|

The type of glass referred

to in this 1953 Science and Mechanics magazine article is not the solid

sheet type made from sand (silicon), but fiberglass. It has strands of glass

mixed into the plastic weave, hence the name. It is the glass component that

causes itching as it pricks your skin. Breathing it into your lungs is dangerous

as the minute particles of glass can lodge in the tissue. Typical of the era,

the workers shown handling the fiberglass have no protection for eyes, nose,

mouth, or skin. Fiberglass ended up not being the material hoped for because it

ultimately could not stand up to the extreme structural and thermal loads

typical of high speed aircraft. It was also not tolerant of being exposed to

intense sunlight while sitting on a tarmac. The few commercial and homebuilt

fiberglass airplanes need to be painted white to reflect as much ultraviolet

light as possible to prevent delamination and deterioration of the components.

Carbon fiber on the other hand, which came about decades later, has proven to be

useful.

Glass-Plastic Aircraft Challenge the "Heat Wall"

Artist's conception points up the tigerish grace of the ultrasonic

glass aircraft of the future.

By James Joseph

"The plane of tomorrow will be glass, probably glass fabrics impregnated with

resins. We're not even thinking or designing in terms of metal anymore."

This remarkable prediction by Thomas E. Piper, Northrop Aircraft's director of

materials, is echoed by other materials experts in the field of aircraft design.

And the facts - including data on superior heat resistance and lower costs - are

there to back up the statement, which refers to military planes and, indirectly,

to civilian aircraft.

This "substitute for today's aluminum airplane skins," as Piper puts it, consists

of half a dozen layers of glass fabric, impregnated with phenolic resins and cured

in a heated mold. Such a fiber-glass-plastic laminate is the sleek clothing that

the well-dressed jet or rocket plane of 1958 may wear. It's a good bet that smaller

private planes also may be decked out in glass and plastics bi that time, and they

may sport a lower price tag, too.

The immediate reason for pushing the development of fiberglass-plastic laminates

is the fact that aluminum aircraft skins will not stand up under the high temperatures

generated by air friction at the super-sonic and ultra-sonic speeds our planes are

beginning to attain.

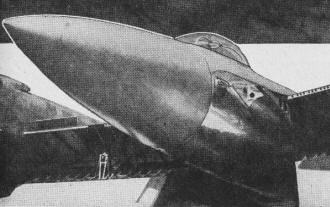

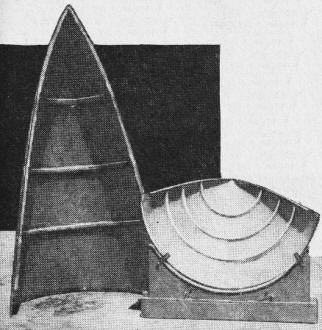

End result of glass-plastic molding is this sleek, clean tailcone

of laminated glass fabric. No riveting - a costly, time-consuming job - was required.

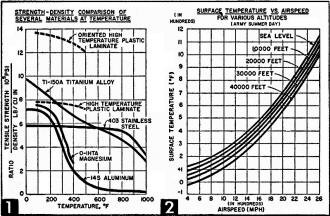

This chart (Fig. 1), released here publicly for the first time,

shows why metals can't be used for skins on jet planes that will ram the friction

barrier at twice the speed of sound. Aluminum and magnesium lose their tensile strength

as temperature rises. Titanium alloy is too expensive and stainless steel is too

heavy. Glass-plastic laminates probably hold the answer.

Fig. 2 illustrates how surface temperatures of plane's skin increase

with the air speed at various altitudes.

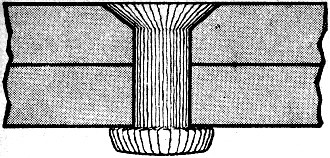

Glass rivets - as designed for the future - will be necessary

to maintain uniform expansion of fastener and material during high-speed flight.

Glass laminate tailcone, fabricated in two pieces in mold, emerges

after the baking process looking like this.

