so I never got to see that - bummer. Since that time I have seen a few both

take off and land at airshows. It never gets old.

The Harrier Needs No Runway

Five RAF Harriers cruise in formation. U.S. Marines also will

use this ship.

Nozzles swiveled downward, this Harrier hovers on takeoff. Field

is just a pad.

With the world's first VTOL fighter squadron in operational service, the Hawker-Siddeley

GR Mk. 1 may also be built by McDonnell-Douglas.

By Don Berliner

Airplanes are great - but who needs airports?

Airplanes need them, of course, and it's a real problem. Airports take up hundreds

of acres of land, with only a few narrow strips of it in actual use. The convenient

ones are being gobbled up and turned into housing projects, while new ones big enough

to handle the latest types of airplanes are so far out of town that the people in

charge are seriously talking about building railroads for access to them.

Nearly everyone has ideas for solving the problem, but the simplest solution

would be to get rid of runways, so that airports can be small and convenient. This

is accomplished by developing airplanes that take off and land straight up and down.

Simple, huh? So simple that it appealed to the first man who seriously thought about

making a flying machine, none other than Leonardo da Vinci, back in the days when

Christopher Columbus was sailing West to find the East.

Leonardo worked on ornithopters, parachutes and helicopters - all of them for

mainly flying up and down without first having to run along the ground for a mile

or two. None of the great Italian's designs ever got off the drawing board, as far

as we know, and there is good reason to doubt that any of his farsighted designs

for man-powered flight would have flown.

A mere 450 years later, Igor Sikorsky and Gerd Achgelis combined ingenuity with

modern engines to produce the first workable helicopters. This giant step led to

great things, but not even several decades and billions of dollars have been able

to make the helicopter go very fast.

If a machine that goes straight up won't go fast, why not take a fast machine

and make it go up? This challenge caught the imagination of many engineers some

20 years ago, and the novel concepts flowed like light oil. Convertaplanes with

folding wings or folding rotors. Airplanes with rotating engines and swiveling wings

and tilting propellers. And the most amazing conglomeration of flaps and slots and

slats and gadgets of all manner. Money poured in, and the props/rotors/fans went

around, and sometimes the things got off the ground. But mostly they made a great

deal of noise and didn't go much of anywhere. And even when they worked, they were

so expensive to operate that nobody would have bought one, so they never went into

production.

Still people tried, for if the extremely complex problems of control and safety

and economy could be solved, aviation history would be made. From each unsuccessful

attempt came further knowledge and the increased conviction that the idea eventually

would work.

One of the ideas was for vectored thrust and came from a French engineer, Michel

Wibault. In 1954, he proposed an aircraft with multiple jet exhausts which could

be directed anywhere from straight down to straight back. His own government failed

to show interest, so he offered the idea to the U.S. Mutual Weapons Defense Program,

which turned it over to Bristol Aero-Engines Ltd., in England, for research.

While the hardware underwent major changes, Wibault's principle remained the

same. In 1957, after the idea had come to the attention of the late Sir Sidney Camm,

designer of the Hawker Hurricane, and then the head of Hawker Aircraft (now Hawker-Siddeley)

things began to jell. By late 1957, the shape of the Hawker P. 1127 had been placed

on paper. It would be powered by an 11,000-lb. thrust Bristol-Siddeley BS.53 Pegasus

turbojet and a pair of swiveling nozzles on either side of the fuselage would point

down for takeoff and landing, and back for flight. The basic shape was set for the

entire family of VTOL fighters: short, highly tapered wings, tandem main landing

gear in the fuselage with semi-retractable outrigger wheels at the wing tips, and

a big bubble canopy set far forward.

The prototype flew tethered on Oct. 21, 1960, and made its first free flight

on March 13, 1961, with Hawker chief test pilot Bill Bedford at the controls. The

forerunner of the Harrier worked, and it worked well. But others before it had gotten

this far and then slithered to a halt. The P.1127 began as a privately financed

project of the manufacturer and was given a big boost with American funds. But without

orders from its own government, this promising project would go down the drain.

NATO, which had shown interest in the VTOL concept, announced in early 1961 its

need was for a supersonic VTOL fighter, so Hawker-Siddeley launched its P.1154 program.

However, the P.1127 was kept alive by a most unusual move: the U.S., Britain and

West Germany decided to form a tripartite (three-country) squadron. Its purpose

was to study the operations of VTOL fighters by using nine Kestrels which were improved

P.1127's.

