|

I have never been involved in FAI C/L racing,

but I imagine things have changed fairly significantly since this article appeared

in the January/February edition of American Modeler magazine. It is the second in a two-part

installment, and unfortunately I do not have the December 1962 edition yet.

Secrets of International Team Racing - Part 2

Second of two articles by AMA Control Line Champion Paul J. Burke

You have your FAI Team Racer built, so flying it comes next. The level of skill

required to make a good competitor means that you or your pilot must start out with

some experience, primarily racing type. International event pilots must know the

importance of "down elevator". Main cause of torque rolls and slack lines is a full-up

take-off. This type of maneuver is stupid, and especially wrong in FAI. Why down

elevator and how much?

Any racing plane has rapid acceleration. This acceleration generates a lot of

lift. If the plane makes a normal uncontrolled leap-off, there is nothing except

tip weight to prevent a roll. You know what limited effect tip weight has. Down

elevator prevents this sudden build-up of lift from marring your take off. Just

a little down will enable the plane to fly off the ground in a stable climb. The

usual American-style Rat Racing VTO is out anyway.

The minimum height of 6 feet and the maximum of 9 feet, with up to 19 feet in

which to pass, mean that in addition to a stable plane, a careful man is necessary.

This straight and level 3' grooved flight must be practiced continually, in all

types of weather, preferably with someone else flying in the same circle. Good FAI

pilots can fly within inches of each other with no sweat.

The rules require the pilot to fly with the control handle against the centerline

of his chest. This is an awkward position, but it means the pilot is assisting his

plane as little as possible. It also makes the pilot to keep up with his plane.

Seldom do you overtake in usual Rat Racing fashion by first passing the flyer, then

his plane, because he is lagging behind.

Passing requires care. The preferred way is to pass as close as possible to the

job you are overtaking to eliminate seconds (distance) lost in a long climb. This

is the only time you can take your hand from your chest. Passing is such a delicate.

maneuver you must practice it with someone else.

A Team Racer is not essential to provide the fundamentals of low altitude, high

speed flight. Rat Racers are capable of the same quality flying if designed and

built properly. It is certainly less expensive to replace a Rat Racer should you

goof.

Fuel (as mentioned in our previous article) is a controlling factor in performance.

There are no exotic fuels, but there are good and bad fuels. I feel that commercially,

Cub Diesel is the one to use. Addition of about 5% ether will help it.

The fuel ingredients if you mix your own are almost standard. The Oliver Tiger

formula is used universally. This is 20% oil, 30% Ether, 50% Kerosene, 3% Amyl Nitrate

(yes, it adds up to 103%). The oil obviously is for lubrication. Bakers AA Castor

Oil is the best you can use. Synthetic oils such as UCON LB1145 should be merely

as additives - no more than 10%. Used straight, they cause hot running.

Kerosene is the power ingredient. There is every advantage to buying the best

grade available. I use the chemical quality, since it gives me more consistent performance

than the. gas station type. Depending upon your average climatic conditions, you

might not be able to use a full 50%, but will have to increase the ether content

to cool off the fuel.

The ether, anesthetic grade, or ethyl ether, is to ignite the kerosene. Although

the engine will run on less than 30%, the higher compression then required over-strains

the piston, rod, and crankshaft. Ether is also used to cool the fuel, by lowering

the ignition point. More than 40% however, will rob too much power. Determine the

proper balance of ether and kerosene by trial and error.

Amyl nitrate, and its replacement, propyl nitrate, smooth out the high rpm ignition.

Don't skimp here. Too little will cause immediate overheating problems.

Should you mix your own, there are three handy tools. A 500-ml graduated cylinder

to mix large quantities and percentages, a 50-ml graduated cylinder for small quantities

and small percentages, and a large funnel to help pouring.

Propellers determine speed and can help or hinder lappage. Obtaining the proper

size is a matter of test with the aid of a stopwatch and lap counter. Trim prop

diameter and area distribution until performance is where it cannot be improved

with a recorded prop-fuel combination. If this is not high enough, try different

combinations until you attain competitive times. No one else is going to do it for

you.

Your pilot must learn a new technique to derive full benefit from the mono-wheel

gear. 99% of the European Racers use this. It is most important to have the wheel

as far to the inside of the circle as possible, to provide maximum pull-out during

takeoff and landing. This automatic pull-out explains its popularity. A wheel which

cannot come off the strut and a tire which stays on the hub are vital. The length

of the strut is not as important as the torsion type mounting. This mounting will

allow a plane to land roughly without serious damage or bouncing. The take-off and

landing procedures should be practiced at every opportunity, it is here that the

most errors are made by pilot.