A workman in Northrop's plastic shop impregnates cloth in mold

before laying on the pre-cut glass fiber.

Can glass take these temperatures? Certainly not ordinary glass, which is brittle,

cracks under sudden heat shock, and is unable to endure wide temperature variations.

But bond several sheets of fiberglass with a phenolic resin and you come up with

something else again. The most valuable characteristics of this material, in comparison

with aluminum, for instance, is its ability to retain a much higher percentage of

its tensile strength after prolonged exposure to temperatures in the 500° F.

range (Fig. 1).

That, briefly, is the "why" behind the development of glass-plastic skins for

military aircraft. A parallel result probably will be the production in a few years

of better, cheaper small planes for private use. As a matter of fact, that picture

already is beginning to come into focus.

Hundreds of aircraft parts are being molded from glass fabric right now, including

various airs coops, tubing, and entire sections of some classified military planes.

Some British manufacturers estimate that use of the laminates for small plane skins

would reduce their overall cost by 30%. Northrop engineers expect "at least 25%

reduction."

All other things being equal, that could mean that in 10 years the glass-skinned

counterpart of a metal plane that now sells for about $19,000 will be available

for a little over $13,000. The plane that retails today for $13,000 may be priced

as low as $9,000 when it's produced in glass-plastic, assuming of course, that other

costs remained constant. This envisions, also, a more simply constructed fuselage

that perhaps would be molded as a single unit. Of course, these glassy jobs can't

- and probably won't - compete price-wise with the fabric-and-dope-skinned models,

that sell now for prices ranging from about $3,700 to $7,000.

Designers visualize the supersonic plane of 5 to 10 years hence as having fiberglass-plastic

wings, ailerons, stabilizers, fuselage, and even fiberglass rivets fastening its

laminated glass skin to its titanium and stainless steel low-density frame. Fuel

will have lower vapor pressure than any today so as not to boil at speeds in excess

of 2,000 mph. Dry, heat-resistant metal powder will lubricate the plane's powerful

jet engines.

This is no dream. The British hope to flight-test a glass-covered plane this

year, and numerous U. S. experimental planes already have been built with portions

of their fuselages and .wings fabricated from plastic-glass fabric.

All this is a clear admission that having overcome the sonic barrier (smashed

in 1947 when U. S. Air Force Capt. Charles E. Yeager shuttled his rocket-engined

Bell X-1 some 1,100 mph), airplanes have run smack into another - the thermal barrier

(also dubbed the "Ram Compression Temperature Rise" and "heat wall"). Overcoming

the thermal barrier means revolutionizing the basic ingredients of modern aircraft,

to withstand the terrific temperatures generated by friction when a plane hurtles

through space at double, triple and quadruple the speed of sound. As the speed of

a plane is doubled, its friction-temperature quadruples. Thus, at 1,000 mph (and

at 40,000 ft.), a plane's skin is a feverish 120°F. At 2,000 mph, skin temperature

is a red-hot 575° at 40,000 ft. and a sizzling 700°F. at sea level (Fig.

2).

Magnesium and aluminum alloys lose their stiffness and become pliable at 500°F.

Both melt between 1,200-1,400°F. Titanium is too expensive ($20 a pound) and

scarce. Stainless steel is too heavy for aircraft covering. It appears that metals

are fine as long as you're poking through the atmosphere at not over 1,500 mph,

but none of today's metal-skinned, piloted aircraft designed for sustained flight

could stay in one piece much over 1,800 mph. The ship's aluminum skin would soften

from the terrific heat. In a matter of minutes the plane would rip apart in mid-air.

You've read about unsolved instances where faster-than sound aircraft exploded

during power dives - and some of the "flying saucer" interpretations of why these

planes disintegrated. A more realistic picture would be, that during a high-speed

dive the ship crossed the threshold of "safe" supersonic speeds. Its aluminum skin

softened under the terrific friction temperature and burst like a ripe melon.

