|

In 1974, I was flying some of my first R/C

gliders - probably a Mark's Models Windward

or maybe the Windfree (in that order). During

that time, I tried hard to locate a group of sailplane flyers in my area around

Mayo, Maryland, but to no avail. The nearest R/C flying field was about 30 miles

away in Upper Marlboro, MD, where the PGRC

club field used to be. My family's car was held together with chewing gum and bailing

wire, so it wasn't often that I could talk my father into driving me out there,

and the few times that he gave in to my whining, there were never any gliders present.

When I would see articles like this one on the Fifth Annual R/C Soaring Nats in

the October 1974 issue of American Aircraft Modeler magazine, my envy level

would increase significantly both from the standpoint of way-cool models and R/C

equipment (I had second-hand junk, purchased with newspaper route money), but also

because of the people lucky enough to have access to such venues.

Fifth Annual R/C Soaring NATS

By Patrick H. Potega

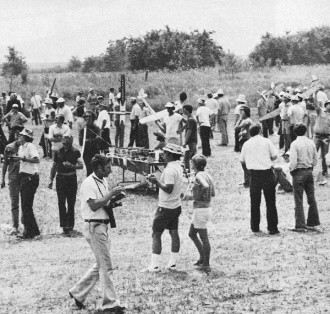

With 175 contestants, the 1974 Fifth Annual

RC Soaring Nats was the largest flatland soaring con-test ever held in the world

- approaching the gigantic get-togethers at Kirchheirn-Teck, Germany. Three days

(July 22-24) of varying weather at the contest site (Lewis College, Lockport, Ill.),

and varied landing conditions made this competition for Grand National Champion

a true test of both plane and pilot. With 175 contestants, the 1974 Fifth Annual

RC Soaring Nats was the largest flatland soaring con-test ever held in the world

- approaching the gigantic get-togethers at Kirchheirn-Teck, Germany. Three days

(July 22-24) of varying weather at the contest site (Lewis College, Lockport, Ill.),

and varied landing conditions made this competition for Grand National Champion

a true test of both plane and pilot.

The magnitude of such an event would seem to dictate Pentagon-style logistics,

yet the manpower behind this Nats has always come from a handful of dedicated members

of one club - S.O.A.R. (Society of Aeromodeling by Radio). Their organizational

capabilities were immediately apparent July 21 as registration (pre-registration

is an obvious prerequisite) took about one minute per contestant.

This left plenty of time for the inevitable conclaves of sailplaners to gather.

Friendly handshakes in this corner, a heavy discussion of aerodynamics nearby, a

rules debate over there, while others wandered off singly to psych themselves up

for the task of flying three flights on each of the next three days.

Throughout the contest, one topic seemed to dominate each group - the formation

of the National Soaring Society. (The outcome of all these discussions can be found

on page 12 of this issue of AAM).

Vintage scale Ibex glider.

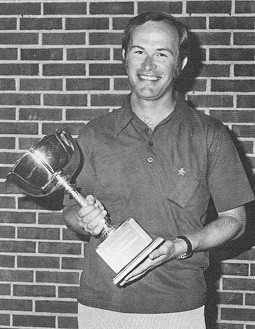

Otto Heithecker, 1971-1972 and now 1974 Grand National Soaring

Champion, with his Best Design-winning Challenger II.

"Otto Von Helium," as his new sobriquet affectionately dubs him,

shows the landing technique that made him Champ. Lots of talking to the plane and

plenty of body English.

Mark Smith (Mr. Windfree) took Standard Class Cumulative 15-Minute.

Dave Shadel was runner-up to the Grand Champion. Dave is one

of this year's most advanced fliers.

Rod Smith received the perpetual "Willow-Bee" Thermal Wand from

last year's recipient, Tom Kelly.