The Kestrel Evaluation Squadron, which may be without counterpart in aviation

history, was formed in October, 1964, and actual trials were run from April to November,

1965. More than 500 hours of flying and more than 1000 takeoffs and landings contributed

greatly to the knowledge of flying VTOL aircraft in a wide variety of situations,

rather than under the restricted conditions of most previous VTOL operations. The

Kestrel showed it was able to do the job for which it had been designed, but no

orders came in.

Rising vertically from a dirt field, a Harrier displays military

flexibility.

Huge airscoops feed the 19,200·lb. thrust Bristol Pegasus. Top

is supersonic.

When the test squadron was dissolved, six of the Kestrels were sent to the U.S.,

where some of them became known as XV-6A and were operated by the USAF and NASA

to develop V/STOL techniques and all-weather flying. Slowly the P.1127 was proving

itself to be a thoroughbred and not just one more flying test-bed. Serious interest

was beginning to develop.

The once-promising supersonic P.1154 got some support from the RAF, but then

was dropped, to be replaced in 1965 by the next step in the P.1127 series, the Harrier.

The British government acted slowly and cautiously on the radical idea, but nevertheless

faster than any other government was moving. The first Harrier flew on Aug. 31,

1966, and the other five development aircraft were airborne by the following summer.

Meanwhile, the first true production order had been placed by the RAF for 77

GR Mk.1 fighter-bombers and 13 two-seat T MK.2 trainers. The first single-seater

flew on Dec. 28, 1967, and the first trainer on Apr. 24, 1969. Others followed quickly,

and on the first of July, 1969, the world's first operational VTOL squadron was

formed. It had taken a long time, but a vertical takeoff aircraft finally was in

service.

Shortly before this historic event, another chapter in the story of the Harrier

was written and still is having repercussions. The $140,000 Daily Mail Air Race

between downtown London and downtown New York was seen by many as a convenient way

to show off the performance of the Harrier to U.S. officials who were prospective

purchasers. RAF Sqdr. Ldr. Tom Lecky-Thompson made the long trip, including slow

portions on the ground in both cities, in just over six hours, landing near the

United Nations building on Manhattan Island. Thousand of bystanders were amazed,

the press was properly impressed, and officials of the various U.S. air services

reacted as hoped.

The Marine Corps decided. the Harrier was exactly what it had been looking for

and placed an order. The first AV-8A produced expressly for the USMC came off the

Hawker-Siddeley assembly line in September, 1970, to be followed by 11 more in the

first group and then a second. The first were scheduled to be delivered to the Naval

Flight Test Center at Patuxent River, Md., in January, 1971. After acceptance trials

have been completed, they will go into service with Marine Corps units operating

off aircraft carriers and will be flown by pilots already trained by the RAF.

If all goes well, more than 100 additional Harriers will then be built on license

by McDonnell-Douglas. Other than the English Electric Canberra, built by Martin

as the USAF's B-57, the Harrier will be the only foreign aircraft put in service

by the U.S. since World War I.

A harrier, by dictionary definition is a long-distance runner. The Harrier now

making flying history is one man-made bird that doesn't have to be a cross-country

runner.

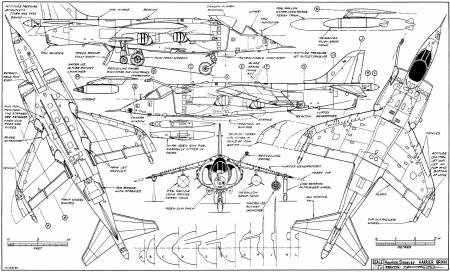

Harrier Jump Jet 5-View Drawing

Specifications: Harrier GR Mk.1

Dimensions:

Wingspan - 25' 3" (29' 8" with long-range tips)

Length - 45' 8"

Height - 11' 3"

Wing Area - 201 sq. ft. (217 sq. ft. with long-range tips)

Power - 1 Rolls Royce Bristol Pegasus 101 @ 19,200 lb.

Empty Weight - approx. 12,000 lb.

Maximum Hover Weight - approx. 16,000 lb.

Gross Weight - approx. 22,000 lb.

Performance:

Maximum Speed - over 720 mph

Maximum Diving Speed - over Mach 1.25

Service Ceiling - over 50,000'

Ferry Range (without refueling) - 2300 mi.

Minimum Take Off Distance-0' 0"

Posted February 2, 2019

|