February 1963 Popular Electronics

[ Table of Contents] People

old and young enjoy waxing nostalgic about and learning some of the history of early

electronics. Popular Electronics was published from October 1954 through April 1985.

As time permits, I will be glad to scan articles for you. All copyrights

(if any) are hereby acknowledged.

1963 was five years since

America's first communications satellite, Echo, was placed in orbit. Echo was a

passive, spherical reflector that merely provided a good reflective surface for

bouncing radio signals off of. By 1963, when this "Eavesdropping on Satellites"

article appeared in Popular Electronics magazine, the space race was well underway and active

communications satellites were being launched at a rapid pace. Spotting and tracking

satellites has long been a popular pastime with two types of hobbyists: amateur

astronomers using telescopes and binoculars, and amateur radio operators using antennas

and receivers.

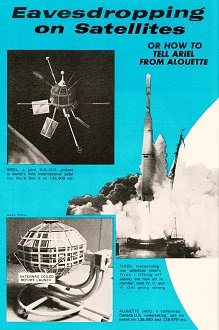

Eavesdropping on Satellites

By Tom Lamb, K8ERB By Tom Lamb, K8ERB

With at least six easy-to-snag NASA satellites

in the 136-137 mc. band, there's no time like right now to start pulling them in.

How? Well, a receiver offers no real problem-your present communications set can

be made to tune the 136-mc. band simply by adding a converter. And, you can either

modify an existing converter designed to cover the 2-meter ham band, or, better

yet, you can build the special "NASA 136" for this very purpose (for full details,

see the June 1962 issue of POPULAR ELECTRONICS, p. 39).

Fortunately, too, a large and elaborate antenna system is NOT necessary at these

frequencies. In fact, near overhead passes can be picked up with a 3' 7" dipole,

and you may even get satisfactory results with a TV antenna.

Start by listening for the Tiros satellites, since their signals are moderately

strong. With your antenna pointed SE or SW (in the U.S.), set your receiver for

c.w. reception, use a medium i.f. selectivity, and tune to 136.230 mc.

If your converter and receiver calibration aren't spot on, tune around the satellite's

frequency every five minutes or so, listening carefully for a weak carrier. An accurate

receiver can be left on the frequency until the carrier appears, although it could

take up to 12 hours for you to hear the first pass. A single, low-orbit satellite

can be heard for up to seven successive passes, followed by a 12-hour quiet period;

the exact sequence will depend to some extent on your location and system sensitivity.

Once you pick up the carrier, change to a narrow i.f., use a Q-multiplier, or try

any of the other tricks you may have for receiving very weak signals.

Identifying Satellites. All NASA satellites transmit a carrier (beacon) for tracking

purposes, and it's relatively easy to tell when you've picked one up:

(1) It will be accurately on frequency, but-

(2) A satellite will appear to be slightly high in frequency when approaching,

slightly low when receding. This Doppler effect will vary from nearly zero for a

distant pass to about 7 kc. for an over-head pass, and it's one sure way to identify

a satellite.

(3) Low-orbit (750-mile or so) satellites will be heard for only about 18 minutes

during each pass-usually considerably less.

(4) A satellite will usually be heard for several successive passes. (Since both

Tiros V and Tiros VI are on the same frequency, they confuse the picture somewhat-but

their transmissions will still be separated by the orbit period.)

(5) Most satellites are modulated by telemetry equipment. This modulation may

be quite weak, and audible only on near overhead passes.

Now that you know how and where to listen, you'll also want to know what satellites

to listen for. There are at least six, as we mentioned, of which the Tiros group

are especially good bets. Here they are, listed in order of ascending frequency.

Telstar

Frequency, 136.050 mc.; period, 157.7 minutes; altitude,

590-3500 miles. Telemetry on several very weak subcarriers. Long period and high

altitude make Telstar difficult to catch .

Tiros IV, V, VI

Frequencies, (IV) 136.230 and 136.920 mc., (V and VI) 136.235 and 136.922

mc.; period, (IV and V) 100.5 minutes, (VI) 98.7 minutes; altitude, 420-520 miles. Telemetry on weak subcarriers 1 kc. above and

below carrier. Tiros satellites are moderately strong and pass frequently. Weather

map pictures are transmitted on a higher band.

Ariel

Frequency, 136.408 mc.; period, 100.8 minutes; altitude,

247-750 miles. Telemetry sounds like clanking chains, out to ±15 kc. Ariel's modulation

is keyed from the ground and is not always present. Ariel is believed to have suffered

major solar cell damage from radiation belts and is transmitting erratically.

Alouette

Frequencies, 136.590 and 136.979 mc.; period, 105.5

minutes; altitude, 600 miles. Telemetry on multitone subcarriers out to ±20 kc.

A wide assortment of beeps and clanks makes Alouette one of the most interesting

satellites to log.

Other satellites in the NASA band are probably commanded from the ground and

are very elusive. But get Alouette, Ariel, Telstar, and Tiros (IV, V, and VI!) in

your log before you start think-ing about snatching any of the hard ones!

|