|

Flying Aces was

a unique aeromodeling magazine in that it devoted roughly half the pages to modeling

and half to full-scale aircraft, with a fictional action/mystery story included

as well. That was typical of the time for many magazines. I have really been enjoying

reading many of the non-modeling stories since they provide great insight into the

mindset of the country. These editions I have now come from the pre-World War II

era, so the focus is on America's preparation for entry into the Pacific, European,

and African theaters of operation. Many - if not most - people these days think

the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, suddenly launched us into

the war, but the reality is we knew involvement was inevitable and the

Military Industrial

Complex (so dubbed by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower)

was in full build-up mode by the time of the attack.

What Makes a Fighting Pilot?

If the answer to this puzzling question were known by any one man, he could command

a towering salary in any country. Since it is not known, however, we can give you

only a few requirements and case histories of men who had that unexplainable "something."

by Arch Whitehouse

Author of "We Must Build an Independent Air Force!" "Warplanes Pock Punch!" etc.

Major McGregor, left, inspects a group of U.S. Army Flying Cadets.

These fledgling flyers train for two years before they are listed as "regulars."

Probably the most interesting reading concerning the present war will be found

in the official Gazette notices printed in the better British newspapers and aeronautical

magazines. Few readers notice these items, set in small type, but in them will be

found all the color, drama, heroics, and tragedy of modern warfare. Those concerning

the activities of the Royal Air Force and its companion Fleet Air Arm are, of course,

the most interesting to those of us who follow the history of modern military aviation.

So far in this war, only five Victoria Crosses have been awarded to British sky

fighters in more than fourteen months of bitter fighting. In the last war, nineteen

were issued to airmen during the four-and one-half years of battle. Of these, twelve

were awarded to pilots of single-seater planes and for feats of individual courage.

The other seven went to pilots of two-seaters who performed outstanding acts of

gallantry in which the saving of their machines and observers was the highlighted

point of the citation. Among the single-seater pilots to get the coveted award were

such noted characters as Ball, Bishop, McCudden, Mannock, Hawker, McLeod, and famous

Zeppelin busters Warneford and Robinson.

The two-seater heroes you probably have never heard of. They were: Cap-tain J.

A. Liddel, Squadron-Commander R. Bell Davies, Sergeant Thomas Mottershead, and Lieutenant

F. M. F. West. No, you can't identify them. They were "merely" pilots of two-seater

planes and were not listed in the "ace" classification.

But what about the V.C. air . heroes of today? Who are they and how many planes

have they shot down in defending Britain?

A flight of RAF Blackburn Rocs soar in perfect step echelon.

Mr. Whitehouse says that gunners aboard these ships are potentially single-seat

fighting pilots.

Of the five awarded so far, only one has been issued to a single-seater fighter

pilot - a Pilot-Officer named Nicholson who lays no claim to a great victory list.

He was awarded his V. C. for shooting down two German raiders after his Hurricane

had been set on fire. He was badly burned, but he lived to tell the tale - and what

a story it was!

Then there was young Sergeant John Hannah, the Air-Gunner who fought a fire aboard

a Handley Page Hampden well inside Germany. Two other gunners jumped, but Hannah

stayed and somehow put the fire out with his gloves, a fire-extinguisher, and the

plane's log book. He even burned up his parachute in an effort to stop the forced-draft

blaze. He could have bailed out, but he decided to stop that fire if it was humanly

possible. His pilot got the bomber back safely-although no one knows why it flew

at all, or why it didn't break up in the middle where the fire had burned away many

of the important structural members.

Another modern V. C. is Flight-Lieutenant R. A. B. Learoyd who piloted a bomber

that carried out a successful attack on the Dortmund-Ems Canal. The other two are

a Pilot-Officer and a Sergeant Air-Gunner who flew a Fairey Battle against an important

bridge and destroyed it. They both died in the action.

Out of five new-war awards of the Victoria Cross, then, we find no fighting pilot

in the "ace" sense of the word. We do know, however, that there are several British

Spitfire pilots who have more than forty enemy planes to their credit. So far, though,

the best any of them can do is to get a Distinguished Flying Cross and, in exceptional

cases, a bar to their D. F. C. - which means that they have been awarded the same

decoration twice. But the Distinguished Flying Cross is at least two steps removed

from the V. C.

