|

Peter Bowers

first became know to me because of his Fly Baby homebuilt airplane. It won the Experimental Aircraft

Association (EAA) design contest in 1962. Back in the middle and late 1970s, I was

taking flying lessons and dreaming big about building my own aerobatic biplane.

Being an avid woodworker, the Fly Baby appealed to me because it was constructed

entirely of wood, except for a few critical metal fittings. My plan was to build

the biplane version of the Fly Baby. Like so many other things, the aeroplane never

got built. Peter Bowers was not only an aeronautical engineer and airplane designer

but also an aviation historian and model airplane enthusiast. This article from

a 1957 edition of American Modeler magazine is an example of his endeavors.

Aeronautical Antiques

Author Bowers flys steel-tube replica of 1912 Curtiss built in

'47 by Waller Bullock (now owned by Ed Weeks, Des Moines).

By Peter M. Bowers

Not all antique hunters who poke around in old attics and barns are looking for

Duncan Phyfe furniture or Paul Revere silver. Some, thanks to the recent surge of

interest in vintage aircraft, are snooping for an old Jenny, or at least a Heath

Parasol.

This is not just a random undertaking on the part of a few individuals. Interest

in old airplanes is worldwide, and is encouraged by several formal organizations.

Oldest is the Vintage Airplane Association in England; best-known here is the Antique

Airplane Association, formed several years ago by Robert L. Taylor, with headquarters

at 429 North Market Street, Ottumwa, Iowa.

As the organization grew rapidly, it was soon issuing a monthly publication on

slick paper to replace an original mimeographed bulletin that had kept the members

posted.

|

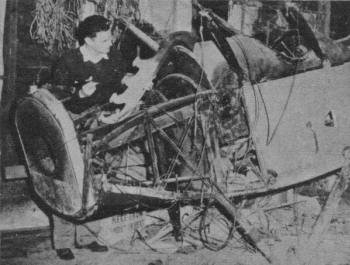

Pete inspects old Jenny.

Note condition of Heath Parasol when he acquired it along with

spare Szekeley.

|

In 1955, the AAA polled its membership to determine just what age should qualify

an airplane as an antique. The response was overwhelmingly in favor of a calendar

age of twenty-five years, which is short by antique furniture standards but positively

venerable when considering that aviation itself is barely fifty years old.

This arbitrary line of demarcation brings up problems of its own, as in the case

of one basic airplane design built over a period of years divided by the line. A

Fleet Model 2, built in 1929, qualifies as a genuine antique while a near-duplicate

Model 16, built in Canada early in WW-II, does not. Actually, it is the configuration

of the airplane, rather than its actual year of manufacture, that appeals to the

collector and establishes the antique classification. No one would hesitate to call

any of the wire-braced Aeronca C-3's built between 1931 and 1936 an antique, but

they would think twice before calling a Douglas DC-3 an antique even though that

model was introduced late in 1935.

Antique airplanes fall into two general classes-those that are rebuilt and flown

by their owners strictly as a hobby or for sentimental reasons, and those that are

workhorses doing a job that more modem equipment cannot do as well. In the first

class will be found the purely sporting models such as the Heath Parasol and Pietenpol,

other home-builts, and the smaller training and personal types like the Fleet and

the Taylor Cub. A few World War I and earlier designs are included.

The second class is made up mainly of ships that still have relatively high commercial

value, or that are too heavy and expensive for the average private owner to maintain,

and includes most of the Travel Air biplanes, still widely used as sprayers, the

Ford Trimotors, for which a suitable replacement has yet to be built, and most of

the four-to-six-place cabin monoplanes of the late twenties and early thirties that

are still well suited to mountain flying and other short-field work. These models

are too valuable to be kept off to one side as a hobby even if their owners could

afford to do so.

Before dealing with the question of where these old airplanes come from, mention

should be made of two places where they do NOT come from, both of which are dead

ends enviously eyed by the old airplane fans. Most of the real old timers are in

museums, sometimes on display but more often in storage due to lack of suitable

space, and fortunate indeed is the collector who has been able to obtain one from

this source by purchase or trade.

Two collectors, Frank Tallman of Glenview, Illinois, and Cole Palen of Poughkeepsie,

New York, managed to score phenomenal successes in this direction by buying out

private museum collections. Tallman bought four of the six WW-I types remaining

in the J. B. Jarrett Museum of World War History, and Palen obtained several World

War I types and a prewar I Bleriot that used to be in the Aviation Museum at Roosevelt

Field, Long Island. These are exceptional cases, however, and the museums were private,

rather than public, institutions.

|

1931 Razorback Aeronca C-3 owned by P. B. 1934-36 Aeroncas with

altered fuselage and cabin also called C-3s.

