|

An

article covering a major R/C competition in one of today's modeling

magazines would be 90% color photos and 10% text. In 1967 it was

just the opposite, as this coverage of the "Fifth World Championships

of Air Gymnastics for Remote Controlled Aircraft" shows - and there

is no color to be found. Maybe the old adage about a picture being

worth a thousand words balances the equation. 43 pilots represented

17 nations on the French island of Corsica. Phil Kraft and his own

design Kwik Fli IV ruled the day. France and Germany took second

and third place, respectively. If you like reading about how the

early pattern radios, airplanes and engines were combined to wow

the crowds, this one is for you. Fifth RC World Champs

Seventeen nations - and 43 pilots - vied in hotly contested meet

at Corsica, sponsored by the Aero Club of France. Using models powered

by the big 60's, but distinctly smaller than those flown by the

competition, the United States' consistent performance gained both

individual and team honors. By Howard McEntee

The happy winners: Phil Kraft, USA, first; Pierre Marrot, France,

second; and Kurt Bauerheim, West Germany, third.

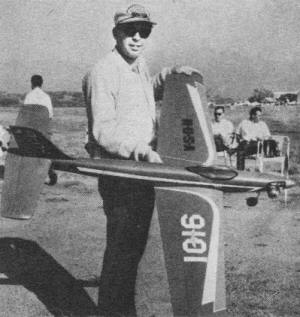

The winning combination: Kraft and Kwik Fli IV.

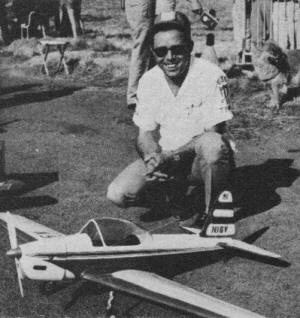

Doug Spreng and his fourth-place Twister.

In tenth place, Weirick with scale Chipmunk.

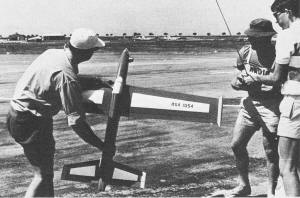

The South African team was an example of truly amateur enterprise;

none has any connection with the trade. Chris Sweatman, Rich

Brand, and Johnny Wessells.

Fifth World Championships of Air Gymnastics for Remote Controlled

Aircraft; this impressive title is a free translation of the French

wording on the cover of the official booklet handed out to all who

arrived at the French island of Corsica on June 21, ready for what

proved to be the largest of the five RC World Championships held

so far. A large majority of those attending the affair spent the

night of June 20 at the French seaport resort of Nice; around noon

Wednesday all hands gathered at a central point for a reception

tendered by the mayor, then piled into buses for a trip to the Nice

airport. Reception, bussing and the airlift to Corsica were part

of the "package" arranged by the Championships organizers, which

also included the five day stay in Corsica, board and lodging and

transportation back to Nice on June 27th. This competition

had its ups and downs. On the "up" side was a full week of perfect

flying weather - warm to hot days (on Sunday, the early morning

"heat reminded us of the Nats at Dallas!), cool nights, generally

low winds. Worst of the "downs" was serious interference on Friday,

June 23rd, first day of official flying: this was, in fact, the

first such interference which has ever been experienced at an RC

Championships - more on this later. Upon arriving at the

very modern Campo dell-Oro airport of Ajaccio, Corsica, a first

impression was of the fine climate (especially appreciated by many

travelers from parts of the U.S. who had experienced a cold and

wet spring - which had also afflicted England and much of Europe).

