|

Of course the allusion in this

title, "'The Better to See With...' Plexiglas Machine Gun Turrets" is to "Little

Red Riding Hood." Do you remember the scene in "It's a Wonderful Life" where

Sam Wainright's

new factory has a busy production line turning our Plexiglas canopies? "I

have a big deal coming up that's going to make us all rich. George, you remember

that night in Martini's bar when you told me you read someplace about

making

plastics out of soybeans?" George passed it up and Sam got rich. Plastics

were rarely found in products prior to World War II. A shortage of metal, glass,

and rubber (recall the surplus materials collections) gave birth to a thriving

plastics industry that included aircraft canopies. Prior to that, you will note

the flat glass window panes used in windshields and canopies built in segments

using metal frames. The one photo of the line worker applying a coat of Simoniz

to the Plexiglas canopy reminds me of the company's slogan

"Motorists wise, Simoniz,"

which was made famous again in the original story version of "A Christmas

Story," by Gene Shepherd, entitled "Duel

in the Snow, or Red Ryder Nails the Cleveland Street Kid."

"The Better to See With..." Plexiglas Machine Gun Turrets

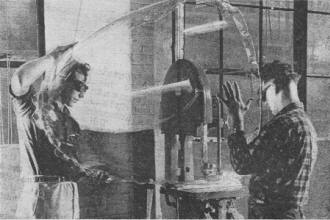

Edges of the sheet are clamped to form before the material

cools. At 200 degrees, Plexiglas may be handled by workers wearing ordinary

cotton gloves.

Workmen cut to shape a rough form of the plastic. This turret covering is the

Nose of a Martin B-26. Material is said to be more transparent than glass.

With the advent of streamlining and covered machine gun turrets, a good plastic

was needed. Of all that have been tried to date, Plexiglas is rated as being the

best.

by Ralph Tekel

At the Great Air Corps training center of Randolph Field, Army flying instructors,

used to give fledglings the following advice: "Try to make a ball and socket joint

of your neck. Keep your head and eyes moving, watching the whole sphere. Remember

you're not driving down a highway where traffic is on one level; in the air another

ship can come at you from any direction, so if you expect to become good military

pilots you must try to look in all directions at once."

Good advice, no doubt - but also a pain in the neck!

That advice was given in all sincerity, and the reason is obvious. Surprise is

the basic advantage in aerial warfare. The unexpected attack has a greater chance

of success than the anticipated one for there is neither time nor opportunity for

the enemy to counter-attack.

In the design of a modern bomber, fighter, or anything that has wings and machine

guns, great emphasis is placed on the best possible visibility for the pilot, gunners,

and bombardiers. Not so, long ago such emphasis carried out on this characteristic

necessarily meant sacrifices for other qualities. But the latest method's assuring

unlimited visibility have come a long way since the old celluloid windshield and

helmet and goggle days.

The quickening pace of military aviation development imposed upon the engineers

and designers the responsibility of protecting the crews and at the same time providing

them with unobstructed views from all conceivable angles. Logically, the use of

transparent plastic sheets, which have paralleled aircraft development so closely

in the last six years, provides the solution of the designers' problem.

The acrylic. plastic sheets developed from synthetic resins are outstanding in

colorless transparency, chemical resistance, and stability against weathering and

aging. The manufacturers call these sheets Plexiglas.

Plexiglas is actually more transparent than glass and retains this feature in

spite of glaring sunlight, and extremes of temperature and humidity encountered

by the aircraft. It is less than half the weight of glass, and is yet able to withstand

greater impact.

As a plastic, Plexiglas can be formed to the two or three dimensional sections

required for streamlining nose turrets, cockpit enclosures, blisters, and power-driven

turrets. It is also easy to cut and drill and can therefore be mounted in lightweight

extruded aluminum channels to eliminate the necessity of braces and supports that

so seriously hamper perfect visibility.

Note the smooth streamlining achieved on the Lockheed P-38

Lightning's cockpit enclosure.

A close-up of the nose installed on the Martin B-26 which

embodies latest combat features.

Impervious to the action of gasoline, acids, and oil, Plexiglas is polished

with Simoniz.

Plexiglas is known technically as methyl methacrylate resin. The basic substances

used in its manufacture are made from coal, petroleum, air, and water. When bituminous

coal is used, it is heated in a coke oven and the byproducts are collected. Among

these is a gas called propylene which, by a series of chemical reactions, is transformed

into the well-known constituent of airplane dope, acetone. A further conversion

of acetone produces a basic material called unpolymerized methyl methacrylate. This

can also be made from byproducts of petroleum. From here the basic material is polymerized

at the ideal temperature, which was found to be 60 degrees centigrade.