Thomas-Morse S-4C owned by Paul Kotze still uses the tricky rotary

engine which went out of production at end of WW-I.

Pietenpol "Air Camper" powered by converted Model "A" Ford engine;

owned by Allen Rudolph, Woodland, Wisconsin.

Oldest production sportplane in U. S. is 1919 Ace powered by

40-hp water-cooled Ace engine. Rebuilt by Lorill Lowrey.

Single seat 1930 Buhl Bull Pup with 45 hp Szekeley engine. Several

modified with new motor, cut-down Luscombe panels.

|

The other dead end is Hollywood, where an intriguing variety of antiques dating

back to WW-I is used for motion picture work. About the only way to obtain one of

these is to have some other antique that happens to be in urgent demand at the moment.

Thanks to a number of recent movies that required the use of specific airplanes,

a certain amount of antique swapping has been done by Paul Mantz, undisputed leader

of the Hollywood Stunt Squadron for over twenty years, and owner of the largest

private collection of flyable or restorable antiques in the country.

Ordinarily, one would think that the place to start looking for old airplanes

would be around an airport, but such is not the case. Of course, there are some

old relics hanging in the rafters or stuffed in the corner of the shop, but most

of the old timers that can be found at an active airport are owned by people who

want to keep them, Storage space at an airport comes high, and is not likely to

be occupied by some forgotten hulk that the owner doesn't want.

Logical place to look for a long-stored airplane is in a place where it is out

of the way and where the space does not cost the owner or his heirs anything. Old

barns in rural areas where farmers used to fly their own planes back in the license-free

days provide good hunting, while logical places to look in cities are in the rafters

of garages and machine shops. Owners or employees of such places would have had

better-than-average qualifications for building or restoring airplanes as a hobby.

The author recently obtained a 1930 Pietenpol Air Camper that had been stored in

a machine shop since 1937.

Other sources of old aircraft, especially military models, are schools, from

high school through college, that have, or used to have, aeronautical courses. In

the years between World Wars, and again after WW-II, the government gave many surplus

aircraft to such organizations for classroom use. Many were broken down into parts,

or otherwise cut up, but some were left intact.

Major difficulty involved in obtaining one of these types when it is found is

the fact that most of the government gifts had a string tied to them - the school

was prohibited from selling them or using them for other than educational purposes.

There have been numerous cases in recent years where schools have junked their older

relics after obtaining more modern replacements merely because they could do nothing

else with them.

A glider pilot friend, Ken Hovik, visited a home in Everett, Washington, one

day to hang some venetian blinds. He noticed a picture of an old glider on the wall,

and arranged to come back on his own time to talk to the owner, since he was interested

in such things. During the course of the ensuing conversation, the former glider

owner mentioned the presence of the old Pietenpol in a nearby machine shop. Ken

took a look at it, found that it was available, and told the author, who contacted

the trustees of the late owner's estate and arranged a purchase.

In a way, this is a typical case, where several people interested in old airplanes

had driven within a block of this plane for years without realizing that it was

there. The really lucky part is that the plane was "Found" just in time, for the

contents of the shop were being disposed of at the time, and the wooden airframe

was slated for the bonfire.

People who are searching for a specific type are seldom so lucky, but a few succeed

after phenomenal demonstrations of patience. The more specific the collector's desired

plane, the more frustrating his search can become. The most desirable, and of course

the hardest to find, are genuine World War I types. There are roughly one hundred

of them in the hands of museums or private owners today, and it is conservatively

estimated that as many more are still hiding out in barns and basements, unknown

to the collectors and virtually forgotten by their owners or their surviving families.

This is one of the great tragedies of antique airplane hunting. Many of the non-aviation

people who do come across an old airplane think that it is of no use to anyone,

and destroy it as a worthless piece of junk. Such was the case with a Spad in eastern

Washington. An old farmer who had owned it had refused to sell it to the few aeronautical

people that knew he had it stored in the barn. It had been his old ship, and he

was sentimentally attached to it. The farmer died, and when his family took over

the farm they found that the old bundle of sticks was only in the way, and burned

it. This is a typical situation.

