|

If you have been in the modeling world

since at least the 1990s, you have witnessed the slow but steady evolution of electric

propulsion systems to the point where we are today with the technology having overcome

and largely replaced glow engines. During that time, the resentment and jealousy

of glow engine modelers has been very apparent. I must admit to having some feelings

of betrayal to the power source to which I owed my early days of model flight, but

by the early 2000s I was using electric power in my gliders - before brushless motors

and lithium-polymer batteries were household words. By 2005 or 2006, power-to-weight

ratios of brushless motors and LiPos were on par with and pushing past glow engines.

Now, with 40C batteries, incredibly powerful outrunner motors, and finely engineered

electronic controllers, there is no reason other than for nostalgic satisfaction

to not use electric power. The added benefit of no-hassle operation, no

messy oil, and no noise clinches the deal. Author Jack Headley could never have

imagined the state of the art less than half a century after his article.

The Sound of Things to Come: Electric Powered Model Planes

Electric Power Is Here Now.

Jack Headley

The Royal Aeronautical Society published

a series of papers under the general heading of "Looking Ahead in Aeronautics" during

the late 1960s. These papers authored by some of the world's experts in the aeronautical

art covered a wide range of topics regarding what aviation is going to be like in

the next hundred years. In one of the papers B. S. Shenstone discussed what's going

to happen to "Unconventional Flight" by which he meant gliders, sailing boats, man-powered

aircraft, and in addition model airplanes. This surprised and delighted me, as models

rarely make their appearance in "serious" literature. One sentence in particular

interested me: "The need for an entirely different source of power and fuel may

not be fully realized at present, but such a unit and the aerodynamics and structure

to match is bound to come." When I read this in 1968 I couldn't see why we would

need a new power source. What could be wrong with the old glow motor? The Royal Aeronautical Society published

a series of papers under the general heading of "Looking Ahead in Aeronautics" during

the late 1960s. These papers authored by some of the world's experts in the aeronautical

art covered a wide range of topics regarding what aviation is going to be like in

the next hundred years. In one of the papers B. S. Shenstone discussed what's going

to happen to "Unconventional Flight" by which he meant gliders, sailing boats, man-powered

aircraft, and in addition model airplanes. This surprised and delighted me, as models

rarely make their appearance in "serious" literature. One sentence in particular

interested me: "The need for an entirely different source of power and fuel may

not be fully realized at present, but such a unit and the aerodynamics and structure

to match is bound to come." When I read this in 1968 I couldn't see why we would

need a new power source. What could be wrong with the old glow motor?

Well, here it is 1972, and there are quite a few people ready to tell us what's

wrong with the old glow motor. For some reason the sound of a control-line model

buzzing around is greatly disturbing to the majority of the population, who are

otherwise deaf to lawnmower engines, helicopters, minibikes and the like. In short,

we produce too much "noise pollution."

How does this model specification fit Shenstone's requirements? (1) Different

source of power - electric motor. (2) Fuel - instantly rechargeable battery. (3)

New structure - foam wing and tail, plastic body. (4) Noise level - None (almost).

Does such a thing exist? Yes, in fact there

are two of them. One is an RC model, and the other is a free flight called the "Superstar,"

both now available from Mattel and both powered by electric motor units. Does such a thing exist? Yes, in fact there

are two of them. One is an RC model, and the other is a free flight called the "Superstar,"

both now available from Mattel and both powered by electric motor units.

We'll concentrate on these electric motor units, in particular the smaller one

from the "Superstar," but the suggestions will be applicable to both units. But

this shouldn't be looked on as just another motor type; it is actually a means of

bringing back flying from the outer boondocks to the local park, or even our own

backyard. In one stroke of genius one of the major drawbacks of modern aeromodeling,

the noise problem, has been eliminated. Thanks to Mr. Mattel, we are now able to

fly around the local neighborhood rather than drive for hours to find a place to

do a little free flighting.

Without too much divination, we can see the following immediate applications

for the electric motor power unit.

Scale Models

Nothing sounds less scale-like than a beautifully built scale model powered by

a small glow motor running at about 20,000 rpm. And nothing is more frustrating

than trying to start a small diesel motor that's fully cowled in a scale ship, so

here we have the perfect power unit for the scale model. Possibly the quietness

won't sound scale-like either, so we could add a little noisemaker to the engine

to correctly simulate the true sound!

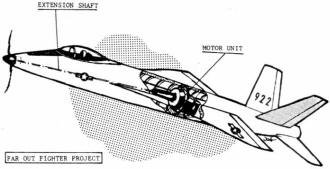

More seriously, other applications could be for long nosed models. Here it should

be relatively easy to replace the existing motor shaft with a longer one, thus keeping

the motor over the CG. Our sketch of the Far Out Fighter illustrates this idea.

For pusher models simply reverse the battery leads, put the prop on backwards,

and away you go.

Ducted Fans

What looks like a canopy is built up of balsa blocks and triangles.

Space inside will house battery packs.

Before carving and sanding, fuselages sure look ugly!

A Viper takes on smooth curves. Fit the engine to aid in shaping

the nose.

Vipers 1 and 3 differ in that the latter model has less dihedral.

Several have been made by very different builders; all perform the same.

Author with Toledo winnings. Dario still has not flown the original

plane - it is too pretty! The others fly all the time when Dario is not making helicopters

See the remarks about starting fully cowled engines in scale models and double

them for ducted fans. Here's the ideal application for the electric motor, just

switch it on and it runs. For this application the motor unit should be put in backwards,

and a "left-handed fan" will be required. The sketch shows a possible installation.