A glance through the Gazette list discloses that fighter pilots with twelve or

fourteen enemy planes to their credit are a dime-a-dozen. I notice, for instance,

that Pilot-Officer Albert Gerald Lewis, who bas eighteen Germans to his credit,

has received the D. F. C. and bar. Moreover, Sergeant-Pilots wit h the Distinguished

Flying Medal and at least a dozen enemy planes to their credit appear to clutter

up most Hurricane and Spitfire squadrons.

This all adds up to something new in aerial warfare. We must consider the fighting

pilot not only by his score against the enemy or the number of planes he has shot

down but also for his ability to carry out dangerous missions. Airmen who have been

able to consistently get good sets of pictures of enemy territory are being rewarded

daily with high decorations, whereas their "machines-downed" bag is comparatively

low. Pilots who can dare the anti-aircraft fire and go down low and get direct hits

on enemy bases are apparently worth more than the spectacular fighter - at least,

they are in Great Britain if the distribution of decorations is anything to go by.

A Fighting Pilot Must -

- be an excellent marksman. This can be developed only

through handling firearms and is not something that

might be called a "gift."

- have a clear mind at all times and be able to

reason thoroughly during combat with an enemy.

- be a natural flyer and have a real love for aviation.

- have fear. Courage is for the usual run-of-the-mill

flyers.

- be quick in making decisions. He should know

what is the right maneuver instead of hoping it is right.

- have respect for the enemy. This is probably

the most important item.

But we must have fighting pilots, whether they win decorations or not. Without

the fighting pilot, the bombers and reconnaissance ships would find it extremely

difficult to carry out their all-important missions. The fighter pilot must first

gain command or control of the air before the bombers and reconnaissance machines

can dare to take-off and attempt to raid or photograph the enemy.

The failure of the German Air Force to "break the ground" for the invasion of

Great Britain has been due mainly to the fighting superiority of the British pilots.

The planes themselves have nothing to do with the situation. Germany has had more

ships than the British ever since the war began. However, the British youngsters

have out-fought the Nazis from every angle. When the Germans rain bombs on London,

they usually make the most of the darkness of night or clouds during the day. When

they have dared daylight raids without benefit of cover, they have always been severely

beaten back by the pilots of the fighter command. That is why almost all of the

Nazis' heavy bombing is undertaken under the cover of darkness.

British bombers also wisely make the most of night and clouds when they raid

important German points. They are different from the Nazis, though, in that they

have splendid aerial gunnery defense. The young Air-Gunners aboard bombers are,

of course, all potential fighter pilots, just as many aerial gunners of the last

war became skilled single-seater fighter pilots.

It is obvious, then, that if we are to have an Air Service capable of taking

care of itself and carrying out the duties for which it was intended, we must first

of all develop fighter pilots. Whether these men fly Lockheed, Bell, Curtiss, Republic

fighters, Douglas observation planes, or Martin bombers, they must be first and

foremost "fighting" pilots. No matter what their duty, they must be fighting men.

Learoyd, Hannah, and Nicholson were all fighting airmen, in that they did not give

up the battle until the end. Yes there's a great deal of difference between a fighting

pilot and the studious engineer type who flies our airliners across the continent,

guided by radio beams and a ground staff of hundreds.

"Any military pilot - whether he is aboard a pursuit or a patrol

amphibian like this Consolidated PBY-5A - is a fighting pilot," says our author.

But where are we to get the American equivalent of Hannah, Learoyd, and Nicholson?

These men are not "types." They are, according to their pictures, as unalike as

three men could be. As an example, we only have to go through past history and look

over the faces of the men who made American aviation history in 1917-18.

There were no particular types even then. They were typical Americans, yes, but

far from being special "types." They didn't even look alike. Rickenbacker was a

cold, calculating figure. Luke, wild and demonstrative. Joe Wehner, a slight, cheerful

chap. Bill Thaw, heavy and colorless. Dave Putnam looked like a high school boy.

James Norman Hall, dour and thin-lipped. Raoul Lufbery, rough and gruff. You go

through the rest yourself and see what I am getting at. They might be grouped together

and offered as the tenth Class Reunion of the Eighth Grade of Public School No.

15 in any town in the United States.

But above all, most of these men were volunteers. Many of them had crossed the

Atlantic to take up the fight against what was called Prussianism long before the

United States entered the war. There can be no out-and-out volunteers today, except

that small handful of men who are now training to fight with the British. Conscription

and the Selective Service System have done away with the old type of volunteer,

although there are still many who joined up long before the draft system was put

into operation.