The actual running down of an old airplane usually involves a lot of leg work

in following up third and fourth-hand tips. Some friend of the collector knows someone

else who used to work with a guy who told him that so-and-so's uncle's neighbor

had an old airplane in his barn.

|

1930 Heath Parasol owned by Frank Falejezyc, Lakewood. N.Y. Changes

include 37 hp Continental.

Sopwith Camel owned by Frank Tallman rebuilt from museum piece

soon to be joined by restored German Pfalz D-XDIII.

This 22' home-built first flew in 1930, was rebuilt in '54 as

Hobart Sorrell Special. Cruises at 90 mph with 65 hp Continental.

Fleet "2" owned by Paul Ollembury, Milwaukee, typical of breed

between '29 and '41. This is rare one with unmodified tail.

One of two Hisso Standards used by Paul Mantz in "Spirit of St.

Louis" movie. In WW-I·used Hall-Scott engines.

|

Most frustrating part of this game lies in trying to find out just what kind

of an airplane is involved. Most people are unable to describe an airplane beyond

the point of saying how many wings it has, and to others more informed any old biplane

is a "Jenny." The term "Old Airplane" can easily apply to a 1940 Cub or to a real

antique, and the collector has to answer the sixty-four dollar question of whether

or not the thing is worth the effort of running it down.

The time element is extremely flexible in such cases, too, especially in the

minds of people who are not themselves interested in the subject. Some old farmer

may be quite sure that he saw a plane in a friend's barn over in the next county

just a couple of years ago, but a follow-up often reveals that he actually saw it

ten or twelve years before. All too often, the collector finds that there was a

plane in the place described, but that it had been destroyed a short time before.

As a result, serious collectors have learned not to put off following up a rumor,

no matter how faint, even until next week.

When the antique hunter does locate an old airplane, his problems are only beginning.

First, there is the matter of obtaining it. This can range from the extreme of being

given it in return for hauling it away to writing a check for an amount exceeding

that for which a complete replica could be built, or even patiently waiting for

an obdurate owner to die.

Best example of the first case is that of Jim Mathiesen, a collector of Berkeley,

California, who also owns a Fokker D-VII, a Boeing FB-5 fighter, and a Thomas-Morse

S-4. He happened to know where a 1911 Bleriot had been stored since 1919. He thought

that this would make an interesting exhibit at an airport Open House commemorating

the Fiftieth Anniversary of Flight, so he asked the warehouse owner if he could

borrow the plane. The owner told him that he could - under one condition. Knowing

what such a ship was worth, and expecting to be stuck for a lot of insurance, Jim

asked what the condition was.

"That you get the - - - - -thing out of here and don't bring it back!"

Others are not so fortunate, and there is no way of setting a price on planes

or parts. A set of Jenny wings may have an asking price of five dollars a panel

or five thousand dollars a set, depending somewhat on condition and other variables,

but mainly on who has them and who wants them, and for what.

Once the collector has title to his antique, he is faced with the problem of

restoring it. In practically all cases, the airplane was in pretty bad shape when

it was found, and structural deterioration makes it necessary to replace many basic

components. The fact that most old timers were just pushed off to one corner of

the damp barn without preservative measures of any kind being taken only hastened

the harm done by humidity, rain, livestock, and the accumulation of old junk piled

on it through the years. Because of this, many of the old timers flying today are

antiques in configuration only, practically all of their basic structure having

been replaced with modern materials.

Replacing structural components is not a special problem - new parts can generally

be built from standard materials by conventional methods. Accessories, especially

engines, propellers, and wheels, are another matter. In many cases, the engines

of old airplanes have been removed and used for other purposes, as have the wheels.

Replacement parts for the old engines are hard to obtain, and often have to be made

by hand. Old wheels are often useless because the odd-size old clincher tires are

no longer made. Many owners of antiques are forced to use modern powerplants in

their planes, which many are glad to do in the interest of reliability and safety

at the expense of a slight loss of authenticity.

Cost of restoration is a very variable item, depending mainly on the circumstances

of the builder, who may have a good stock of the material needed instead of having

to buy every item. Then too, he may do his own work or have to hire it done. The

cost of materials alone just for covering an average-size biplane can run to about

$500, and rebuilding an old engine that requires replacement parts to be hand made

can cost much more.

Actual worth of the old airplane when finally restored is not always proportional

to the work involved, nor does age alone add any particular value, as some people

who have spent six or eight hundred dollars rebuilding 1935 Cubs have found out.

