|

In 1946, Popular Science

magazine highlighted the burgeoning potential of helicopters, detailing their

versatility and the innovative ways people envisioned using them, from hunting

expeditions and aerial orchestras to funeral services. The article underscored

the helicopter's unique capabilities, such as vertical take-off and landing, and

its proven utility during World War II in diverse environments. Commercial

helicopters were on the cusp of becoming available, with initial deliveries set

to start that year, though primarily for business and government use due to high

costs and complexities in operation. The piece also discussed the challenges

faced by manufacturers, including mechanical complexities like torque and the

need for mass production to reduce costs. By 2025, the state of the art in

helicopter technology has advanced significantly. Technological advancements

have addressed many of the 1946 concerns, such as improved fuel efficiency,

stability, and reduced vibration, while regulatory frameworks have evolved to

better integrate helicopters into urban and rural environments, showcasing a

stark contrast to the nascent stage of helicopter development described in the

1946 article.

Heli-Taxis Are Here

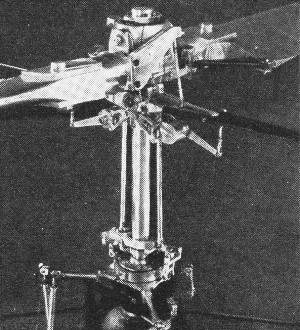

Sikorsky rotor head consists of (A) pitch-control levers, (B)

cuff or blade attachment, (C) blade, (D) "wobble plate," (E) cyclical pitch control,

(F) main rotor shaft, (G) supporting pylon, and (H) hydraulic fluid.

Manufacturers Are Forging Ahead· with Machines that Stand Still in the

Air.

By Devon Francis*

A man wrote to the Bell Aircraft Corp., Buffalo, N. Y., helicopter manufacturers,

the other day and inquired, please could he buy a helicopter to go on a hunting

expedition to Africa and wound an elephant? He didn't want to kill an elephant,

he just wanted to wound it with rifle fire. He had heard that dying elephants all

plodded off to a secret place to expire. In his helicopter he would follow the wounded

elephant and turn up a fortune in ivory.

Another man asked if he could buy a helicopter, put an orchestra in it, and have

it hover over the floor of his dance hall.

An undertaker wanted a Sikorsky helicopter to waft the mortal remains of his

customers to their final resting place.

The manufacturers did not smile charitably behind their palms. Helicopters could

do all those things. Of all the transportation vehicles engineered since the beginning

of time, the helicopter is the most versatile.

And commercial helicopters are here. Deliveries will start next month. All that

a person needs to buy one is enough money and a priority from a manufacturer.

Today's American helicopters were born just before the war and refined by use

in the Burma jungle and on China's high plateaus. They flew in weather that grounded

every other kind of aircraft. From boats standing off Pacific islands, they toted

repair parts for Super Fortresses to new landing strips. They plucked mariners from

ocean swells. The crew of one helicopter, cruising over Alaska's wastelands, shot

one of several wolves that had cornered a caribou.

In the next few months helicopters will be cruising over cities and towns and

open country on dozens of kinds of errands. They will be used for Short-range travel

by business executives, for patrolling pipe lines, and even for taxis. Crop-dusting

by helicopter will be commonplace. Hundreds of helicopters will soon be produced,

but they are not yet vehicles for private customers.

Dr. Igor Sikorsky, dean of U. S. helicopter makers, converses

with PSM's Devon Francis.

For Such Varied Jobs as These, Helicopters Are Ideal: Taxi Service,

Vacation Travel, Crop Dusting, Interurban Transport, Executive Travel, Commercial

Fish Spotting.

Sikorsky 4-place transport (left) has top speed of 103 m.p.h.

at sea level; will cruise 150 miles.

Bell 2-place helicopter (right), with cruising speed of 80 m.p.h.,

carries more than normal load of one-fourth gross weight.

