|

According to this article from a 1962 edition of American Modeler, the U.S. Air Force had a great policy for its

overseas bases whereby it made sure that, where possible, airmen interested in engaging in just about any form of

hobby activity had supplies and facilities available. Everything from a well-stocked hobby shop to building and

flying facilities were provided on base, and often nationals from the host countries were allowed to participate

as well. Japan evidently was an exceptionally good assignment for guys looking to fly model airplanes, run model

boats, and shoot off model rockets. When I was in the USAF stationed both at Keesler AFB in Mississippi and at

Robins AFB, the bases had very nice hobby facilities. While in radar tech school at Keesler, my friend,

Jim Flinn, and I, totally

rebuilt the engine in his VW Bug at a shop on base. It provided all the tools needed and rented out a garage bay

for the outrageous price of $1 per day (yes, a dollar a day). While at Robins AFB, I spent a fair amount of time

in the base wood shop building speaker cases, turning a couple table lamps, and making a few other projects. I was

able to fly my R/C models in a field at the south end of the base, away from the "real" airplane runways. As far

as I recall, there was no separate hobby shop on either base as evidently was on the overseas locations, but

still, it was darn nice to at least have a place to build and fly. BTW, I remember one of the roommates I had in

the barracks was able to keep his shotgun in the closet since it was for hunting. I'm guessing these days the only

firearms of any sort in base living quarters are those illegally harbored by terrorists-to-be

(waiting to commit acts of "workplace

violence").

Model Paradise: PACAF

|

Piloting C-99 control liner at Japanese-American meet becomes 2-man task.

Ukie ring at Johnson Air Base has concrete surface.

|

The fabulous hobby shops of the USAF's Pacific Air Force (PACAF) which serve Air Force personnel and their dependents,

in spite of world-famous low prices, rack up a yearly gross business of more than $1,000,000. Due to the specialized

and varied needs of the hobby craftsman a special exemption was made from the Presidential decree on buying primarily

American-made products. The PACAF emporiums stock goods from all over the world. This is not to say that they do not

"buy American," for you can find most any U. S. product your hobby work might require.

When this Far East hobby program started in the late 40's, it was considered primarily as occupational therapy.

Its directors quickly discovered that the plan had to conform to the desires of its patrons. Since it was designed

to provide a wholesome outlet for the airman in his leisure time-and some people are just not inclined towards sports

or social events - the program attracted many who were perhaps more introverted and more talented. The crafts involved

became more "expertized." The customer wanted the best that money could buy. As his tastes became more sophisticated

he became less excited about weaving a basket or building a bird house. If he was a crew member or a pilot of a B-50,

perhaps he wanted to build a model B-50 with four engines that operated, a model that was faithfully detailed. If

he was active in free flight, he wanted the latest and best kits, engines and equipment. If nuts about speed, ditto.

These guys also wanted to build 20 foot inboard cruisers, stereo hi-fi sets with professional tape decks, multiplex

and large speakers. If an R/C fan the service hobbyist sought 10-channel transmitters and receivers, plus servos and

engines which the Nats winners used! If an expert in lapidary he wanted opal or sapphire with the best of mounting.

|

All kinds of crafts and hobbies are represented at Pacific Air Force displays, here a local visitor views winning

art.

Radio control boat under test in base swimming pool.

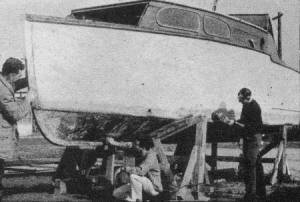

Joint project at Itazuke's hobby shop was inboard cruiser; its builders sand down fiberglass hull.

Discarded chute serves as shade at control line competition.

|

Via a common interest in hobbies excellent relationships between the native populations and the air military have

been firmly cemented. For hobby craft instructors an expert in each field is usually on hand, he may be a local "national,"

a part-time military man, or civil service personnel. This mixed participation and common interest has resulted in

the local folk and the military joining forces in putting on contests. For example, the Japanese-American air-meets

are big affairs usually held at an air base. And quite often U.S. military personnel are invited to officiate at local

meets because the Japanese modelers feel everything will then be fair and square.