The volunteer, as we knew him in the last war, hardly fits the series of present

conditions because of the vastness and mechanics of modern warfare. The old soldier

of fortune, whose chief stock in trade was the knowledge of a Springfield rifle

and a Maxim machine gun, would today be lost in the intricate maze of mechanical

and chemical warfare.

The instructor in a training plane knows how his student is progressing,

but he doesn't know how he will be when under heavy enemy fire.

The fighting pilot of today and tomorrow will be a combination Frank Merriwell

and Thomas Edison. He will not necessarily be a renowned college athlete, a two-fisted

fighter of the fiction world, or a Charles A. Lindbergh. I venture to hazard a guess

that the greater number of American fighting pilots will come from the suburban

or rural section of the country. There we find youngsters who are more than familiar

with bicycles, motorcycles, automobiles, and tractors.

The youngsters from the rural districts are as much at home with a tractor or

a big bull-dozer as the city boy is with a pair of roller skates. Intricate farm

machinery such as binders, milking machines, harvesters, power saws, hay loaders,

and road scrapers are as familiar to him as the knife and fork he uses at breakfast.

And with all that, he still goes to high school and college. He repairs automobiles,

radio sets, pumps, tractors, and sets up his own power plant, either in a local

stream or on top of the barn where he harnesses the wind to a dynamo propeller.

The writer has had ample opportunity to study these youngsters in the past six

months, having moved to a very rural district in New England where he has discovered

that the country boy is no longer the dull hick of song and story. The country boy

of today is the most suitable material for the modern mechanized Army. He is acquainted

with firearms of all kinds and handles them well. You never hear of hunting and

shooting accidents among country boys. The city sportsmen bring their accidents

to the country.

But while the country boy is apparently most suited for modern warfare, it is

also a fact that he does not generally care for aviation. This is another point

the writer has learned in his few months of living in an old New England village

and getting acquainted with the youth. It is startling to note how little interest

there is in either commercial or military aviation. But few of the old World War

aces did, either, until the war broke out.

The strange thing about this business of seeking material for our air fighting

forces is that there is no set rule about it. Education and environment apparently

have nothing to do with it. Knowledge, of planes and engines has nothing to do with

it. The ability to fly well, moreover, has nothing to do with a man becoming a great

air fighter. All he really has to know is how to get his plane off the ground and

get it back again. The writer was personally acquainted with several of the better-known

aces of the last World War. In most cases these individual fighting stars were not

great airmen in the accepted sense of the word. If the truth be known, they became

aces because they were allowed to carry out individual offensive patrols as free

lance pilots, because they were not suitable to fly in tight formations! I believe

I have gone into this angle before, and there is no use in taking up valuable space

to outline the individual cases again.

My readers will perhaps argue that those with superior education will make the

best fighting airmen. I can only point out that Great Britain's RAF is composed

by a great percentage of non-commissioned officers; men who have risen from the

ranks to become Sergeant-Pilots, Air-Gunners, and Observers. These men are not the

university group. They are representative of the class that gets through grammar

school and possibly gains about two years of high school education. Many, moreover,

have considerably less.

The modern fighting pilot can he taught to handle, without a college education,

practically any type of military plane. This has been proven time and, time again.

But, as I have pointed out before, the university man makes a better officer and

is more likely to be able to assume the responsibility of command. Air fighting

ability is one thing and the courage to take high rank responsibility is quite another.

It is an actual fact that, except in rare instances, the greatly publicized aces

of the last World War were pathetic as squadron leaders where they had to do paper

work and make quick decisions on the ground. In the air against an enemy opponent,

they were supreme - but the responsibility of squadron leadership demanded bravery

and courage of another classification.

We are likely to mistake mechanical and aeronautical knowledge for fighting ability,

whereas these qualifications have nothing to do with fighting courage and fighting

skill. Major Jimmy McCudden used to say: "No matter how much you know, you can't

get out at 8,000 feet and clean a distributor."

Mechanical knowledge quickly helps in training our fighting airmen, but it will

not assure us that he will stay in a fight and score victories or go through with

a mission against great odds - or heavy gunfire. You may know every nut and bolt

in a Twin-Wasp or an Allison, but what do you know about a bulged cartridge jam

in a Browning machine gun?

