|

I love photos of the venerable old DC-3s in action,

whether they be performing the role of a passenger airliner, a cargo hauler, or military

utility vehicle in the designation of C-47. My only exposure to a real one was after

paying $2 at an airshow to walk around inside one. Some day, before the last DC-3 is

retired or converted to (ugh) turbine power, I hope to purchase a ride on one. Back in

the 1940s, when this story was written for Air Trails, DC-3s were revolutionizing

the air industry on all fronts mentioned. If you were a regularly flying air traveller,

chances are you flew on a DC-3 at least once. It is hard to imagine the following line,

implying that there was still some doubt in some peoples' minds about what direction

the aviation industry would move: "President of Air Cargo Transport Corporation, oldest

and largest all-freight line in the business, Penzell is firmly convinced of the future

of air transport - so much so he has sunk his whole fortune and energies in it."

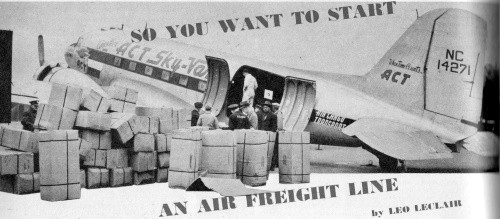

So You Want to Start an Air Freight Line

By Leo LeClair

Glowing Newspaper Publicity has Badly Warped the Air Cargo Line Picture

So you just got out of the Army; you were a pilot

ill the Eighth Air Force, you saw action in both the European and Pacific theaters, you

hold a pilot's and a mechanic's license, you have a few thousand bucks saved up in flight

pay, and you and your buddy think you'd like to start an airline. An all-cargo line,

you reckon, because that's the newest wrinkle. You've been reading in the papers how

they fly everything from furs to furniture these days, and you figure you'd like a piece

of that pie in the sky. So you just got out of the Army; you were a pilot

ill the Eighth Air Force, you saw action in both the European and Pacific theaters, you

hold a pilot's and a mechanic's license, you have a few thousand bucks saved up in flight

pay, and you and your buddy think you'd like to start an airline. An all-cargo line,

you reckon, because that's the newest wrinkle. You've been reading in the papers how

they fly everything from furs to furniture these days, and you figure you'd like a piece

of that pie in the sky.

Take it from the men who know, bub - it shouldn't happen. It shouldn't happen to anyone

who isn't willing to throw three or four hundred thousand dollars in the kitty and get

exactly nothing in return. It shouldn't happen to anyone who isn't willing to wait for

at least two years - years that will seem like centuries-for the business to start rolling.

It shouldn't happen to anyone who hasn't the patience of sixty airborne Griseldas.

You're wondering why. You've been reading the glamorous newspaper stories and you

want an explanation. You argue that the air transportation industry jumped ahead at least

a couple of centuries during the last crowded war years. That's only a slight exaggeration,

it's true. The Army's Air Transport Command, the Navy's Air Transport Service, all undertook

and successfully completed tasks which would have been laughed off before the war as

something you'd see in the movies. The accounts of their, accomplishments, carried in

the nation's most trustworthy newspapers, were all quite valid.

But to the hardheaded businessmen you meet when you start your all-cargo magic-carpet,

it doesn't mean a thing, son. And the brutal reason is - cash, Cold, hard dollars, the

same shekels that meant profit or loss to any business before the war, spelling the same

words now that the war is over.

These dollars figured only negatively in the terrific record's set and shattered by

the war's air transport - a fact too often glossed over today in attempts to make exciting

news copy. The business of commercial air transport is to make money, having provided

reliable and profitable service. The business of the Army and Navy, indeed the business

of all of us during the war, was to win it. At any cost. There was no profit to be made

save that of. victory, which was profit enough.

In short, when General of the Army Henry Arnold got reports of a Monday morning on

the progress of war transport over the weekend, he did not ask, "How much profit did

we clear?" Or if asked it, he meant how much did we save in lives, in time, in enemy

losses.

Peacetime commercial operations are a different matter. Victory is won. The people

who undertake to run an airline these days, whether for cargo or passengers, look at

the ledgers. They scream with pain, furthermore, when the story is written in red ink.