Next we were awed by the mountainous terrain, some of the higher

peaks of which appeared to carry remains of winter snow! The airlift

from Nice was via two planes; one was a huge double-decker Breguet

937, a four propeller job with ample room for the many model cases

which had collected at Nice. The upper deck of this plane had seats

for many of the RCers, while others embarked on an Air France Caravelle

for a considerably faster and more luxurious trip. Information pouches

were handed out to all at Campo dell'Oro, after which buses carried

all hands to their lodgings. The vast majority had a trip of about

seven miles along a very narrow and winding road, terminating at

the "Marina-Viva," a large resort which in the States would be termed

a motel. Though a little early in the vacation season, there were

already a hundred or so persons at the Marina, to which were added

some 150 or so RC flyers, officials and supporters. The latter category

includes those from any country who have no direct connection with

the meet, but just a love of flying and a desire to root for the

"home team" - wherever home might be. Even though interference

caused considerable delays, however, it was found possible to finish

the first official round of flying on Friday, June 23, not long

after 6 p.m.; start of flying was therefore postponed till 8 a.m.

on June 24th and 25th. While there is little model plane

activity on Ajaccio, there is a very active flying club; the attractive

headquarters building of the Aero Club de la Corse was a mecca for

all participants during the meet, and one of the two club hangars

was the main pit and storage area for planes. U.S. Team

members had no problem getting their large model boxes to Frankfurt

- terminus of the over-Atlantic airlift arranged through AMA. But

here problems arose; Wierick and Spreng found that no planes going

to Nice had room enough to carry the model boxes! (Kraft had shipped

his box directly from California to Ajaccio - which was fine, except

for the fact the box arrived at the airport at the last moment,

and just in time for the practice flying on June 22!). Through intercession

of various airline officials, the two flyers were allowed to take

their two planes apiece onto the aircraft sans boxes, a most unusual

concession. Incidentally, while checking their boxes at Kennedy

Airport in New York the boys had proof that RC modelers are literally

everywhere; printed on a corner of one box was a message saying

"Win the World Championships with these models, then give 'em to

us" and signed the L.I.D.S.- a prominent club that evidently covers

Long Island like a blanket! Due to uncertain transportation

between the Marina and the flying field, many entrants, including

the U.S. team, rented their own cars. Upon arrival at the Marina,

it was found that the management had banned battery charging! Doubtless

completely unfamiliar with model planes, the manager probably envisioned

a heavy-duty auto battery charger running in most every room, to

put a heavy drain on his meager voltage supply. It's likely a lot

of "bootleg" charging went on that first night! There were ample

charging facilities at the work hangar, of course. As is

usual practice at such meets, a full day of practice was allowed,

June 22. and each member of the 17 teams present got approximately

15 minutes for test flying; 43 pilots started the meet. In a determined

effort to come out on top, the German Team had arrived at Ajaccio

some days earlier, and were doubtless very familiar with the field

and the flying conditions by the time the meet started. Fortunately,

they had brought with them a most complete monitoring system to

check for interference. The setup even included an oscilloscope

for observing incoming signals, and a tape machine for recording

same, if desired. All this equipment was in a small station wagon,

but was used only on and off during the Thursday practice day. It

turned out that this was the only monitoring equipment at the meet;

apparatus which had been requested from the French government failed

to arrive in time for the meet (as did some other essentials, such

as meal tickets!). Since there is no real contest pressure

during practice day, Press photogs try to take as many photos as

possible then. This led to the hassle that seems to come early in

every World Champs (and usually at every U.S. Nationals tool), and

soon the Press representatives found themselves confined some 100

yards or more from the flying spot - an impossible situation. As

is usually the case this misunderstanding was eventually resolved

to the satisfaction of all - but why can't these things be anticipated

beforehand and suitable arrangements made before many hard feelings

are generated? During practice it was feared that many teams

would not have sufficient fuel to get through the meet. Our own

team had plenty, and Manager Jerry Nelson offered to supply anyone

who ran short - a gesture that was most appreciated. During

practice day we had a good chance to look over planes and equipment,

as well as to assess the level of competition. It was apparent that

this was to be a "proportional Championships," for our data showed

that every entrant flew propo in the meet (some may have had reeds

in their second planes, of which there are not complete records).

Out of 41 flyers, 19 used U.S. equipment of various makes, Bonner

Digimite being most numerous with six users. The German Simprop

system was most numerous in the meet, with ten users. Multi propo

equipment is no longer made in South Africa, and this team used

U.S. apparatus throughout. Digital apparatus is now made in France

(Radio Pilote, being marketed by 2nd place Marrot), and in Sweden

(Micronic - used in Corsica by at least one Swedish team member).