Polymerization is merely the attaching of one molecule of methyl methacrylate

to another and still another in a chain until they intertwine and form a solid called

methyl methacrylate polymer - which is the technical term for Plexiglas. The resultant

Plexiglas is a hard, bubble free, transparent plastic impervious to air, rain, and

acids. Gasoline, oils, fats, waxes, and destructive bacteria, moreover, do not effect

this material.

Considerable care is exercised in the making of a Plexiglas aircraft part. The

manufacturer starts with a flat cast sheet which is protected from dirt and other

foreign matter so that there will be nothing in or on the sheets to distort the

vision of the pilot or gun crews.

The cast sheet is suspended in a hot air oven until it reaches the best forming

temperature of 220-250 degrees Fahrenheit. After being heated, the Plexiglas is

pliable and cool enough to be handled by workmen wearing cotton gloves.

The molding form is generally made of either wood, metal, or plaster or a combination

of these three materials. The surface is carefully sanded and covered with outing

flannel or billiard felt to eliminate rough surfaces. Before the mold is made, however,

the airplane manufacturer designs the installation and usually submits preliminary

prints for study of the Plexiglas engineering and productions staffs.

For three-dimensional curves, the material is stretched across the form or, for

some sections, pressed between male and female molds. When cool, the formed she

e t is lifted off the mold and is trimmed to specifications. The adaptability of

Plexiglas allows it to be cut, carved, etched, engraved, turned and ground, polished

and even "welded" without leaving a seam. Fine tooth saws are used in trimming,

since they leave the piece. with relatively smooth edges.

The next step is machine and buffing operations. Holes are drilled to facilitate

insertion of bolts which hold the shaped form in aluminum channels. Inasmuch as

the surface of Plexiglas is softer than glass it is easily marred unless the proper

precautions are taken. In cleaning, no ordinary kitchen scouring compounds are used;

instead, Simoniz cleaner and polish satisfactorily removes minor scratches. Army,

Navy, and most commercial airplane maintenance staffs are equipped with portable

buffing machines which can remove the more serious damages that are likely to occur.

Polishing and buffing does not influence the life of Plexiglas and many panels have

already put in four or five years of hard service without appreciable loss of light

transmissions or general visibility.

Mounting Plexiglas sheets requires utmost care. Since it is resilient, undue

stress brought on in bolting and riveting operations are avoided to prevent high

pressures directly on the plastic itself. The use of shoulder rivets or a metal

tube spacer a few thousandths of an inch larger than the thickness of the glass

sheet protects the plastic from direct pressure. Most popular backing is rubberized

fabric, which is plastic enough to compensate for thickness variations in the sheet

or width variations in the mounting channels. Because Plexiglas is subject to thermal

expansion and contraction, as well as internal pressure because of airflow over

its surface, the rubberized material serves the purpose best and also makes the

edges watertight.

One of the advantages of Plexiglas sheet is that its edges can be routed and

beveled to set flush with the outside of the airplane's metal surface so that there

will be no protruding edges or corners to set up drag at high speeds. The availability

of sheets in sizes up to 45" by 60" gives the aircraft engineer the widest latitude

in designing transparent sections. For many purposes, 0.250" or thinner material

has proven satisfactory. On low speed ships and gliders, sheet as thin as 0.060"

to 0.100" may be used. Sections in high-speed planes are usually 0.125" to 0.150"

in thickness when they are less in area than one square foot. The material used

for landing light covers is usually thicker glass to allow for a routed edge.

Plexiglas has a specific weight of 1.1 against the 2.6 of ordinary glass - meaning

that the use of four square yards of Plexiglas for airplane windows brings a savings

of about 50 pounds of weight against that of plain glass of the same thickness.

Tests with Plexiglas of 1/8" thickness and plain glass of 1/4" thickness showed

that the former could withstand the onslaught of 8 to 10 times the number of blows.

When Plexiglas cracks it doesn't splinter like ordinary glass but breaks up into

large, dull-edged pieces. It is not bullet-proof; tests, however, have shown that

bullets penetrating Plexiglas usually leave a clean, round hole rather than shattering

a whole section. Its reaction to rapid fire of machine guns is just about the same

as that of bullets hitting the aluminum alloy covered sections of a fighting plane.

A further development for Plexiglas in the aviation field has been the use of

this material for housing radio and range finder antennae. Far from reducing reception

efficiency, Plexiglas housings cut down static as well as other interference to

an appreciable extent. Further, it is better in hail and sleet resisting than metal

housings.

Plexiglas' light weight, high impact strength, durability, and permanent transparency

plays an important part in our national defense scheme. Sheets of this same acrylic

plastic forms the windows, landing light covers, commander's domes, and machine

gun blisters on every type of military plane now being made. It is also rapidly

finding favor on commercial ships.

The manufacturer of Plexiglas is the Rohm & Hass Company, of Philadelphia,

whose shops are kept busy turning out the enclosures for today's and tomorrow's

high-speed, high-altitude military planes.

Posted August 26, 2023

|