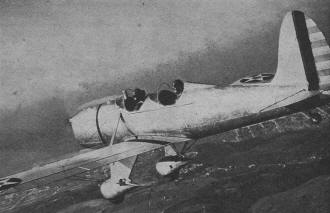

If the fledgling in this Ryan PT-20 has the necessary qualities,

he will be a great we pilot. If not, he'll be an out-end-out dud.

It is strange, but the quiet, unassuming choir boy makes just as good a fighting

pilot as does last year's All-American quarterback. They both have a certain quality

of courage which somehow asserts itself in the air. The same two might become quaking

cowards in the gun-sponson of an Army Tank. Look at Albert Ball, Rhys-Davids, Alan

McLeod, Reggie Warneford, George Vaughn, David Putnam, and Georges Guynemer. They

were all kids in every sense of the word-and I like to call them the choir-boy crowd.

But look at what they did and what they accomplished in the air.

It is obvious, then, that there are no marks on anyone to indicate whether he

will become a great fighting pilot. No matter how good they are at flying school

or in the classroom, you can never tell how they will turn out when the guns begin

to boom. Many times during the last war I heard people say: "I certainly never thought

he would ever become a great soldier. Why, he would never even take a dare! He was

always reading books and he never made one athletic team in high school. How can

you figure that?"

Perhaps it is fear that makes great airmen, not courage - the quality of fear

that turns them into raging madmen when their life or safety is threatened. I am

quite sure that Sergeant Hannah more feared the prospects of being taken prisoner,

had he jumped from that Handley Page Hampden, than that of burning to death or crashing

in a flaming bomber with no parachute to save him.

The writer, who spent many months in various capacities on the Western Front

with the Royal Air Force, can still recall the clammy sensation of fear that came

when an engine began to falter miles over the enemy line. The same fear never arose

when enemy planes attacked our machines. All of us agreed time and time again that

it was the fear of being shot down and being taken prisoner that made us put up

our best efforts. We feared being confined behind barbed wire and subjected to the

indignities of a prison camp.

Flying Cadets A. L Nelson and V. K. White inspect a North American

BT-9. Will they become ace flyers? No one can tell until ...

What does all this add up to? We are trying to determine what makes a great fighting

airman, and so far we have not found an answer. If I could look at any group of

men and say definitely that this fellow and that fellow would be top-notch, then

I am sure I could command a towering salary in any country. As a matter of fact,

it's even impossible to tell this during the training or peace-time service stage.

The officials of the Army Air Corps and Navy Air Service draw up a certain physical

and educational specifications to which candidates must conform. Then they demand

that the Cadets undergo certain ground and air training. At the end of two years,

we have a graduating class of military airmen - but we have no idea of how they

will perform in actual war. They may be great at aerobatics, navigation, theory

of flight, and gunnery, but all that goes by the boards when the enemy's guns begin

to spit. /p>

With all this, though, there are still fundamental qualities necessary to become

a fighting pilot. Some of them don't show for quite some time, and others are apparent

immediately. But, regardless, every real fighting pilot should be an excellent marksman.

This can be developed only through handling of firearms. It is not something that

might be called a "gift." He must at all times, during a battle, have a clear mind

and be able to reason thoroughly. Even though some of the World War pilots flew

into a blind rage during the heat of battle, the greatest aces were always composed

and they usually had their actions planned long in advance.

A fighting pilot need not be an airman in the strictest sense of the word - that

is, it's not necessary for him to know how to land on three points every time and

how to come to a stop within so many feet. He must be a natural pilot, however.

There is a great deal of difference. In the air, a natural flyer will always fly

rings against one who "just wanted to learn."

And, as you have undoubtedly gathered by now, a truly great fighter must have

fear. Courage is for the usual run-of-the-mill pilots who "just don't give a damn."

If you have fear of being captured, for instance, you'll move heaven and earth ten

times a day to keep that from happening.

And now we come to the most important item - one that is never taught but has

to be learned through experience. That is - respect your enemy. Respect his flying,

his machine, and the cause for which he is fighting. Remember, he is just as good

a man as you are, and he might be better. Don't underrate him during combat, because

you may be overrating yourself. Instead, feel him out, cautiously, and determine

exactly what type of an airman he is, how he flies, whether he is a good marksman,

and whether he can think as rapidly as you.

Beyond that, there is nothing more that can be said. True, various causes made

many World War aces the great flyers and fighters they were - causes which we undoubtedly

will never know. However, the above listed are the basic principles - and maybe

that's the reason there are so few real fighting pilots.

Posted September 20, 2015

|