Though there is quite a variety of English propo equipment, all

British team members used U.S. equipment; this team was 100% reeds

at the last World Champs. Not many other flyers had planes

as small as the U.S. team - and many were far larger. There were

several copies of Fritz Bosch's Super Delphin, a really big plane.

Just about every plane was a low winger, except for the Satanus

II of Marrot, and a similar model by his teammate Cousson; these

are shoulder wingers with rather thick airfoil, and Marrot's well-deserved

second place testifies to their flying prowess, at least in the

FAI pattern. As a holdover from the 1965 Championships, there were

a couple of Brooke Crusaders - one modified with a swept wing.

The U.S. Team flew more or less new planes - much different

from those flown in the Eliminations last fall. Winner Phil Kraft

flew a version of his Qwick-Fli, which in fact, sported a three-year-old

wing, but this Mk III model had an upright engine, lower thrust

line, deeper rear fuselage and much larger rudder area than the

Qwick-Fli II. Power was an Enya 60 II, and radio equipment-well,

what do you think!? Fourth place man Doug Spreng had a rather small

taper-wing plane he calls Twister, powered by ST 60, while 10th-placer

Cliff Weirick flew the scale Chipmunk with Veco 61. The latter attracted

a great amount of attention due to its sleek scale appearance. Cliff

used flaps to slow down landing approach and used interesting take-off

technique with only partially open throttle, then opened right up

immediately after the machine broke ground. This helped the model

from nosing over. Engines were just about 100 percent 60-61

(one Fox 59 listed). We counted 11 each of Rossi and ST 60's, and

eight Mercos as the most popular. Many engines were fitted with

mufflers; several countries have mandatory muffler rules, among

them Sweden. However, the Swedish flyers operate in a much cooler

atmosphere and had some overheating troubles in Corsica. Engine

troubles plagued many other entrants as well; in this "sudden-death"

sort of competition (where every single flight counts, and one poor

flight for any reason at all can drop a flyer far down in the standings,

and can cost his team a top place) reliable power is every bit as

important as reliable radio. We noted that a good many competitors

were using the Kavan carburetor, which is gaining quite a reputation

in the U.S. too. The judge rotation system was the same

as inaugurated at Sweden; six judges (plus several alternates in

case of illness, etc.) were kept on duty, with four judging every

flight. After any group of four had judged four flights. two dropped

out and the other two took their places. Overall, this meant that

a judge was generally working for eight flights and off for four.

Order of flying was switched each day too, though the same basic

order was retained for the three official flying days. Thus, on

Friday, flying started with Tonnessen of Norway first; Saturday,

Tonnessen dropped to 20th, and the bottom 19 fivers on the Friday

list were brought to the top. Sunday another such shift was made,

resulting in Kraft flying first. This system worked fine. though

the word soon went out as to which judges were considered "tough"

and vice-versa! But it assured that no fiver would get the same

set of judges twice during the meet. The only real problem was that

when a flyer had a "delay" (which entitled him to a second try at

the end of the round), the same set of judges had to be assembled

as were on duty when he had his original try.

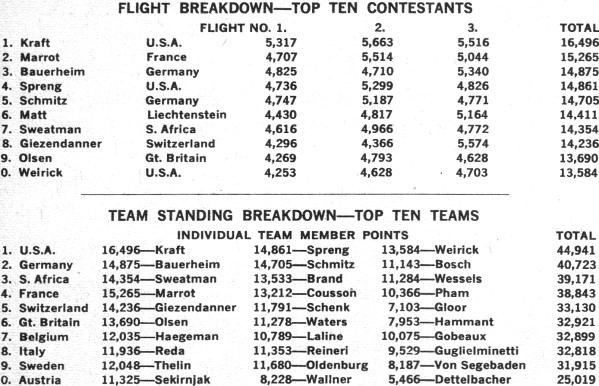

5th R/C World Championships Score Card

The judges came from the U.S. (Maynard Hill), Belgium, West

Germany, Great Britain, Czechoslovakia and France, and are appointed

by the CIAM, the modeling division of the FAI. Similarly selected

were the three jury members, with Walt Good from the U.S., A. Roussel

from Belgium, and Henry J. Nicholls from Great Britain.