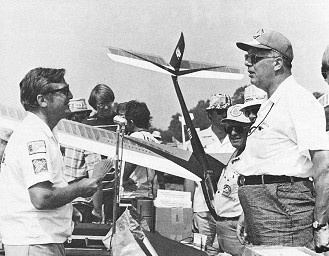

John Nielson (right): "Mr. Contest Director, I should very much

like to give Mr. Kelly here more points because his airplane is so pretty." Dan

Pruss (left): "As CD, all I can say is no. As CD, all I can say is no. As CD, all

can say ....

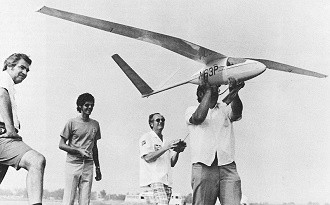

Gordon Pearson launches into a flight that lasted almost six

minutes. Who says scale sailplanes can't perform?

The three scratch-built entries in Scale. From left to right,

Gordon Pearson's Ibex, Max Geier's Grunau Baby and Doc Hall's SG-38.

Max dramatically reciprocates with a super launch of Doc's SG-38.

Doc Hall captured third in Scale with the exquisitely detailed

SG-38.

Turnabout is fair play. Doc Hall launches Max Geier's Grunau.

The Soaring Nats maze - how to get from the winches (off camera

left) to the landing circles (off camera right) without loosing your model, breaking

someone else's, or just plain getting lost in the crowd.

Hugh's Stockpile (ugh!). Soarcraft's Hugh Stock with just a few

of the scale models built from his superb kits.

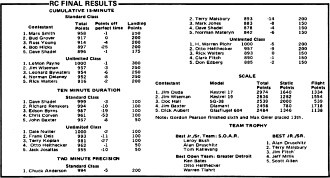

5th Annual R/C Soaring Nats scoreboard.

Monday morning came too soon for most of those who caucused into the small hours.

Bleary breakfast eyes reflected the bleak weather on the field. The clatter of 7

o'clock coffee was disrupted by the announcement that the first round would be delayed

until 10 a.m.

The interim hours were well spent scrutinizing the handiwork of scale on static

display. With some 18 entrants (15 of which flew), Scale has had an 80% entry increase

in one year. While only three models were scratch-built from plans, the general

quality of workmanship on all entries was tremendous. Doc Hall's SG-38 immediately

impressed the spectators (and later the judges) as a tour de force. With scale rigging

and flawless workmanship, this 90" version of a German primary trainer was complete

even to the scale working landing-skid shock absorbers.

Max Geier's Grunau Baby also captured the flavor of antique scale. This year's

entry was a 50% enlargement of last year's Grunau (which tragically crashed because

of its unwieldy stability on tow). The new Baby showed more refinement and attention

to detail.

A surprising entry (surprising in that it was the only scratch-built model that

attempted to come to terms with building a scale model of a modern sailplane) was

Gordon Pearson's Ibex. Modeled after Stan Hall's unusual V-tailed and gull-winged

experimental homebuilt, it was impressive in not only its 147" span, but also in

the completeness of interior cockpit detail (about all we can really detail on a

sailplane, one would surmise, is the cockpit). Grossing in at 138 oz., the model

featured operational ailerons (many entries used striping tape to simulate ailerons),

flaps, full-flying V-tail, and operational water ballast.

The remainder of the field were, while excellent individual technical achievements,

scaled versions of kits. Almost exclusively Soarcraft designs, these Glasflugel

604s, Libelles, Kestrels and Diamants were a strong index of today's norm in sailplane

scale. Jim Duda's Kestrel 17, and Hugh Stock's Diamant showed that an out-of-the-box

model can hold its own in scale. This is even more apparent when one realizes that

the rules give 50% of the total score for static points, and 50% for flight points.

And these Soarcraft sailplanes are miniatures of full-scale, high performance soarers;

i.e., they can usually hold their own with any Unlimited Class model.

Eventually, people drifted away from the fascination of scale to the wet reality

of the flying field. Tents were pitched, winch lines run out, and models assembled

- all in a steady, seemingly unabating shower. Like aquaphobes, the contestants

sheltered under canvas and waited ... and waited.