The youngsters who have started air transportation ventures since the end of the war

have been misinformed on this point as they have been on many others. And it amounts

to nothing less than downright robbery to let them think all they need is a converted

C-47 and they're on their way to an all-cargo heaven.

To run a profitable, customer-filled air freight business, you need a lot more than

an airplane. You need many airplanes - a whole fleet of them. You need traffic men, maintenance

men, freight handlers, salesmen, advertising men, bookkeepers, research men, and men

from almost every other profession you ever heard of. You need weather information, market,

figures, cost figures, publicity, shipping data, insurance. hangar facilities, landing

rights, and trucking. And, as if that weren't enough, you need office space, radio facilities,

and relief crews.

But the acquisition of equipment and personnel is only the beginning. You can have

the finest crew and equipment in the world; and you still haven't an airline. You haven't

even begun yet, as a matter of fact, without the next item (and this is the one that

kills): customers.

It is no lie that the public has been sold on air transport. They have been sold for

a long time. They have also been sold on mink coats and Cadillacs. But you can't conclude,

therefore, that minks or limousines sell like hot cakes. 'Tain't so.

Perhaps in the millennium, but certainly not in the present age, can air cargo promise

to fly freight for a nickel. It can't be done, any more than diamonds can be bought at

Woolworth's.

That doesn't prevent aerial freight cars from being a valuable medium for perishables,

valuables, and quantity commodities, that's' true. Lobster, for instance, highly perishable,

is a proven ideal air passenger. So are newspapers. and so are the fashions which smart

shops now order by air in quantity. The cargo list is exhaustive, but behind each item

is its peculiar suitability for air transport.

While an increasing number of staples is joining the lists on air cargo waybills,

Eager Joes all set to attach their silver wings to box cars should realize there is a

large amount of freight which will continue to be carried by rail for a good long time.

Coal, for instance, and other ores, oil and grains, or livestock or building materials.

No matter how efficient your airplanes, you are probably pretty safe in assuming they

won't ever come in very close contact with grain elevators or coal pits.

There are exceptions to prove the rule, of course, cases where a staple as ordinary

as waste baskets has to be flown to meet a rush order on a rail embargo. But you can

put your money on highway and rail transport for waste baskets as a rule.

Customers ,to start with is point number one. Point number two is customers for return

loads. It is safe to say that when Jason went after the Golden Fleece in his good ship

Argo, the angle that intrigued him about the whole deal was the utter lack of whimsy

in it. There was a return load to be had! Legend doesn't record that Jason had a cargo

to take with him on the journey to the Fleece's home office, but it's even money he had

something or other besides ballast.

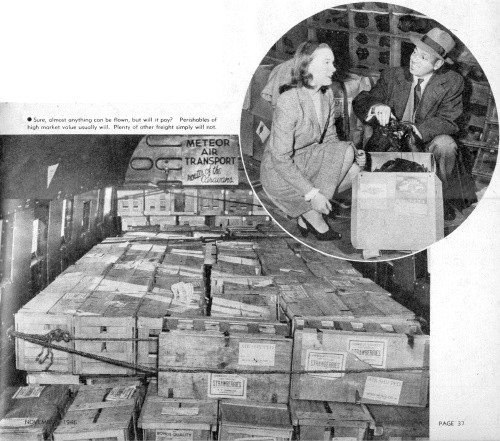

Sure, almost anything

can be flown, but will it pay? Perishables of high market value usually will. Plenty

of other freight simply will not. (photo left) Sure, almost anything

can be flown, but will it pay? Perishables of high market value usually will. Plenty

of other freight simply will not. (photo left)

Modern Jasons haven't changed. For the deal to go off, there has to

he paying freight both ways. In other words, it won't do you a bit of good to have a

year-long contract to fly flowers from Florida to Cincinnati if you have to ferry back

with an empty plane day after day. Flying an empty C-47 is, for all practical purposes,

just as expensive as flying a full one. You'll never even break even.

But to get down to specific cases. Take a look at the cargo lines now in operation;

ask their directors how the sledding is. To a man, if their publicity staffs aren't putting

words in their mouths, they'll tell you it's rough.

Ask H. Roy Penzell, for example, who is probably air cargo's most faithful disciple.