Interference raised its ugly head early on Friday, on the flight

of Fritz Bosch, who was second man up. He had gone through eight

minutes of his pattern when it became evident he was in trouble;

he was able to land safely and the German monitoring setup, mentioned

earlier, detected strong interference very close to 26.995 on which

he was flying. The signals evidently came from a long distance,

as they would fade in and out; but when "in," the level was very

high. During the day, the interference would at times register a

stronger signal on the monitor receiver than would the RC transmitter

on the flight line only 150 feet away! All sorts of signals were

picked up -voice, code and so on. Unfortunately, the voices could

never be identified, but it would have mattered little if they could

have been: they doubtless came from much too far away to just call

the interfering station on the phone and ask them to please sign

off so the model meet could continue! This is the first World Championships

which has had any real interference trouble; it is likely to be

even worse two years hence in Germany, since the sunspot cycle will

be at its peak then - and high sunspot activity is what causes worldwide

problems from "skip" signals bouncing off upper atmosphere layers.

But what can you do? As the day wore on, the interference

faded considerably, so that by late afternoon it was not a problem.

Some contestants had been able to fly in their assigned position

in the lineup by shifting to less-bothered RC spots. Others could

not do so for various reasons (some just didn't have the necessary

crystals to do so) and were dropped to the end of the round, when

they flew late Friday afternoon. The fact that the monitoring

equipment was of German origin-and in fact, had been brought to

the field by a German propo maker (Simprop ) - posed some delicate

problems in international relationships. The jury finally solved

this and soothed all ruffled feelings by permanently posting one

of their number (Walt Good) at the monitor. All day Friday, every

transmitter was checked for exact frequency as soon as it was brought

from the Impound tent to the field. It was then switched off, and

the frequency checked. If no serious interference was detected,

a green flag went up, and the contestant could feel safe to fly.

If there was interference on the frequency, Juryman Good recorded

the fact, and made a record of frequency, signal strength, time

and other data at the moment on the tape recorder. With a red flag

up, denoting interference. a modeler was free to decide if he wanted

to take a chance or not (if he did, and got into trouble, he would

not be given a delayed flight). It's a tribute to the monitor

equipment and its operator that not a single crash occurred despite

the heavy interference - though there were several Friday caused

by the usual problems - equipment and pilot trouble. There were

several more crashes on Saturday and Sunday from the same causes,

in heavy contrast to Sweden, when not a single plane crashed during

official flying. A modeler can enter an official protest

to the jury at any time during the meet, of course; during all the

worry over interference on Friday, one experienced flyer felt he

was having unexplained engine speed changes during his flight, even

though no interference could be noted on the monitor. This fact

was taped by Juryman Good, who accepted the protest and the mandatory

payment of ten Swiss francs (about $2.50). It was later reported

that the flyer had changed his throttle servo - and had no further

problems in this line. With the interference dropping rapidly

Friday afternoon, some contestants elected to fly on the most troubled

spots, with no real problems. When it came time for Bosch to take

his delayed flight, all flyers were watching intently, as he could

very well have won the meet. But it was soon apparent that his engine

was sagging badly, and it soon quit during a maneuver! (Later examination

showed a speck of dirt in his fuel line.) It's useless to speculate

"what might have been"; but Bosch got only 810 points for his very

short delayed flight on Friday. His other two flights were well

over 5100 points each; "if" he had scored in the same vicinity on

the ill-fated first day, the German team might well have placed

first. A few hundred more points could have won first place for

him (provided our boys weren't inspired to do ever better than they

did). Unlike 1965, where there was a seesaw battle for first

over the three days of official flying, Kraft jumped to first place

on Friday and was never topped thereafter; he hit 5317, his lowest

score of the three days. He was followed by German flyers Bauerheim

(a veteran of World Championship RC flying) and Schmitz, the latter

a newcomer. Then came Spreng at 5th and Marrot at 6th. Cliff Weirick

was down at 12th. There were some surprises in this round; the South

African team looked very good, with flyers at 6th, 7th and 17th.