Most air bases in Japan have at least one excellent control line flying circle. If not completely surfaced with

concrete they will have a 25' wide strip, with a cement center for flyer and pylon. In every case there is a safety

barrier around the circle. Usually a bleacher section is provided protected by a high wire fence. Officials have a

little area all to themselves and facilities are available during contests for a good PA system.

At Atsugi, a Navy base, there are three U/C circles of different sizes including one for combat not surfaced, plus

a control tower for the officials. Usually contracted to a local builder who uses Japanese materials and labor, some

have been built for as little as $350 which is mighty inexpensive for a surfaced, fenced field.

The Air Force hobby shops usually have separate rooms for each activity. The model builders have drill presses

and soldering irons that can be checked out at the sales stores, the woodworking shops have all the usual power

tools, saws, joiners, which the modelers use to good advantage. Each shop has individual lockers for the craftsmen

to store their personal equipment and supplies ... some even have "transient lockers" for modelers on TDY! The

walls of the shop generally have special racks for hanging models and huge workbenches for constructing the

largest of models. Policing of these areas is usually left up to the home club. We heard of no difficulties in

this respect.

When Lt. Col. Larry Rhodes was in special services for the 5th AF in Nagoya, modeling was at its peak. Col. Rhodes

mocked up and built special work benches, engine run-in stands, test rooms, and flight circles. As these were developed,

plans were drawn and printed with copies distributed to all bases. He encouraged participation of all the military

in meets. In 1956 the then Far East Air Forces contest had Byers from the Armed Forces Far East (Army), Navy and Marines

participating. This particular competition was by far the largest ever held in that part of the world. It was at Gifu

Air Base outside Nagoya and the site was perfect. The free flight area was immense, the flight circle just completed

as we arrived for the contest had a fence 20 feet high around it. Entry was thru a safety opening which protected

even the flyer on deck in case anything went wrong.

Each large air-model contest these days usually has a display of products from TMHK of Tokyo, who must certainly

be Japan's largest distributor. This concern handles only the better Japanese products. Mr. Kitimura (or Mr. Kitty

as he likes to have the modelers call him) always has the latest products and though his prices may be a little higher,

he backs up everything he sells. He apparently will drop everything to take in a meet. He always brings along prizes;

at the last one in Misawa he presented trophies and plaques for 3 places in each event

Speaking of prizes the ones given in these contests are the best I have ever seen. Almost always there are huge

trophies for the first three places in each event. Then the grand high point champ gets a bigger one and the winning

team an even larger one!

Transportation to these contests is generally by cargo plane. Local plywood being cheap, model boxes grow to monstrous

size. This makes, for some exciting times at air bases when it is necessary to change planes ... because a model hangar

8 feet long, 3 feet wide and 2 feet deep is listed merely as "one box," on the air cargo manifest. And you ain't seen

anything until you've examined the inside of a cargo airplane that has been taken completely over by modelers going

to a contest. Plans are made months ahead so all can be sure to get their models to the contest in time. They stick

models everywhere imaginable in that airplane, sometimes stuffing in two hundred. When it is time to unload, you get

the idea there is no end to them. Returning from the contest is a different story. Plans just can't be made for this

trip. Sometimes these guys are held over enroute for days, some who must make it back by a certain time go by local

commercial planes or train, paying their own fare. Frequently it takes weeks to get your models back, then there is

the problem of trophies ... lost or smashed models can mean some extra shipping room but there never seems to be enough.

One difficulty which always crops up is that some model builders can't get away to the contests. There can be a

crisis of some kind going on somewhere which requires certain fellows to stay on the job.

For this reason the 1963 PACAF contest could very well be held in April, it could also be a meet there where once

again other branches of the military will be invited. Col. R. A. Porter, head of special services for PACAF, is an

ardent model builder who has participated in many contests. An unusual modeler, too; he wins in rubber, Nordic and

speed - specially jet speed - quite a combination!

Posted August 9, 2014

|