Helicopters for commercial uses will precede those for private use for several

reasons. They are still too expensive to buy and maintain, they are still comparatively

inefficient (they won't go very far on a gallon of gas), they are still hard to

fly; and, finally, the manufacturers don't want their product to fall into "unsympathetic"

hands.

The manufacturers know that their product, potentially, can be sold in the millions

to the public. If it is carelessly used and serviced at this stage of the game -

if helicopters are involved in some bad accidents - the future market may be badly

affected. If, on the other hand, hundreds or thousands of helicopters are proved

out by hand-picked customers, tomorrow's market will be gratifying. Those hand-picked

customers will be business houses and government agencies.

Helicopters are expensive, first, because they are being made in small quantities.

Only mass production brings unit savings. Bell, for instance, will produce only

500 two-passenger machines as a beginning. These have been sold in advance. Helicopters

are expensive, second, because the manufacturers are writing off at least part of

their research and engineering costs on the first batches they turn out. They are

expensive, finally, because as yet they are too complicated mechanically. One of

the reasons for this complexity is troublesome torque, the tendency of the helicopter

to twist in a direction opposite to that in which the blades whirl when power is

applied.

Laymen insist on comparing helicopters to airplanes and automobiles. A two-seated

helicopter requires almost three times the power of a two-seated small airplane

and is 20 miles an hour slower. The power required to run a two-seated helicopter

would drive an eight-ton truck. But such contrasts make the helicopter people sore.

They say, first of all, that a helicopter cruises on half or less of its horsepower.

It is highly powered to permit straight up-and-down flight. They say that neither

an automobile nor an airplane will do what a helicopter will do. That is certainly

true.

They say a small helicopter will use no more fuel than an automobile if each

travels 80 miles an hour. That is also true.

They say an 80-mile-an-hour helicopter is far faster than an automobile and faster

door-to-door than a 200-mile-an-hour airplane for distances up to perhaps 300 miles.

That is true - if the helicopter can take off from the middle of town and land in

the middle of the town it is going to while an airplane pilot is getting to and

from airports.

They say that whereas an automobile must wind around tortuous curves and stop

for red lights, a helicopter travels in a straight line at a constant speed. That

is true. They say, too, that helicopters can fly in weather that immobilizes airplane

and automobile travel. And that is true.

But they do not emphasize that the things are hard to fly. A helicopter has four

controls, against three in an airplane. It demands strict attention. Yet the helicopter

people say any normal person can be taught the rudiments of helicopter flying in

eight hours of instruction. And helicopters are going to be easier to fly. A few

of them are being equipped with a brand new gadget, a governor to draw from the

engine the exact amount of power required by the pitch of the rotor blades. This

has previously been the pilot's tricky problem. Of course, there is a catch - the

governor costs no less than $800. But other simplifications will follow, just as

clash-free gears and four-wheel brakes came to the automobile.

For six weeks, winter before last, Floyd W. Carlson, chief helicopter test pilot

for the Bell company, flew a helicopter home every night and to work every morning.

He landed in his front yard and left the machine parked out in the weather. He didn't

miss a day despite sleet, rain and snow. That seemed to dispose of the theory that

under icing conditions a man who took a helicopter aloft was a candidate for slow

music and flowers.

One company figures that any airport-to-post office mail run that takes a truck

30 minutes can be negotiated by a shuttle helicopter in a maximum of five minutes.

Sikorsky's helicopters capped a series of extraordinary performances in the war

with peacetime records. One of the big ones built for the Army carried 18 persons

a short distance off the ground. It also flew a height of more than 21,000 feet

and made 114.6 miles an hour in level flight.

Bell rotor head uses "cyclic pitch" but also incorporates special

stabilizing device.

Problems in helicopter design remain. A helicopter does things that baffle even

the best of the engineers. That is understandable. Less than a quarter of one percent

of the engineering spent on perfecting the airplane has been expended on the helicopter.

It is about where the automobile was in 1905. It must develop not only greater efficiency

but also more speed, more stability - the kind that permits a motorist to take his

hands off the wheel momentarily at 50 miles an hour - and less vibration.