President of Air Cargo Transport Corporation, oldest and largest all-freight line in

the business, Penzell is firmly convinced of the future of air transport - so much so

he has sunk his whole fortune and energies in it.

But he will be the first to tell you that getting his flying freight cars into the

profitable operations stage was the biggest job he ever tackled. Questioned, he re-enacts'

the brow-mopping he did for the long months that passed before his ACT Sky-Vans began

to show a profit.

"I never saw such comprehensive research in my life as we did just to find out how

to operate," Penzell explains. "We had tables of market figures that reached all the

way up to the seventy-sixth floor of our Empire State Building Offices. We had one of

the best pilots in the business. Dick Merrill, conducting tests for the most suitable

aircraft till he was eating the paper he wrote his results on. ACT flew thousands of

expensive miles on dead-head trips just to try out all comers as possible cargo. Fortunately,

we had, and have, a lot of dough behind us. Otherwise we could never have carried on

the extensive tests we did.

"Maybe it's unbecoming for me to attempt to ward off possible competitors, but I have

no compunctions about it. I can square myself by putting it this way: It's a free country,

boys, and the field of air cargo is a tremendous one. If you want to jump in, go ahead.

But may I suggest you bring a pair of water wings to the tune of several hundred thousand

dollars ?"

Penzell is a youngster himself, only thirty-five. The fact that he is talking to other

young men makes his understanding of their problems greater. The fact that he has made

himself a tidy fortune in advertising and garment manufacturing bespeaks his acumen as

a businessman, His advice is worth the listening.

He intends, and already has started, to make a killing with air cargo. But not Without

a lot of headaches, past and future. Take those lobsters mentioned earlier, for example.

Penzell's ACT had to undergo several months of expensive experiment, fatal to any outfit

unable to absorb the costs, before they found the right container for shipping live lobster

by air. With the price an extravagantly pretty penny, the test could just as well have

laid a great big lobster egg. That's the chance you have to take in the air cargo business,

Penzell says.

The problem was that the lobster as it used to be shipped by rail went in big fifteen-pound

barrels packed with ice. It made the trek from Maine to New York in a day, arrived in

city markets with thirty to fifty percent spoilage and a loss of flavor that brought

tears to the eyes of any Down Easter.

Obviously. it would be advantageous to ship the lobsters by air. But no lobsterman

in his right mind was going to pay the air freight on heavy ice-packed barrels. In any

airplane, space and weight are commodities far too precious to be squandered like that.

For ACT, eager to get the lucrative lobster business, the only thing to do was to design

an entirely new, lightweight container.

While the container must be light, it had to be durable and sturdy. It had to be waterproof,

too, yet avoid being so tightly sealed that the lobsters suffocated or even got overheated.

And, above all. it had to be cheap, otherwise shippers would have none of it.

A t the top of the container there would have to be a removable tray , to be filled

with ice in case the plane was grounded some place where the temperature was too hot.

At the bottom there had to be another tray, under a false bottom. This would be to catch

the liquid which lobsters exude when packed in the container. If they reabsorb this liquid

it is fatal to them. Hence, they cannot lie in it.

ACT researchers, lobster men, and container manufacturers went into a huddle. Hair

was torn in big gory clumps for a couple of months, and the walls were battered with

the force of the heads which had been knocked against them. Six, different sample containers

were tried out. One of them leaked, another one was too heavy. A third one was ideal

but it cost too much. Numbers four and five were too complicated for packers to handle.

Number six finally hit the jackpot. It weighed only four pounds, held fifty pounds

of lobster, was cheap to manufacture, could be used more than once. It worked like a

mermaid's charm, and is being used today to bring in the lobsters. And they love it.

They arrive in metropolitan markets still fresh and cantankerous, full of seaside flavor.

Not one dead lobster among them, either, in all ACT's handling. of them.

The experiment was a success, in short. But it cost plenty. Could you have taken that

chance with the airline you're contemplating? Could you have stood the shellacking if

it had failed, as Penzell warns, it might have? If you could have taken that one without

flinching, then turn to the garment shipping business.

Convinced it had a gold mine to offer to garment manufacturers in its fast delivery

of fashion, a very perishable item, ACT went after the apparel trade right from the start.

