|

Mr. Jon Lowe, the son of well-known columnist

Don Lowe, wrote to request

that I post this article on the Whiplash, which was originally published in the November 1974 edition

of American Aircraft Modeler. His father wrote a monthly column for AAM at the time, including in that

very edition. The Whiplash is a 20-size aerobatic plane designed for fast building and for pattern practice

when you don't want to drag out your full-size ship. Whiplash

Dick SarpolusIf you were in it while it was flying, you'd understand how this plane

got its name.

If weather conditions

in different parts of the country have an effect on aircraft designs, then the Whiplash is a result

of our northeastern (New Jersey) winter climate. I am primarily a pattern competition flier, and after

the last contest in October, I hang the current hot ship on the workshop wall until spring. I just don't

enjoy serious practicing in cold, wet, windy winter weather - I'd rather not risk a good pattern aircraft

in casual fun flying. If weather conditions

in different parts of the country have an effect on aircraft designs, then the Whiplash is a result

of our northeastern (New Jersey) winter climate. I am primarily a pattern competition flier, and after

the last contest in October, I hang the current hot ship on the workshop wall until spring. I just don't

enjoy serious practicing in cold, wet, windy winter weather - I'd rather not risk a good pattern aircraft

in casual fun flying. Our club field does see a lot of winter activity and, without the contest

season pressure, it is a lot of fun. Because of the weather, our winter flying is done a little differently

- we don't plan on a whole day at the field. Much of the time is spent with hot coffee in a handy car.

For this type of flying, a small, easily assembled plane (especially one that will fit in the

car assembled) is a real advantage. We observed some fliers who flew powered gliders exclusively and,

while this was not what we wanted (can't practice Class C maneuvers with a glider), the simplicity of

hand launching appealed to us. Elimination of landing gear would further simplify the plane and enable

better performance with a small engine. One characteristic we had to have to allow pattern practice

was full aerobatic capability. To be competitive in Pattern, you must fly a lot. To do all the flying

with the same aircraft would, of course, be ideal. However, that is not a necessity. The important thing

is to fly something that will perform all the maneuvers.

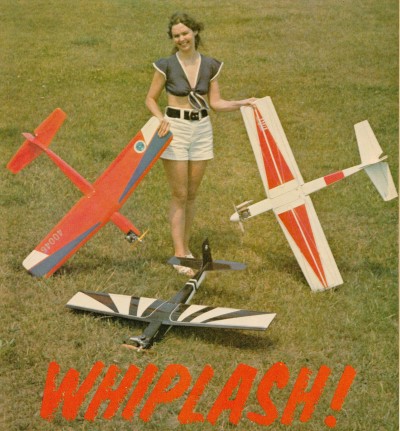

The angular lines of the Whiplash allow many variations in personalizing

the finish. Wayne Marcy did the eye-catching MonoKote job at the left.

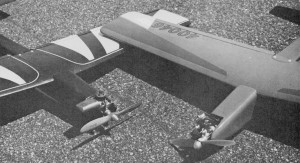

The sidemounted engine (right) ensures that the center of the

tank falls in line with the needle valve.

Dick uses transmitter

antenna to prod Arni Pederson into one of his statuesque launches.

Lynn Sarpotus gives some feel for the size of the model - large

enough for smooth aerobatics, yet small enough to dump in the trunk or back seat between flights.

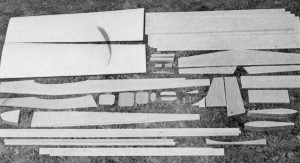

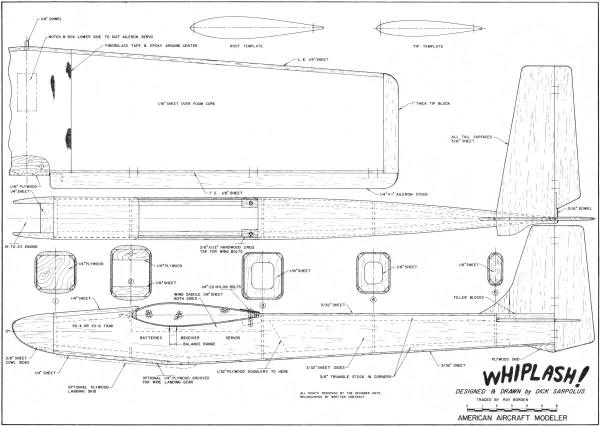

A minimum number of pieces makes the Whiplash not only simple,

but inexpensive to build.

A Whiplash with legs.

The landing gear might be essential in some areas (after all. it doesn't snow everywhere). Try skis

in place of wheels for an ROS (Rise Off Snow).