Efficiency is improving. The earliest helicopters barely were able to stagger

off the ground. Today's carry a "disposable load" - fuel, passengers and baggage

- of a fourth of their gross weight. The disposable load of an airplane varies from

a third to nearly a half of the gross weight.

Stability is improving. By using a stabilizing bar working on the gyroscopic

principle, plus a two-bladed "teeter-totter" rotor that obviates flap hinges at

the blade roots, Bell has proved that stability can be increased and vibration decreased.

The assorted rotor combinations being used by the 51 U. S. companies and individuals

making helicopters or experimenting with them show (in drawings at bottom of pages

84-87) that the designers are wallowing in a sea of undigested research. They know

they must simplify the rotor systems to cut cost and make servicing easier. They

know they are not getting enough lift out of their blades. They know that jet-propelled

blades would solve many of their problems at one fell swoop. Jet propulsion, whirling

a rotor just as water whirls a lawn sprinkler, automatically would dispose of torque.

Torque does not develop unless power is applied directly to the rotor. But jet reaction

applied to helicopters is exceptionally wasteful of power.

Border Patrol, Air Sea Rescue, Package Delivery, Emergency Transport,

Airport-Post Office Shuttle.

Side-by-Side, Torque Correction by Jet, Longitudinal, Longitudinal

Intermeshing.

Kellett XR-8 (left), Army machine has intermeshing rotors. Its

245-hp. Franklin engine is behind pilot.

One-Place "Roteron's" (right) 25-hp. motor is mounted between

coaxial rotors.

What the helicopter people would like most to know right now is what rules are

going to govern helicopter flight. If helicopters are forbidden to land in midtown,

their usefulness will be cut in half. That's where helicopters shine - doing things

that airplanes can't.

Pilot Carlson of the Bell company gave me a ride in the first and, as yet, only

helicopter commercially licensed by the federal government. It is a two-place job

with a 175-horsepower engine that cruises at 80 miles an hour. Once off the ground,

I could understand why helicopter people get wacky over their machines.

We sat in a comfortable cockpit like that of a small airplane except that a plastic

bubble took the place of fabric and metal. It contained one additional control,

that for rotor blade pitch. Carlson nudged the throttle open. We went faster, straight

up, than the world's fastest express elevator. One moment the ground was a couple

of feet below. Seconds later it was hundreds of feet below.

Forward flight was like that in an airplane. Certainly there was no more vibration

than there is in an airplane. Possibly there was less. But I did notice an odd,

modified gallop. It felt like an automobile on a washboard road.

"That's not normal," explained Carlson. "The blades need adjusting. You get that

when one blade doesn't 'track' in the path of the other one."

The helicopter gained and lost altitude and speed at his will. Though an extremely

strong wind was blowing, we felt no air bumps. The whirling canopy of blades above

us smoothed them out. We came around for a landing quite high and very fast, and

of a sudden we were just hanging there in space. Carlson had gone from 60 to 0 miles

an hour in a twinkling. A helicopter can stop twice as short as an automobile.

"This is an autorotative landing," he said. He throttled back. The rotor, freed

of the engine through an over-running clutch, spun on its own as our descent produced

a rush of air against the blades. We had gone up like an elevator, and now we came

down like one. The helicopter glided like a streamlined brick. Then, just off the

ground, Carlson hauled back on the stick. The blades cushioned the fall and the

wheels touched as light as eiderdown at a forward speed that could have been no

faster than a walk.

For fun, Carlson took off again, backed up a few feet and landed with engine

power. p>

One of the company employees, who has been watching the helicopters fly for years,

was waiting for me as I climbed out. "That was wonderful," I said, "and now let's

go get a beer."

"Do you mind waiting a minute?" he replied. "I want to see the ship make one

more hop."

That's the way helicopter people are.

* Associate Editor, PSM, and author of "The Story of the Helicopter." published

this month by Coward-McCann, $3.

|