|

In the mid-1940s,

toward the end of World War II, Flying Aces magazine changed its name

to Flying Age, while changing its focus from model aviation to aviation

in general. Much to the consternation of many of its readers, that included no

longer including the much-loved fictional stories of flying superstars like

Kerry Keen (aka "the

Griffon"), Dick Knight

, Captain Philip Strange,

Battling Grogan

and his Dragon Squadron, Crash Carringer,

and of course Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham. The good aspect of the change is that

Flying Age published a lot of stories about full-size aircraft and flying which

were geared toward their audience of modelers who were interested in all aspects

of aeronautics. This piece discussed primarily variable pitch, constant speed

propellers being used on military, commercial, and civilian airplanes. You, like

I, though that by now there would be similar propellers available for model

aircraft use, but apart from a few homebuilts, no commercially made products are

available (there was one for indoor electrics, but nothing for powerful engines

/ motors). Given the number of variable-pitch rotor heads for helicopters, it

shouldn't be so hard to implement for airplane propellers.

Propellers

The great B-29 props, sixteen feet seven inches in diameter,

are the largest on any military airplane. Boeing Photo

Important as frame or engine is the prop, now developed to a high efficiency

and great complication.

The man who makes propellers is not always a happy man. When he hears or is told,

with business in mind, about a new airplane, his mind hurriedly skims his stock.

If he's one of the big prop boys, he may have seventy or more propeller designs;

if he's one of the smaller manufacturers, he may have only a few. But, somehow,

he has to fit the airplane to a propeller. Is it going to be single or dual rotation?

Shall it have three wide blades or four narrow blades? Will it be better with narrow

tips and wide shanks? How about using square tips?

Unless he's looking harshly at the jet-propulsion people, the propeller maker

is busily engrossed, therefore, in compromising with the engine maker and the airframe

maker. As long as airplanes are made in pieces and by long distance, that's going

to be true, The prop problem, consequently, is just as important to aviation as

the other two: what holds it up and what makes it go.

The propeller, of course, is the member of the plane-propulsion-prop combination

which has the job of delivering the maximum thrust horse-power possible from the

shaft of the engine. At the same time, it is an ungainly mechanism stuck out at

the end of the airplane. But it does give the aircraft forward thrust. So its positive

function far outweighs its negative values. It must, accordingly, be carefully designed,

absolutely functional and aerodynamically correct.

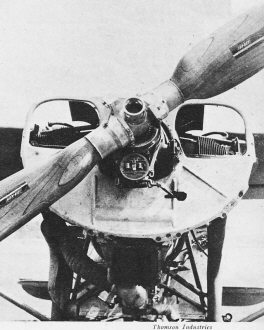

Fully-automatic, Curtiss electric propeller designed for bombers,

post-war transports. Curtiss-Wright Photo

Ten varieties of Curtiss electric props. Of hollow steel, they

were pre-designed for warplanes, then modified. Curtiss-Wright photo

Most used is this three-blade prop. More than four blades are

not efficient, though five are used abroad. Curtiss-Wright photo

This Curtiss pusher, flying in 1912, used a fixed-pitch wooden

prop with slight anxiety about its efficiency. Official U. S. Navy photo.

Diagram of a propeller shows its true airfoil construction. Note

how the airfoil changes as blade is constructed.

A DC-3 in flight with its left engine feathered. Full-feathering

props are required now on any multi-engine plane. When the engine is out during

flight, the prop acts only as drag. Pratt & Whitney Photo

An exploded view of the installation of the Aeroprop (GM), hydraulically-operated

constant-speed prop used on U.S. fighters.

The Iso-Rev, by Zimmer-Thomson Corp., is a constant-speed prop

designed for small planes. It operates (left) by using split pulleys and two drives,

one fixed and the other variable with the pulleys. Pitch change is effected when

there's a difference between the ratio of the two drives.

A V-belt is fastened to governor on nose.

When the Wright brothers were fussing around with heavier-than-air craft at the

beginning of the century, a propeller .problem was laughable, judged by the weightier

crisis of making the thing stay up in the air. But the Little World War, like its

far huskier offspring twenty years later, whizzed up aircraft research until, as

higher speeds, horsepowers and efficiencies were attained, designers began to worry

about the windmill laboriously pulling their aircraft through the air.

Fundamentally, the blade of the propeller is an airfoil with all its characteristics.

All you have to do is twirl the airfoil rapidly in a vertical position instead of

passing it through the air like a wing - and there's the blade airfoil. The pitch

of the propeller is, simply, the twist or angle of the blade to present the best

possible aerodynamic combination, or to get the best bite through the air. In the

old days, manufacturers almost always used laminated wood in a single piece bolted

to the engine nose. The same type, with modifications, of course, is still used

on small, private aircraft.

But as planes and their uses became larger and more varied, inventors and engineers

have labored - for the past. twenty-five years - to design a hoped-for perfect propeller

in which the pitch can be changed automatically by the natural forces to which any

propeller is subject when it's operating. In other words, the major goal has been

to make the propeller suit automatically changing conditions in the air.

Let's define the major types of propellers. The fixed pitch, as we've said, is

usually made in one piece from wood or dural and is quite light and simple. It's

designed for certain airplane and engine combinations to provide a set of selected,

compromised. flight conditions which can be obtained by the single, fixed angle

blades. Thus, if good take-off characteristics are the most important ones desired,

the propeller is designed to provide that one major feature, and cruise and top

speed are compromised in its favor.

Adjustable propellers are those which have a hub containing two or more blades

which may be adjusted when the plane is on the ground. The adjusting is done by

loosening the fastening of the blade and simply rotating them to a different angle.

