|

Way back in 1975, my friend, Jerry Flynn,

and I (Kirt Blattenberger) assisted Mr. Dick

Weber in his successful flight on June 14, 1975, that set a new FAI Closed Course

Record of 225 miles in 5 hours and 38 minutes. We were both flaggers to signal when

the Tortoise has passed the distance markers. See the credits on page 37 in the

actual magazine. The Tortoise got its name by virtue of the craft having landed

near a turtle on the runway. It was a long day, with everyone being sunburned by

the end of it. We were all members of the Prince Georges Radio Control Club (PGRC).

Note: This article on the

Tortoise was previously posted with the magazine pages in image format. Now,

this version has been OCR'ed (optical character recognition) so that all of the

text is searchable.

652 Miles Per Gallon!

After setting the record, the designer displays the airplane

and complete support system. Size of the ship is only slightly larger than pattern

jobs. Covering is transparent Super MonoKote. Wing is half blue and half yellow,

colors which show up best against any sky background.

Richard R. Weber

Setting a new FAI Closed Course Record of 225 miles in 5 hours and 38

minutes, the Tortoise landed with 55% of its fuel still in the tanks.

In the autumn of 1973 I decided to go after FAI distance and duration records.

I had completed a satisfying summer of pylon racing, but there were not enough Quarter

Midget races in my area. World records offered a new challenge.

The first order of business was to find an engine that would run economically,

so engine tests were initiated. From the outset I intended to use a diesel engine

because it runs longer than glow, without the complication and interference of ignition.

However, most of the engines tested were glow, since they were available. An engine

that runs economically on glow fuel should be even better as a diesel. Articles

were found on records set by Bertrand, Giertz, Hill, Hirota, Kaiser, Reed and later

Giertz. The engines they used ranged from .15 to .49 cu. in. displacement. After

many hours of running about 20 different engines, I chose a Supertigre 29 RV. One

of the reasons for this choice was that since the same basic crankcase is used up

to a .46, it seemed that it should be strong enough to convert to a diesel.

Next it was time to bone up on aerodynamics. I gathered many books and articles

on the subject. Perhaps the most useful book found was Man Powered Flight by Keith

Sherwin. The problems it considers are quite similar to those encountered in distance

or duration models, viz., designing to fly with minimum power. Another valuable

book for the dedicated modeler is Fluid-Dynamic Drag by S. F. Hoerner, which contains

the results of a great many airplane drag experiments relevant to model design.

A third source of information deserving more attention than we give it is the collection

of NACA annual reports from the 1920's and 1930's.

There are three record categories stressing fuel economy: Duration, Closed Course

Distance, and Straight Line Distance. Closed course distance was chosen first because

it requires a smaller plane than Duration and is a much easier undertaking than

driving several hundred miles (and back) for Straight Line Distance. The Straight

Line Distance record also requires more reliability, because the landing point must

be specified within 500 meters before take-off.

Preparing for the flight the author is engrossed with the plumbing.

Tanks. two 48-oz. plastic detergent bottles extend 3 in. in front of wing to 5 in.

behind. Radio is midway between the wing and stab with hatch on top of fuse.

A hefty shove is an important take-off assist. On record flight

the run was about 600 feet. Plane weighs 5 1/2 lbs. without fuel, 10 1/2 loaded.

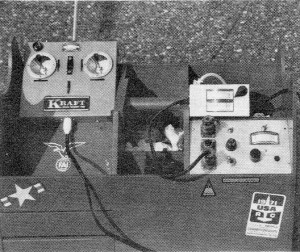

Radio was Kraft 6-channel with two-third brick in airplane. Engine

was Super Tigre R/C .15 Diesel conversion. Glow case proved inadequate for sustained

Diesel running.

Close up of the special field box containing the interlace equipment

described in article. A compact arrangement.

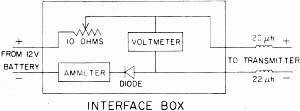

Transmitter battery supply schematic.