And the lone representative from Liechtenstein (first time this

tiny country has entered the World Champs) was a strong 8th in the

field of 42; Wolfgang Matt is only 19, flew a copy of Bosch's Super

Delphin which was only about 2 oz. under the maximum FAI weight

limit! And at that, he lost his landing points for being overtime.

Everyone expected the worst from interference on Saturday

- and there was practically none at all, nor was there on Sunday.

No one could explain why it had vanished so suddenly, as it was

apparent the Friday trouble was caused by a number of stations,

not just one; but that's the way the upper atmosphere often behaves,

as any ham radio operator can tell you. But while there was no interference

from long distance signals, there was some right on the field, as

it finally turned out. The air had seemed clear when Greek entrant

Papaspyros (1967 also was the first year for this country in RC

World Championship competition) was ready to fly late in the afternoon.

But some time after he became airborne, it appeared that he was

having trouble, and the monitor operator called attention to a whistle

that could be heard weakly under the strong sigs from the nearby

Greek transmitter. The red flag was run up immediately, and Papaspyros

was able to get his plane on the ground intact. With his transmitter

off. a rather potent and steady signal could be heard, obviously

a digital transmitter. An immediate search was started for one with

a switch left on. It was finally found - one of two identical transmitters

of flyer Cousson, both on 27.095 - the same as Papaspyros. One other

flyer had been up with no problems between Cousson and Papaspyros,

but on 27.255, so the switched-on transmitter hadn't been noticed

- if it was on at that point. Why wasn't it detected before the

Greek flyer took off? No one can say - but again an alert monitor

operator caught the interfering whistle in time to prevent a possible

crash. By the end of Saturday flying, it became fairly ,evident

how the top places would go - provided the holders of same fared

well on Sunday. Kraft led 2nd placer Marrot (on the basis of two

days scores) by some 700 points, but could still be deposed on Sunday

by the competent French flyer. Spreng was up to 3rd, Bauerheim had

dropped to 6th. Matt still clung to 8th place, while Weirick had

risen to 9th. France and South Africa still looked good in team

placings after U.S. Team Manager Jerry Nelson's charges, with Germany

now in 4th, due to Bosch's strong second flight, and his jump from

40th to 30th place.

Sunday

gave promise of extreme heat, and the early morning was practically

windless. Fortunately, a breeze came along in mid-morning which

made things .bearable (about 10 mph with gusts as high as 18). This

last day of the meet brought some surprises. For one, Swiss entrant

Giezendanner hit the highest score of the meet, with 5574 (Kraft

dropped a little, got 5516 on Sunday). The German, Bauerheim, made

his best score of the meet - 5340, and Bosch hit 5139. Matt placed

4th for the day with 5164, while Spreng and Weirick dropped a few

places. The top individual scorers for the three days were thus

Kraft 1st (16,496); Marrot, 2nd (15,265); Bauerheim, 3rd (14,875);

Spreng, 4th (14,861); Schmitz 5th, (14,705). Cliff Weirick ended

up in 10th with 13,584. Of the Team scores, the U.S. totaled

44,941 for top place; West Germany was 2nd with 40,723, South Africa

was 3rd with 39,171, France was 4th with 38,843 and Switzerland

5th at 33,130. It was generally felt that the organization

of the meet was extremely good, and the flying site and hangar areas

were certainly fine. The French had set up an unusual system to

record plane dimensions; each plane, after it had been weighed,

was suspended - nose downward over a lined backboard and photographed.

Thus a visual record was kept of wing area and other pertinent dimensions.

Spectator control on the field was strict, with Gendarmes guarding

the only entry gate to the flying site. The organizers had set up

bleachers and considerable lengths of fencing to keep spectators

back a safe distance. Surprisingly, very few spectators showed up.