Auxiliary Power Unit for RC Gliders

Gliders can often be flown in populated areas, mainly because of their "noiselessness,"

and use of the conventional strap-on 049 motor for calm days is usually not too

practical, so why not an electric power pod - at least it won't bring all the neighbors

running. The sketch shows one possibility, a nose mount rather than the usual over-the-wing

system is preferred because of the prop diameter. But, no goop on the model and

no necessity to fuelproof same. Bigger batteries will also give more duration.

Multi-Engined Free Flight Models

By far the biggest problem in multi-enqined models is that of keeping all the

motors running evenly, and having them all stop at the same time. No longer. Run

all the motors from a common battery pack; switch on and all props are spinning,

the batteries run out and all the props stop at the same time - fabulous. Now for

less than $30 you could probably build a free flight B-17 and get more than one

flight out of it.

No need to sketch ideas here, they come too readily to mind. Now, with 12 motors

I could finally make that Dornier Do.X and then maybe that ...

And lots more, it doesn't take too long to think of all sorts of exciting applications.

You've probably thought of two or three others while reading all this. So let's

cash in on this fabulous possibility - it's not too expensive either. Our local

discount house sells the complete "Superstar" package (that's model plus motor)

for around $7, cheaper than most glow motors these days. So buy one or two and try

silent flying - it's fun.

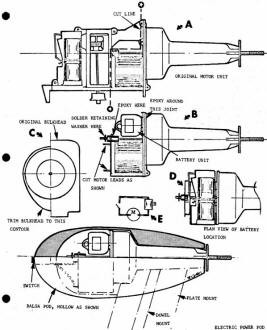

But just in case you haven't run across one of these motors yet, we've made a

sketch showing the various components. This is the standard unit, just as fitted

to the "Superstar." It doesn't take too much imagination to see that a much lighter

and more compact unit could be made.

Motor Unit Modifications

Probably the first item we can delete is the small gear box used with the cam

rudder control, and then after this, the batteries can be relocated, either above

the motor, or in a separate package, which means adding a couple of about 16-18

gauge connecting wires.

Another possibility is to increase the length of the motor run by adding a further

pair of batteries in parallel with the first set.

We've mentioned the extension shaft already for use with long nosed models, so

the opposite approach for stubby nosed models like the Sopwith Camel would be to

shorten the prop shaft. This would mean cutting the plastic support structure and

remaking the forward bearing, but this should be easily done.

In short, we can see that all types of modifications are possible and these can

be accomplished using only a few hand tools.

A final suggestion is to fit a freewheeling propeller. Any of the well-known

rubber model type freewheelers should work here. The one we prefer is the "one-way"

clutch type.

Model Sizes

So far we made two original electric models, plus another converted from a large

rubber scale model, and flying these plus the original "Superstar" has given us

a good first shot at sizing electric-powered airplanes. The two originals (both

called Vampires, although they were different designs) were around three-ft. wingspan,

which seems about optimum. These models had a good fast climb, followed by a reasonable

glide. The converted rubber model however, had almost no climb, with a ceiling of

about 10 to 15 ft., but this had a wingspan of just over four ft. So 36" to 40"

looks about right for the span, with not too heavy construction.

Concluding Remarks

Electric models are a lot of fun to fly, and in these days of instant everything,

give instant flight. Contest flying is undoubtedly not far away, and indeed as this

was being written we received word that the 1972 "Flightmasters" Annual Scale Contest

would have a class for electric-powered free flight scale. So why not try electric

flying, you'll like it.

As anyone who's done a little slope soaring knows, there are times when, after

hauling all the equipment to the top of the local lump, the wind, which has been

blowing steadily for days, ceases as soon as the model is assembled. Maybe Mother

Nature is upset because I eat too much margarine or something, but it does seem

to happen to me quite often. So what can we do about this? Up to now my solution

has been to sit around on the top of the hill complaining, but this doesn't get

much flying done, so I decided to make a power pod for just these occasions. So

what, you say, power pods have been around since Pontius was a pilot. Ho-ho, sez

I, but not my non-polluting, non-oily, silent electric type power pod. Made from

a Mattel free-flight model power unit, it's easily constructed and can be kept in

a corner of the model box for just those days. Want to make one? The following step

by step instructions show how to convert the Mattel unit into a Mother Nature beater.

Original and modified motor units.

On the "Capstan" test bed. On the "Capstan" test bed.

(1) Cut off the gear box-battery assembly from the motor unit (Fig. A).

(2) Cut the motor leads about 1/4" aft of the motor.

(3) Trim off the rear bearing to a small cylinder.

(4) Epoxy this bearing to the frame, and also run a bead of epoxy around the

front bell housing (Fig. B).

(5) Trim the bulkhead to an oval shape (Fig. C).

(6) Solder a retaining washer to the big gear shaft (Fig. B).

(7) Trim the battery carrier as shown (Fig. D), removing the slide switch in

the process. Affix the batteries to the carrier with masking tape.

(8) Solder a pair of wires to the battery, motor, and a new slide switch (Fig.

E).

(9) Make up the balsa pod and insert the motor. The pod is split horizontally

for this purpose and is held together with a couple of rubber bands.

(10) Pod mounting is optional, the sketch shows both a dowel type mount and a

plywood plate, so take you pick.

Charging the batteries is accomplished in the original way. The total weight

of the original pod plus motor unit came out to be three ounces.

Editor's Note: Several issues hence AAM will present a major article by Bob Meuser

in which he reviews the many electric power systems now being offered to modelers.

This will include technical data, information on weights, power duration, battery

requirements and charging systems.

Posted January 19, 2019

|