This kind of propeller can be used in several different installations and provides

a way of getting a variety of performance characteristics. But in flight the adjustable

propeller acts exactly like a fixed-pitch prop and it can satisfactorily meet only

one condition at a time.

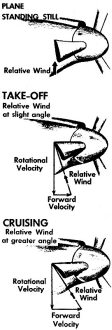

The diagrams (left) show how the pitch of a prop blade, affected under different

conditions by relative wind, is changed to get the best pitch conditions.

Controllable propellers cover a wide range of types. In general, any propeller

whose blades can be turned in flight at the pilot's direction is a controllable

type. Various features of controllables must be explained to qualify use of the

word when applied to a specific propeller.

The simple controllables are taken in hand by the pilot who manually changes

the angles of the blades through a linking or controls a mechanism which is powered,

handily enough, by the rotation of the propeller. But constant speed, feathering

and reversing propellers like those on large and very large aircraft (discussed

later) are controlled indirectly. The pilot sets a governing mechanism which takes

charge of the whole business by directing an auxiliary power source (electric or

oil pressure) to change the setting of the blade angle. The governor reflects changes

of engine speed and fixes the propeller around to get the very best performance

out of it without worrying the pilot.

The problem is, obviously, a simple one. It involves making the best, strongest

and lightest propeller. and then getting it to change its pitch, when necessary,

in the easiest way - preferably without bothering the pilot. But into it have gone

many years and many millions of dollars for research.

(Feathering, mentioned above, is now provided on practically all multi-engined

craft. It involves changing the pitch, or twisting the blades in the hub until they

lie in the direction of flight - or the width of the blade points in the same direction

as the airplane is going. In this position, the blade acts as a brake to stop the

engine's rotation, preventing further damage to the engine and preventing the vibration

that would result if the propeller continued to windmill. Drag is substantially

eliminated to the point where a multi-engine plane with one engine inoperative can

fly higher and faster with the propeller feathered. Large propellers capable of

being fully feathered have been in use in this country for more than five years.

And feathering will soon be available in several new types of props developed by

the AAF for powers under 500 hp.)

Of what materials are propellers made? Well - wood, of course. It's used on most

lightplanes. It's simple, light and inexpensive. Wood is not subject to failure

from fatigue, as are metals. No high-speed, high efficiency American aircraft uses

wood propellers. But the British during the war used a great deal of wood for their

fighter craft. They stubbornly maintain its efficiency. Most honest Englishmen will

now admit that their extensive use of wood propellers on combat planes was really

a war measure caused by the fact that they did not have enough forging capacity

to produce metal blades.

The best materials for blade construction are steel and duraluminum. Magnesium

props have been made, but, because they're less elastic than dural, they must be

thicker, which automatically makes them lose any weight advantage. The weight factor

is, naturally, tremendously important. That's why hollow blades are made. As sizes

increase, a point is finally reached at which the hollowed-out steel blade is equal

to the weight of a solid dural blade; with present blade designs, that's at about

thirteen inches. If it's to be wider, the blade section is so thick that it must

be hollow to have a reasonable weight.

That's not all the propeller maker has to worry him. His propeller has to suit

other considerations. What's the clearance of his propeller to be? And the clearance

factor is not only limited by the ground or water, but, in the case of a multi-engine

aircraft, by the closeness of one engine to another or to a structural part of the

plane. Is the installation to be tractor or pusher? If it's pusher, there's a big

problem raised with the turbulence caused by the air passing over the wing and flaps

into the propeller. That sets up an excitation or vibration. (The latter difficulty

may soon be overcome by proper design of the wing to reduce turbulence and closer

study of engine nacelle placement with regard to the areas of least turbulence on

the trailing edges.) What sort of job will the plane be asked to do? That's important

because it may even bear on the type of material to be used. During the war, for

example, many combat planes were operated from unimproved flying fields where the

propeller was subject to having stones and that sort of thing thrown up at it by

the landing or hose wheels. (Answer: hollow steel blades which are most resistant

to nicks.)

A controllable, reversible, hollow steel prop (1920) built by

Standard Steel and installed on engine of deH. biplane.

Then, when he has patted himself on the back for successfully completing an assignment,

the plane may be modified and upset all his calculations. That happened to Hamilton

Standard Propellers of United Aircraft, with its Mustang propellers. The P-51D was

nicely equipped with props having narrow tips and very wide shanks, all of which

provided better engine cooling, less compressibility effect and better performance

for that particular fighter. Then along came a new version, and the propeller had

to be changed into an item with square tips and a narrower shank.

He has to worry about the number of blades he's going to use. There has been

a trend (notably in the Rotols used on the Supermarine Spitfire) to use up to five

blades on a single propeller. Theoretically, the best propeller has an infinite

number of infinitely narrow blades. But the most important factor is the solidity

of the prop. The reason for the Spitfire's five blades is, simply, that with their

wooden blades and type of hub construction, they cannot use the wide blades used

in this country. To get the same degree of solidity, therefore, they have to add

blades. Thus, three wide blades with the same percentage of the total disk area

as five narrow blades result in just about the same performance, and they're a lot

cheaper and simpler. Many blades are really necessary only when the propeller operating

forces that result from the use of excessively wide blades are too great to be handled

practically.

Propellers used to be custom-built. With the tremendous quantities of planes

now in use and the .extreme variety of their uses, that's impossible now. The propeller

maker must try to anticipate every possible need of the aircraft and engine manufacturers

in advance. When they arrive with their specifications, he can select and refine

the most suitable prop he has in stock. And he knows how important it is, for, without

the right propeller, the airplane just isn't going to do its best job.

Posted May 1, 2023

|