Perhaps the other attractions of the resort area proved stronger

(like, miles of fine beaches, bikinis a dime a dozen, etc. etc.!).

Anyway, there certainly was no "spectator problem" - but

at the same time, the meet organizers failed to collect apparently

expected admissions to swell their sadly depleted funds. Scores

were posted on the master board in the main hangar amazingly rapidly;

lists of the days winners were passed out each night during the

evening meal, and on Friday, we even had a score listing of those

who had flown up until noontime. Trophies have usually been

awarded at the Victory Banquet, following these Championship meets,

but again, something new was tried in Corsica, an open air awards

ceremony conducted in front of the Aero Club of Corsica headquarters

building. There we found a small platform of three different heights,

the highest level in the center. As the top three individual winners

were called, they mounted the platform at levels befitting their

winning places, in the same manner as we see Olympic winners awarded.

As top winner Kraft took his place on the center of the

platform, the U.S. national anthem was played as the U.S. flag was

slowly raised on a central flag pole behind him. French and German

flags were raised as the second and third place winners came to

their platform spots. Then the 4th and 5th place winners, and team

managers of the top three teams were called. Prizes in the form

of trophies and merchandise were handed to all the top winners as

they came forward, various of the assembled dignitaries assembled

near the raised platform making the awards personally. All in all

it was a very impressive ceremony, marred only slightly by the fact

that it took quite a while to assemble everyone, and darkness was

approaching rapidly near the end. With the prizes awarded,

there was not much left to do but eat at the victory banquet, held

about 9 p.m. at the Marina-Viva. This banquet was in sharp contrast

to the very formal affair at Kenley in 1962, and the exuberant but

restrained affair at Sweden in 1965. It seemed that about half those

present wanted to do nothing more than let off steam, and speeches

by a few officials were simply unheard, though accompanied by flying

pieces of' bread and other objects. The view of many was that this

banquet might well have been eliminated! The Championships

organizers had set up a "free day" Monday, during which those attending

could go sight-seeing, fly their planes at the field, etc. A reception

at noon was held by the Mayor in honor of the RCers, after which

buses took everyone to a nearby beach for a bounteous meal and a

swim in the Mediterranean. Also, the Aero Club of Corsica offered

flights in a two-place glider for only ten francs (about $2), which

seemed barely enough to pay for the fuel used by the tow plane.

Only a few availed themselves of this opportunity, among whom was

this writer, who enjoyed it greatly. If there were any weaknesses

in the organization, it could be said they were in "communication"

and transportation. While all printed bulletins released during

the meet were in both French and English, few English announcements

were made at the field. Probably half those attending the meet did

not understand French, thus many were left in the dark as to what

was going on. As for transportation, since the living quarters were

quite far from the field, many felt that more frequent bus service

during the day would have been most helpful. If you missed the last

bus in the morning (which usually left the Marina about 9 a.m.,

you were on your own - and it was a long walk (or swim) to the field!

As a result, large numbers of modelers and others felt the necessity

of renting cars. Included in the "package" of housing and

transportation, was transport back to Nice by air. We understand

that Air France covered much of the expense of the Nice-Ajaccio

transportation, as well as collecting the French team members and

some of the French officials, and getting them to the island and

back home. The Belgians were carried from their country to Corsica

and back by Belgian military plane, while the Italians had similar

military transport from their armed services. The AMA was able to

pay or arrange for most of the expenses of the U.S. Team all the

way from California to Nice, where the Championships transportation

took over (and, of course, the $40 fee covering each meet entry);

much of the cost of this was covered by donations to the AMA RC

World Championships fund - yes, your donations really do count!

In closing, we find it impossible to thank individually

all those who labored mightily to make this a most successful 5th

RC World Championships, so will simply direct congratulations to

Mr. J. Ganier (Director of the French aeromodelling association

- the "French John Worth") and to Dr. M. Antonetti, Vice Pres. of

the Aero Club of Corsica, who handled much of the work on the Island.

May all future Championships be as successful as the 5th!

Posted April 21, 2013

|