Result of ground loop ending in grass was snapped fuselage. Repairs

took only a half hour. Controls were elevator. rudder and needle valve: Pressure

fuel system was used with homemade regulator between tanks and needle valve. Four

C cell NiCads supplied airborne radio. Transmitter pack good for only four or five

hours. Interface box permitted simultaneous charging of batteries, power to X-mitter.

Fuel system configuration schematic.

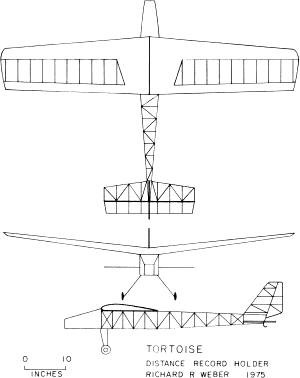

Tortoise airframe details.

The airplane went through numerous design stages, keeping in mind the FAI limitations.

These include a maximum weight of 11.02 pounds, maximum flying surface loading (wing

and horizontal tail) of 24.57 ounces per square foot, and maximum engine displacement

of .61 in3. Early sketches were beautifully streamlined, but by the time

construction began the design had become rather simple, not unlike its record-setting

predecessors. Its chief features are the tapered wing with a genuine Clark Y airfoil,

and a built-up fuselage with no formers or cross braces.

The fuselage is filled from firewall to tail with fuel and radio components.

There are two fuel tanks, made from 48 oz. plastic detergent bottles, extending

from 3" in front of the wing to 5" behind. A hatch between the wing and stabilizer

provides access to the radio. The model is covered with transparent Super MonoKote.

To assist visibility under various sky conditions one wing panel is dark blue and

the other is yellow. Experience has shown that one color or the other is easily

seen against any sky background. The complete airplane weighs 5 1/2 pounds without

fuel and nearly 10½ pounds fully fueled.

The radio control system had to be reliable, compact, and easy on the battery.

A check of the current drain of several systems indicated that the Kraft 3-channel

brick would be ideal. I obtained a brick which was then converted to my transmitter

frequency of 53.2 MHz. Some additional work by Doug Spreng of Kraft Systems reduced

the servo current drain further. I planned to use rudder and elevator controls,

but the third channel would be available for engine control if needed.

The batteries for the airborne radio system were four C cell NiCads, rated at

1.5 AH and found to exceed 2 AH. The NiCad transmitter battery pack is good for

only four or five hours, so I made an interface box to charge the transmitter batteries

and power the transmitter simultaneously. It contains meters to monitor the current

and voltage supplied to the transmitter. It also has a potentiometer to vary the

current. This interface box connects the transmitter to the battery in my field

box or to a car battery. It was used about half the time during the record flight.

During the summer of 1974 I flew RC planes with diesel engines in order to become

familiar with their characteristics. I would like to encourage much wider use of

diesels. Contrary to popular belief, diesels start easily and they can be throttled

down like the best glow engines. Perhaps my most notable flight of 1974 was on September

2 with a heavy Box Fly Jr. powered by a Supertigre 15 R/C diesel. It took off the

ground and flew with the engine running for 1 hour and 45 minutes on four ounces

of fuel.

Initial flight tests on the new record model began on December 23, 1974. A fuel

cutoff was connected to the third servo for ending test hops. I tried a variety

of likely propellers with the plane carrying two pounds of water and 11 ounces of

fuel. Surprisingly little difference in air speed was found between the different

test props. The final choice was a Power Prop 11-7½, just like on your big pattern

ship. Later flights gradually increased the fuel load, to ascertain whether the

shifting CG and increased weight would present any problems; generally they did

not.

The fuel system consisted of two pressurized plastic tanks connected in series,

followed by a fuel pressure regulator. Tests were all satisfactory, although a problem

developed later.

On May 10, 1975, we gathered for an official attempt on the FAI Closed Course

Distance record, sponsored by the Prince Georges RC Club and the Goddard MAC.

Present were John Sites, CD, Luther Jackson, Eric Baugher, Ken Greenhouse, Ron

Moltz and Chet Opal. I estimated the chance of success at 50-50, since we knew of

no problems but the plane had never been flown longer than 75 minutes. It was not

a propitious day. At take-off the 10- plus-pound airplane ground looped and went

into the grass beside the runway. The fuselage broke in half behind the wing. A

brief discussion ensued and Ron Moltz was off to his home for some Hot Stuff and

sticky MonoKote. To my amazement the plane was repaired and flying half an hour

after he returned. The official flight was only fifteen minutes old when the engine

went lean and slowed down. Then it repeatedly improved and went lean in random fashion.