Don' think hat these desired characteristics result in a hot, "experts only" airplane. The Whiplash

is not a basic trainer, but it did turn out to be a good intermediate ship. Anyone who can fly basic

ships like the Falcon 56, J-Craft, etc., can fly our Whiplash. And the expert flier can have plenty

of fun without worrying about his top contest ship. We set led on 19 power to keep the size

down and still achieve acceptable performance. We would be using four channels, so the equipment weight

would be considerable. There are some good 19 engines on the market, and we felt this was as small an

engine size as possible. The wing would need to have a fully symmetrical airfoil for full pattern capability;

we wanted this plane to "feel" like a typical 60 competition ship. Wing planform would be tapered, of

course, with strip ailerons for ease of construction. Foam wing cores were de-sirable for a quick, easy,

rugged model. The wing would be top mounted, so we could hand launch and belly land. Competition

ships are exclusively low- or mid-wing now, but a top wing on a reasonable fuselage design doesn't change

performance noticeably. The fuselage was held to a minimum cross-section for the least possible drag

and weight. One area that could significantly help in weight was the radio equipment; we used a 600

mah battery pack and KPS-10 size servos. The newer mini-servos and lighter battery packs would make

a difference. Throughout the plan sketching, we stressed simplicity - we wanted to fly, not build.

Specs came out like this: 50" span, 390 sq. inches of wing area, 41" overall length. So many of

our local club members liked the concept that, with the help of the local hobby shop, we made several

dozen "semi-kits" which were sold at a nominal charge. One alteration of the original concept

was the addition of landing gear. I like the plane better without it, but after our club put down a

blacktop strip 250 x 40', we did want to use it on occasion. I added the gear to my completed plane,

made it removable, and really haven't used it very much. That covers the design. Although the

major design influence was our local weather conditions, we feel the result may appeal to many fliers.

CONSTRUCTION I would suggest cutting out all the parts first, making your own kit, rather

than the cut-as-you-go approach. It will save time. Wings first - most clubs now have foam cutting ability

and it sure makes for an easy wing. Foam wing construction has been covered many times, so I'll

emphasize only a few points. To insure a smooth job, join the 1/16" balsa skins, truing the edges first,

taping the seams, then gluing and sanding before cementing the skins to the core. The best contact cement

I have found is Southern's Sorghum or Mini-Flite's Maxi-Tac. I skin the cores first, true the leading

and trailing edges with a long sanding block, then glue on and finally shape the leading and trailing

edge wood. Tips come next; center section is joined and reinforced with fiberglass cloth and epoxy.

Aileron horns are installed, then the 1/16" plywood reinforcement for the nylon hold-down bolts.

Tail surfaces are simply 3/16" sheet balsa. Try to select light wood throughout and sand everything

well. The fuselage is a basic box, with triangular balsa in the corners to permit a well

rounded shape. The 1/32" plywood doublers add a lot of strength. The sides are parallel from the firewall

to the wing trailing edge, which makes it easy to align. I build almost the entire fuselage with five-minute

epoxy. The engine could, of course, be faired in more with balsa blocks shaped to match a spinner but,

again for simplicity I used side cowl pieces only. Glue the hardwood wing mount blocks securely

and drill and tap for the nylon wing bolts. There is not a lot of room for the radio equipment, so the

installation must be neat. The three servos in the fuselage should be installed as low as possible,

and the aileron servo should be installed as deeply as possible in the wing. The gas tank can be inserted

through the wing opening and held in place with foam rubber. We have used the Kraft nylon engine

mount and the Tatone aluminum mount. The models built so far have balanced pretty well without any added

weight; they do tend to be nose heavy, so try to use a light muffler and keep the radio equipment as

far back as possible, etc. We put the servos at the rear of the compartment, receiver in the middle,

batteries by the leading edge. If you use an engine larger than a 19, it might be well to shorten the

nose by 1/2" or so. A 19 seems to be the ideal size. I have flown four different Whiplash models, each

with different engines (a Veco 19, Supertigre 19, OS 19 and a Webra 20), and all performed about equally.

It is a good idea to put a skid of some sort under the nose section, or to even cover the bottom

with fiberglass or celastic. We adjust the carburetor to stop the engine on command and, if the prop

is set horizontal at compression, it will stop at that position. MonoKote or a similar material

is of course best from a weight and finishing time standpoint. Flying the model should present

no problems; if inexperienced, let a pro set it up for you. The rudder is only needed for certain maneuvers

and, if lack of a throttle doesn't bother you, I see no reason why it couldn't be flown two channel

(ailerons and elevator). With the fully symmetrical airfoil, it isn't going to float like a sailplane,

but it is pretty gentle. We sure don't need more pylon racing classes, but a 19 class with a design

like a Whiplash would be a lot of fun. If you can't get foam wing cores locally, contact me

at 32 Alameda Ct., Shrewsbury, N.J. 07701. Every project leads to another idea; after flying

the Whiplash and reading about the progress in electric power for RC aircraft, I feel an electric-powered

Whiplash would really be the thing for fun flying. Perhaps our next project will be an electric-powered

pattern-ability fun ship. The state-of-the-art moves ever onward!

Whiplash Plans

<click for larger version>

Notice:

The AMA Plans Service offers a

full-size version of many of the plans show here at a very reasonable cost. They

will scale the plans any size for you. It is always best to buy printed plans because

my scanner versions often have distortions that can cause parts to fit poorly. Purchasing

plans also help to support the operation of the

Academy of Model Aeronautics - the #1

advocate for model aviation throughout the world. If the AMA no longer has this

plan on file, I will be glad to send you my higher resolution version.

Try my Scale Calculator for

Model Airplane Plans.

Posted April 30, 2012

|