Ten o'clock passed like just another rainstorm on the dark horizon, and the view

from beneath the tents changed little, although the wind did. A shift in wind direction

is one of the ultimate nuisances of any thermal contest, but at the Nats it's a

royal pain to move eight winches. It took about 20 minutes to accomplish this -

during the only hiatus in the showers all morning. After relocating all the vehicles

and tents, the contest settled back into the same routine ... wait for the weather.

Finally, at 1: 11 p..., the first flight was launched in the Cumulative 15-Minute

task (this event must be flown to completion, since partial scores are meaningless).

The first three dozen or so flights were in relatively good air, with many maxes

(7 min.). As the round progressed, the ceiling began to lower and flight times went

sour. Near the end of the round, the sailplanes were literally launching into the

ever-lowering clouds, and the average times dropped into the 3- to 4-minute category.

Much to the credit of S.O.A.R.'s strategic planning, the first round took only 2

1/2 hours to complete.

Two-Minute Precision was next. This task goes very quickly, so there were high

hopes of getting at least two flight scores on the boards that day: In this event,

some of the contestants got their first real taste of a spot landing within the

three-ringed bull's-eye (10, 25 and 50'). This was a logical change from last year's

164 x 8' runways, since the circle permits a landing from any wind direction.

To the dismay of many, the wind did shift, but all the way around to 180°

of the launch direction. About halfway through the round, pilots were coming in

over the flight line to zero-in on the spot. Even worse was trying to get a decent

launch downwind in a 10-15 mph breeze. CD Dan Pruss decided to stop the day's activities

about halfway through the round (thank goodness, since I was next to launch with

that ever-increasing tail wind). All scores were dropped and flying was scheduled

to begin again the next morning, with hopes of squeezing in extra rounds during

the next two days. With only one score posted, the Nats was still a wide open contest.

Tuesday morning's coffee was much sweeter because of the improving weather. At

8 a.m., Two-Minute Precision was the first task up the towlines.

With the landing circle set up about 75 yards upwind of a tree line, the first

pilot was duped by the 12 mph winds and landed in the branches. Many more were to

follow, and it became obvious that the smaller landing targets were separating the

men from the boys. Many who made it into the landing circles got dumped by the winds

and lost points for coming to rest inverted. The "javelin" landers were especially

prone to this, since they would come in hot and impale their gliders with full down

elevator, only to have the wind get under the wing or tail and unceremoniously defeat

all their efforts.

During the Two-Minute task, many models were encountering noticeable lift, and

by the next round (part 2 of Cumulative 15 Minute) hopes of good flights abounded.

There was enough wind so that many maxes were achieved by flying over the nearby

buildings, and using the small patches of mechanical lift to sustain flight. Thermals

were obviously present, but they were patchy and moving downwind, away from the

field, fast.

I was elated to find myself in the enviable situation of having Otto Heithecker

(1971-72 Grand National Soaring Champ) launching on the winch adjacent to mine.

Anticipating the piggyback strategy, I went up only seconds before the man who seemingly

never misses a thermal. I went out over the buildings and loitered, waiting for

my free ticket to a max to join me in the air. I flew through what seemed a nice

thermal, but decided to wait for the pro to find me a better one.

Four-and-a-half minutes later I landed, with still no sign of Otto (one Nationally

known flier nicknamed him Otto Van Helium, since he always seems to go up). When

I looked skyward, there was Heithecker's Challenger design, at least a half-mile

downwind and way up. The bump I had flown through had apparently been picked up

by him somewhere behind my field of vision, and he had ridden it to a max. Seeing

his model further away than most fliers would ever dare venture was the whole story

of why he had twice been crowned National Champion. To the surprise of many, Otto

missed his spot landing - a rare occurrence indeed.

The day was shaping up nicely, with reasonable cumulus cloud build-up generating

some fair thermals. The Ten-Minute Duration task seemed a real shoo-in, but many

were to find that wherever there is lift, downer must follow. In any contest where

launching at a predetermined time is mandatory, the luck of the draw plays a role.