We worried about it when it was very lean, but it kept on running. Lap times, which

had been running 52-54 seconds in the beginning, soared to over 70 seconds, but

still it ran. After an hour of this I had just decided to stop worrying, convinced

that it would continue to torment us all day long, when the engine stopped suddenly

after 73 laps.

When the plane landed we found that the rear engine bearing had pushed out the

bottom of the crankcase. We theorized about several possible causes of the problem:

faulty regulator, lean needle-valve setting causing overheating and deposits on

the piston crown, which raised the compression too high, or fatigue from detonation

during earlier bench testing of the engine. The possible problems were all rectified.

The regulator was reworked, the needle valve was hooked up to servo control and

a brand new crankcase was found.

The second attempt on the record was on June 14, 1975. The officials were Luther

Jackson, CD, Dean Smith, Chet Opal, Eric Baugher, John Tallman, Jerry Flynn, and

Kirt Blattenberger.

After one of the test flights to adjust the engine, the plane landed near a tortoise

walking on the runway. We immediately concluded that this was a good omen. Since

the plane was nameless, it was dubbed the Tortoise, for its slow but steady flight.

When the tanks were filled the ground looping of May reappeared, but the plane

took off on the fourth attempt, after a ground run of about 600 feet. The old record

was 338 laps (kilometers) around the course defined by two pylons 500 meters apart.

Since FAI records must be broken by 2%, our magic number was 345 laps. The flight

went without major problems. Occasionally the motor would go lean, but the new mixture

control took care of this. Sometimes when the motor sounded fine, I would set it

leaner to see if it would sag; usually it did and was immediately set richer again.

As we were nearing the record, at about lap 341, the engine went quite lean, but

the needle valve was quickly opened and each of us held his breath. When lap 345

was completed, there was a round of cheers, for the record was ours!

The engine then seemed happier, probably because we were not so concerned. Talk

of 400 and 500 laps began to sound reasonable, but it ended abruptly at the end

of lap 363, when the engine stopped without warning. The plane glided in to a smooth

landing at the center of the course. It had flown 363 kilometers (225 miles) in

5 hours and 38 minutes, averaging 40 mph.

Upon removing the wing we were overjoyed to see what looked like 75% of the fuel

remaining! There would be another day and a longer record for the Tortoise! Then

we noticed that a check valve in the pressure system had failed to allow air into

the tanks to replace the fuel removed, and the tanks were partially collapsed from

engine suction. A subsequent measurement showed that 55% of the fuel actually remained.

This works out to about 650 miles per gallon.

The problem which stopped the plane was found to be the same one we had in May:

the bottom of the crankcase broke under the main bearing. The reason for the problem

is now clear. The high-compression loads of diesel operation exceed those which

the crankcase can tolerate for extended periods of operation. If a stronger engine

can be found, and I believe it can, the plane should be capable of 500 miles on

a closed course and more on a straight line course. With a larger wing and lower

rpms, maybe it can exceed the present duration record of 14 1/2 hours set last year

by Lars Giertz of Houston.

An assault on world records cannot be made without the help of many people. My

greatest help came from Dean Smith, whose engineering expertise and machining abilities

were indispensible. Dean and I kicked around many ideas and went down our share

of dead ends before finding the right combination. Dean made the pressure regulator,

the parts for the diesel conversions, and many other parts used in the assorted

experiments we tried. I also benefitted from discussions with Don Jehlik and Cliff

Telford, both world champions and gentlemen.

Editor's Note: A straight-line distance RC performance record of approximately

266 miles was established by the author on August 16. The record is in the process

of being homologated by FAI. Take-off was at 9:31 a.m. from Newton, Kan. and the

landing took place at 4:49 p.m., at Enole, Nebr.

Posted November 2, 2021

(updated from original post on 3/23/2012)

|