Our fastest fighters are approaching thermal barrier speeds now (1,600 mph and

a friction temperature of 500°F. at sea level). Our old standby, aluminum alloy,

has a nervous break-down at supersonic speeds in the Mach II range (1,500 mph and

above). At room temperatures its tensile strength is 62,000 lbs. per square inch.

Preliminary tests show that after only a few minutes at 500°F., its strength

falls to 18,000 psi - a loss of 70%. Today's aluminum skins, subjected to the 500°

test for a full 24 hours, lose nearly 90% of their strength. Magnesium alloys aren't

much better.

On the other hand, glass-fabric laminates with a tensile strength of 80,000 psi

at room temperature, have been found to lose few or none of their mechanical properties

at 300°F., and only 20% strength after exposure for 24 hours at 500°F.

The materials weight-strength chart (Fig. 1) reveals why metals are doomed as

aircraft covering, and why glass fabric will come into its own. Aluminum would have

to be 7% times as heavy (and many times thicker) than a given thickness of ,glass-plastic

to withstand sustained temperatures of 500°F. Oriented glass-plastic fabric

(with its glass fibers rigidly controlled and aligned) can be 11.5 to 12 times lighter

than aluminum - yet retain much of its strength at 500°F. The weight of a material

compared to its strength is a big and decisive factor in choosing any new material

for airplanes.

Glass fabric's insulating and non-corrosive features are other big advantages.

Today's all-metal aircraft are heat conductors. Even a few degrees temperature rise

on the airplane's skin is transmitted throughout the craft - and turns an unairconditioned

cockpit into a hot box. Glass and plastic are poor heat conductors.

"Fact is," says Piper, "after glass, we'll probably experiment with asbestos-covered

planes. The British already have worked with asbestos." But asbestos won't be needed,

some designers believe, until planes fly so fast that their skin temperatures soar

to 1,000°F. (2,600 mph at sea level).

Simplified Production

Glass fabric-phenolic laminates should revolutionize production methods, too.

Today's aircraft contain thousands of rivets which hold their aluminum skins together.

Skins are pressed from sheet aluminum very much as are automobile bodies. After

or before forming, the metal is machined and rivet holes are drilled. All this means

hours and hours of machining - most of it precision stuff requiring skilled hands

of which there's always a scarcity.

Using glass-fabric, most of the machining and drilling would be eliminated. First

comes a mold - a huge plastic cast. Into this are fitted layers of pliable fabric,

each layer "glued together" with the adhesive-like phenolic resin. When the layers

are built up to desired thickness, the mold is compressed and heated under 15 to

800 pounds of pressure per square inch to give the necessary tensile strength.

One of the difficulties to be overcome is the fact that glass fabric, despite

its other sterling qualities, doesn't stand up too well under wind erosion - the

factor that creates the friction-temperature in the first place. The aircraft designer,

like the farmer, is deeply concerned with the problem of erosion.

"Maybe," says Piper, "we'll have to mold very thin stainless steel foil to the

exterior glass skin, especially on leading wing edges." Erosion becomes a serious

problem at Mach II (1,500 mph) and above.

Aircraft engineers already have launched research on fiberglass rivets and say

that although tests to date haven't been too successful, there's no reason why they

shouldn't work. Metal rivets aren't satisfactory for joining glass to glass, or

glass to a metal frame. The reason: At high temperatures metal rivets expand, and

at lower temperatures they contract. This loosens the rivets and diminishes structural

rigidity.

Fuels and lubricants also must change radically to meet new conditions of higher

speeds and heats. At two or three times the speed of sound, hydrocarbon engine fuel

(high test aviation gasoline) boils. Various methods of refrigerating fuel tanks

have been suggested, but all involve added weight. The need is to develop a readily

available fuel having such a low vapor pressure that it will not boil at high temperatures.

High-temperature lubricants probably will be of the metallic dry-powder or dry-film

types-such as molybdenum disulfide.

In the next few years big things will be coming out of our aircraft plants. And

I don't mean just the B-47. Dead ahead looms the thermal barrier, and with it the

era when glass-plastic-and perhaps asbestos - will replace conventional metals.

Posted June 8, 2024

|