Getting one 10-minute thermal flight would usually put the odds in your favor, but

not if the only thermal you catch is during the Two-Minute task. Having the contest

spread over three days, and rotating the launch sequence gives everyone a reasonable

chance.

While munching on a mammoth chunk of watermelon, supplied in quantity (a whole

boat full) by Jerry Nelson and John Osborne of Midwest Model Supply, I thought how

it never ceases to surprise me to see sailplanes fold wings. I was flying a Cumulus

2800 (my first and second ships met disaster during the two weeks prior to the Nats),

so I was safe on the score of seeing a wing buckle on the tow. Yet many models augered-in

after losing a bout with the winches. This year, the winches seemed relatively mild,

so that one can only speculate as to why more attention isn't given, by designers

and builders, to the integrity of the center section. Maybe someone will design

a wing center panel that has good flex and light weight, but will never fold.

Even more important, I thought, as I dribbled watermelon down my chin, should

be an attempt to standardize winches, so the pilot can anticipate the torque and

speed which will develop. It is hypothesized that part of the problem this year

was that the winches were too slow, thus forcing fliers who were hungry for altitude

to try more up elevator and do less pulsing. Throw a wind gust or thermal into this

situation and you have a mylar bag of balsa.

Scale flying was the final order of the day. John Baxter was one of the first

off the line. He flew into some beautiful air and grabbed an easy 10-min. max and

spot landing. Doc Hall's SG-38 brought an immediate round of applause from the crowd

as it towed up the line as stable as a long-tailed-kite. He achieved a 53 second

score, which is lousy for the contest rules, but very much in keeping with how the

full-scale design would stack up to today's 20:1 glide ratio super sailplanes.

While the Libelles, Diamants, etc., put in high flight times (this "class" of

ship averaged 4:20 for the first round), the three scratch-built projects were getting

maximum points for spectator appeal. Geier flew a 1:05, while Pearson did a fantastic

job, flying his Ibex for 3:13 (not too surprising, considering that the model has

the same airfoil as a Grand Esprit). Pearson was one of only four fliers to make

a spot landing.

The Two-Minute Precision event for scale showed everyone on a relatively even

basis. Most of the times were very close to those in the Unlimited Class. Even the

spot landings were good, with eight spots hit, and two of these perfect 100-pointers.

Wednesday morning's coffee was either bitter or sweet, depending on what sort

of score you pulled the previous day (mine was absolutely undrinkable). As I watched

others go back for a second cup (obviously the winners), I noted the day's wind

direction and landing locations. This Nats offered a complete variety of conditions

for both thermal activity and landing terrain on each of the three days. Today,

it would be hot, with lots of cloud formations and good lift.

During the first round (Two-Minute Precision), most of the fliers' attention

was focused on the scoreboard. Perhaps because only four flight scores had been

posted, instead of the usual six, the pack was really close at the top of the pile.

Anyone of some 10 to 15 fliers could become Grand National Champion.

Jeff Mrlik, last year's Champion (see August AAM) was off his stride, with a

5:49 for his first 10-minute flight and several low landing scores. Heithecker looked

good, but certainly not invincible, due to a zero on one landing. There was simply

too much flying yet to come to make any predictions.

The Two-Minute Precision task was made doubly difficult because the landing circles

were on ground made slippery by moisture and dew. Come in a little hot and you found

yourself skipping or sliding out of a good landing score.

By the time the Cumulative 15-Minute round started, the air was surprisingly

buoyant, and columns of piggybacking sailplanes were a common sight. There were

periods of terrible down air, during which the hopes of a few were dashed as they

landed short of their target times. The same conditions held for Ten-Minute Duration,

yet many found themselves walking away with only 3- to 4-minute flights - Lady Luck

was really doing her thing.

Even after all the rounds were flown, the real winners were still a mystery.