Digressing a moment, it's interesting to note how ACT came to define fashions as a

perishable. Starting from the premise that air freight was particularly well suited to

the needs of perishables ACT soon found that the word did not apply to foods and flowers

alone. Perishables in the air transport sense of the word also meant publications, since

today's newspaper is valueless tomorrow. It also meant fashions.

So it was that ACT salesmen went out loaded with statistics to show the vast amounts

of garments shipped by rail from garment centers daily all over the country. They also

had figures to show the time lost in transit, the large and undisposable stocks which

clothing dealers had to have on hand, the losses from these high static inventories;

then," by contrast, the quick turnover, the easy reordering afforded in air freight.

The salesmen wound up at first with exactly nothing. Shippers, agreeing to the veracity

of the figures, nevertheless shook their heads when asked for contracts. They were leery

of the way their dresses and suits would be packed on the planes. They wanted proof their

merchandise wouldn't get dirty, that it wouldn't absorb gas fumes, that a million other

airborne mishaps wouldn't befall their babies.

To prove their point, ACT salesmen had to take the clothiers right out to the hangar.

Bug-eyed, the shippers watched as rack after rack of clothing was transferred to other

racks athwart the planes' interiors", No boxes,. no packing. just hang the stuff in the

planes as you would in a closet.

They saw that the big flying freight-car C-47's were dust-proof, yet ventilated to

avoid any accumulation of odors. They saw that the interiors were spotlessly clean, free

from all grease and dirt. They saw those racks. too, and that clinched it. For they realized

that boxes, an expensive item. would not be necessary when they shipped by air. Furthermore.

there. would be no pressing necessary at the point of destination - another saving. The

dresses could be. taken right off the plane racks and hung in the store, still unwrinkled.

Not only that but ACT had perfected a drop system whereby the dresses hung at different

heights on the racks. In this way full space was utilized, top and bottom.

But suppose some snag had developed. Would you have had the money to absorb the shock

after spending all that amount on salesmen and demonstrations and plane fittings? Because

not all the experiments are a success, Penzell always reminds you. In the beginning,

for instance, ACT thought it had an ideal passenger in the oyster - until it was discovered

that oysters hemorrhage when they fly more than a couple of thousand feet up, and that

the cost of pressurizing to avoid this would make the oysters too expensive for the average

consumer.

After you've conducted the expensive research necessary to find out what you can and

cannot fly, one of the next problems you hit is that of alternative transport. Despite

the miracles of modern flying there are still times when the weather keeps your planes

grounded. In such cases, the shipper wants assurance of a very concrete sort that substitute

facilities are available. Before ACT could begin flying the New York Times and the New

York Herald-Tribune to Washington, D. C, every night, for example, the publishers of

those twp world-famous papers had to know that a system had been set up for shipping

the papers by rail in the event of bad weather.

As the arrangement worked out, the late editions of the Times and Trib leave Newark

Airport every morning at three, reaching the capital in time to hit the breakfast table,

an attractive feature for the advertisers in those papers. When it rains, the earlier

edition of the paper is sent on by rail. In order to have an agreement such as this avoid

disastrous snafu, though, you have to have good weather information and equipment, and

the financial reserves to take the loss when the rain wets you down. In short, you couldn't

depend on a paper alone to keep your line going, no matter how steady the contract.

The crux of the warning which Penzell draws from his own history is that while it

has been successful, some of its trial balloons were fiascos bad enough to set a smaller,

less well-heeled airline right back on its tail skid.

His view is that there is a lot of money to be had in air cargo, but because it is

big, it demands big investments. Other air freighters agree with him. Slick Airways,

for example, has the Slick oil millions behind it. National Skyways has heavy Wall Street

backing. According to Fortune magazine, these three are the leading triumvirate of non-scheduled

air cargo-ers.

As for the scheduled operators, American Airlines, TWA, and the rest, the tremendous

capital they have behind them testifies to their awareness that air freight is no small-potato

operation. A big business, air cargo cannot be started on a shoe string, any more than

a railroad.

GI's home from the wars deserve every break in the world. They should receive reliable

counsel on how to invest their savings. Those who know what they're talking about agree

that Vets should be told about air cargo as a post-war living - about its liabilities

as well as its assets.

Posted April 21, 2012

|