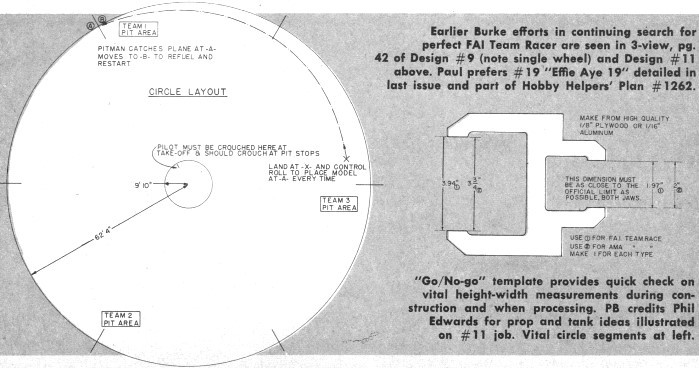

Suppose we run through a race? First, the circle layout deserves attention, since

the conduct of the race is determined by its various features. This idea is to provide

at least 60 feet of clear area in which to take-off and land. This is to eliminate

as much as possible conflicts or accidents during this critical phase. It is accomplished

by dividing the outer circumference into six equal segments. Re-fuelling and restarting

can only be done in one of these segments. So pilot and pitman must coordinate their

efforts to get their plane serviced at the same segment each time it lands.

The distance between the mechanics' outer circle and the pilots' inner circle

is equal to the length of the control lines. The pilot cannot leave his circle,

the mechanic cannot enter the outer circle.

The space between is a no-man's land - there no one is permitted. This is to

prevent planes from hitting people. If your plane stops inside no-man's land beyond

reach ... that's all, Brother.

Since line length equals the distance between the two circles .the pilot can

clobber a pitman if he brings his plane across the outer line too soon. It is also

possible to taxi into lines held off the ground. This hazard is the pitman's responsibility.

The FAI is very strict on any interference with a competitor so caution is needed

as well as skill and determination.

Control lines are 626 inches from the handle center to the plane center. The

.012 inch diameter may seem oversize, but the FAI desire for safety is again in

evidence. Heavier lines do not curtail performance much. Stranded lines are safer,

since in humid or wet weather they slide, solid lines may not.

The race is run over 100 laps, against a clock. The altitude limits mean the

distance flown is that intended by the rules. Each team is permitted at least one

official attempt, with a maximum of two. The three entries with lowest heat times

fly together in a 100 lap final.

The start differs from any in AMA country. Each team picks its own take-off position

prior to entering the circle. Then comes a thirty second warm-up period where the

engines run to finalize adjustment. At the end of thirty seconds all motors are

stopped, the tanks topped off, and each mechanic stands away from his plane. Pilots

kneel with their hands and, handles on the ground. The period immediately after

warm-up time is also thirty seconds in duration. The last five seconds are usually

counted down. At zero, the mechanics start motors and launch the models. The clocks

start and lap counters are readied at the zero count.

Once airborne a pilot must not interfere with another pilot or model. If he is

passed, he must not hinder the faster plane; and when doing the passing, he warns

the pilot he is overtaking. Keeping the model within that three foot high flight

path shared with one or two other planes is not as easy as it looks.

When his engine quits, the pilot moves out to the edge of the center flying circle

so his pitman can snag the plane. Missing your pitman is the easiest way to lose.

Once the pitman has the plane in hand he places it outside the circle segment mark,

refuels, flips the prop and releases the model - assuming he has practiced this

many times and never varies his routine.

The pilot gets up from his crouched position and rejoins the other two flyers

at the center of the circle. As soon as a plane flys 100 laps, the clocks on it

are stopped.

You are new to racing, so what times should you shoot for in the beginning? Six

minutes is fairly good .for any non-National or International event. Should the

contest be of National importance, 4:45.

How can you ever do 6 minutes, you may ask, after your first 60-mph 15-lap flights.

Take the engine out of the plane, if it's an Oliver, run it for an honest hour,

on an 8x4 prop. This should free it up for more mph's and non-stop laps. Then put

it back in the plane and PRACTICE. Windy weather, calm weather, rain and shine,

you must know how both plane and engine will react.

So read and heed, build our plane, learn your engine, study the rules, practice,

and maybe you will end up among the leaders in FAI Team Racing. After all, who couldn't

use a free trip to Europe?

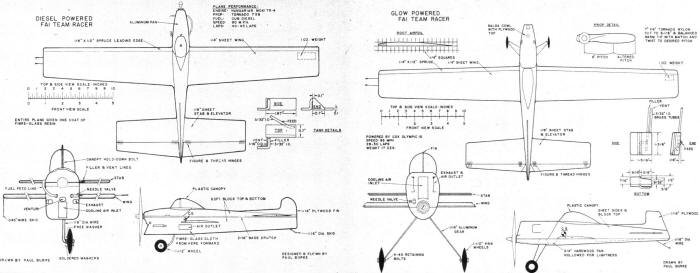

Earlier Burke efforts in continuing search for perfect FAI Team Racer are seen

in 3-view, pg. 42 of Design #9 (note single wheel) and Design #11 above. Paul prefers

#19 "Effie Aye 9" detailed in last issue and part of Hobby Helpers' Plan #1262.

"Go/No-go" template provides quick check on vital height-width measurements during

construction and when processing. PB credits Phil Edwards for prop and tank ideas

illustrated on #11 job. Vital circle segments at left.

Posted July 14, 2012

|