Planes of distinct historical or other significance can command good prices,

but other models that qualify merely as old private-owner or commercial types have

no other value, and must seek their own price level in the overall used aircraft

market. The cost of restoration must be considered in relation to the actual worth

that the ship will have when it is finished. This can get to be a sore point between

an owner and a potential buyer. Economics goes out the window when hobbies of this

kind are concerned, and a seller can expect to receive hardly more than the cost

of materials involved.

|

Most "elephant ear" Travel Air biplanes still flying are dusters

or sprayers with modern engines.

Trimotor of Johnson Flying Service typical of ten "Tin Goose"

Fords still paying way via spraying, smoke-jump, transport jobs.

Sammy Mason revived wing-walking act in 1946 with modified Ranger-engined

Jenny. Plane now has 220 hp radial.

Waco 10 (later GXE) typical of many bipes built as late as '29

to take surplus WWI Curtiss OX-5 90 hp engine.

1928 Curtiss Robin modernized with WWI surplus 220 hp Lycoming

engine replacing OX-5. Was owned by Walter Wright.

|

Recent experience indicates that Fleet biplanes in good condition are fairly

well stabilized between $700 and $1,000 even though one could not be overhauled

and recovered at that price today. Aeronca C-3's, on the other hand, have sold licensed

for as little as $200 five years ago, but are now so well thought of as antiques

that the price has climbed to the vicinity of $450 for airworthy models with old

fabric and to $600 or more for rebuilds.

One specialized problem that must be faced by all airplane owners, actual and

potential, is that of storage and working space. Many who have an opportunity to

buy an interesting ship are forced to pass it up because they have no place to keep

it. Many antiques in poor condition have been passed from hand to hand without ever

being worked on merely because of the lack of suitable facilities. On the other

hand, some people with plenty of space available sometimes buy old ships that they

are not particularly interested in merely because they are old enough to be of interest

to someone, and therefore of some value as trading material if nothing else.

As in the antique furniture game, there are fake airplanes as well as fake Queen

Anne chairs, but the owners of the replica aircraft are not held in contempt nor

do they try to pass off their reproductions as the real thing. Configuration is

the important thing, and the copy can usually be expected to have the handling characteristics

of the original, which is not available.

A number of replicas have been built since WW-II, some of which are as accurate

in structure as it is possible to make them while others have been completely redesigned

and modernized. Two Bleriots, authentic except for powerplant, have been built for

recent commemorative flights across the English Channel, and a Sopwith Pup, complete

with rotary engine, is being built from original factory blueprints in Canada. Walter

Bullock, a Northwest Airlines pilot who used to own a 1912 Curtiss before World

War I, built an aerodynamically-similar replica in 1947. He obtained the full satisfaction

of flying that type of airplane while enjoying the peace of mind that went with

a modern engine and steel tube construction.

Jack MacRae, of Hempstead. L. I., has taken a different course entirely, and

completey redesigned the Driggs Dart of 1926 into the "Super Dart." which is regarded

by pilots and CAA alike as a 1953 airplane. Collectors are divided in the matter

of flying old ships - some will put up with any amount of balkiness and unreliability

to keep the old timer "pure" while others stress reliability above all else. For

example, two Pietenpols were seen at the 1955 Fly-In of the Experimental Aircraft

Association; one with the original water-cooled Model A Ford engine and the other

with a modern air-cooled 65 HP Lycoming engine under a modern lightplane cowling.

Entirely aside from the enjoyment that one gets from rebuilding an old airplane,

or flying in one of the few remaining open-cockpit biplanes, two owners of the antiques

derive immense satisfaction from the comment that their old-timers stir up when

they arrive at public airports. The author has obtained very mixed reactions with

his 1931 Razorback model Aeronca C-3. Old pilots who gather around it pat it lovingly,

and tell of how they soloed on that model, or how much time they have in it, but

the younger generation looks it over skeptically and wonders out loud "did you build

it yourself, Mister?"

As a result of the current interest in airplanes of World War I vintage, a listing

of all the presently-known World War I types in the country is presented on pg.

58-59 of this issue, with each individual airplane identified as to owner or location,

and condition. The listing could never be completely accurate, in that many privately-owned

aircraft are constantly changing hands, while others are rumors that have not been

fully confirmed. The distribution of museum-owned planes can be expected to remain

stable.

|