Since the day's scores weren't posted, no one could even speculate. Only at the

awards ceremonies that evening would the final outcome be revealed. However, conversations

around the trailers and tents gave a few hints as to the possible outcome. Dave

Shadel of California was only a total of three seconds off on his Ten-Minute Duration,

while Dale Nutter was only two seconds off the mark. Mark Smith looked really good

in Standard Class Cumulative Duration, only one second off a perfect flight. Bud

Grover had phenomenally flown three flights for a perfect 15-minute total, but he

was off on one landing. LeMon Payne hit three flawless spots and was only one second

off exactly 15 minutes.

The times in Two-Minute Precision were somewhat surprising, since no one was

exactly on. Warren Plohr was off by two or three seconds in Unlimited Class, while

the best shot in Standard Class was Chuck Anderson, who had one perfect flight,

but was a whole eight seconds off in his second round.

These concerns were lost as the scale boys prepared to fly their final rounds.

The air was really up, and the high performance designs grabbed good flights. Gordon

Pearson shocked everyone by keeping h is Ibex up for nearly 6 minutes - a very creditable

performance. Max Geier, who had first flown his Grunau Baby the Saturday before

the meet, was down in less than 2 minutes. Doc Hall's SG-38 was pitiably short of

the required 10-minute max. But how could models, scaled after planes which were

heavy and inefficient, be expected to thermal like the super sailplanes? All the

scale fliers are to be commended for doing such a fine job of competing with planes

which, two years ago, would have seemed impossible to fly.

With the last scale flight, the '74 RC Soaring Nats were ended, except for the

banquet and awards presentations. The banquet was highlighted by the gracious and

humorous hosting of John Nielson, S.O.A.R.'s master of ceremonies. All eyes were

on the presentations table, which literally overflowed with nearly 50 trophies and

awards.

Talk around the tables was that Otto Heithecker might have just missed the Grand

Champion Award. Dave Shadel, it was conjectured, might have slipped through and

nipped Otto. Perhaps that one landing that Heithecker had missed would be his undoing.

A highly important new trophy was added this year. The Felix Pawlawski Memorial

Trophy, donated by the University of Michigan Dept. of Aeronautical Engineering,

was presented to the Junior/Senior who scored highest on a written quiz. The award

strives to foster Junior/Senior achievement toward a career in aeronautical engineering.

(See page 50 of this issue of AAM for the quiz and the young man who won it.)

Everyone waited breathlessly as the other trophies were called out. Dave Shadel

took a fifth in Cumulative Duration, a first in Ten Minute, and a fourth in Two

Minute. Heithecker on the other hand, accumulated a second in Two Minute and a fourth

in Ten Minute. Perhaps Shadel, flying a Standard Class sailplane, had done it after

all.

Finally, only the three Grand Champion trophies remained. Terry Koplan of California

came in third, then Shadel's name was called. A huge round of applause arose from

his fellow competitors as Otto Heithecker was crowned Grand National Champion for

the third time. Heithecker's Challenger II design won the Best Design Award. Chet

Lanzo was presented with Best 'Technical Achievement honors for his Ascender Self-Launch

System.

Other special awards were the President's Award, given by Johnnie Clemens to

Dave Burt of S.O.A.R. for his exceptional services to aeromodeling. As if three

trophies and a $300 Schwinn bike weren't enough, Otto Heithecker also was presented

with a singular award - a bag of sand (for sandbagging before launch in order to

get better air), and a power pod (to get him out of silent flight). In the same

light vein, Rod Smith of Mark's Models was given the notorious "Willow-Bee Thermal

Wand" - a perpetual trophy intended to help the bearer detect thermals and win contests.

For the sake of space, other winners and their scores are listed below.

The conclusion of the S.O.A.R. Nationals was a round of applause for the group

of dedicated people who made it all possible. Next year, the country will have a

chance to see if the Soaring Nats can be held without the hard work of the members

of S.O.A.R. One thing for sure, this club has set a precedent in contests that will

be almost impossible to duplicate. It is befitting that the last S.O.A.R. Nats was

the biggest and best thermal contest anywhere in the world.

Posted February 14, 2024

(updated from original

post on 8/23/2014)

|