|

The Academy of Model Aeronautics is granted tax-exempt status because part of

its charter is for activity as an educational organization. I think as time goes

on, it gets harder for the AMA for fulfill that part of its mission because presenting

anything even vaguely resembling mathematics or science to kids (or to most adults

for that matter), is the kiss of death for gaining or retaining interest. This article,

"Control-Line Aerodynamics Made Painless," was printed in the December 1967 edition

of American Modeler magazine, when graphs, charts, and equations were not eschewed by modelers.

It is awesome. On rare occasions a similar type article will appear nowadays in

Model Aviation magazine for topics like basic aerodynamics and battery / motor parameters.

Nowadays, it seems, the most rigorous classroom material that the AMA can manage

to slip into schools is a box of gliders and a PowerPoint presentation. That and

a few scholarships each year keep the tax status safe... for now.

This is part three of a series

of technical articles on the aerodynamics of control-line flying. It appeared in

the December 1967 edition of American Modeler. Figures, equations, and graphs do

not begin at #1 because this is a continuation of the series. I do not yet have

the edition for part 2. Here is

Part 1.

Control-Line Aerodynamics Made Painless

In a dead-stick glide, Dave Gierke's excellently

designed NOVI (October issue) displays its smooth, flowing lines.

Altitude angle measurement instrument

Nomograph No. 7

Your airplane is smarter than you are! It knows and obeys every aerodynamics

law.' Which is to say that "old devil" math is really a useful tool. By its careful

application many 'mysterious' factors are made plain.

By Bill Netzeband

Editor's Note: In the Sept./Oct. and Nov./Dec., 1966 issues were presented Parts

I and II of this series. Both the editor and author lacked faith at that time that

enough control-liners would seriously consider the mathematical aspects of design.

Many favorable letters have been received since. Some called us "chicken" for quitting,

This filial article now is published with the observation that it should have been

printed long ago.

Reviewing the introduction to this informa-tive series we may have supplied rather

shaky reasons for going to all these lengths to properly design a "rock on a string."

The fact that most published designs were "brute force" (cut-fit-crash) developed

didn't always detract from their final shape.

It has become apparent that anyone, no matter how misinformed, can run down the

rest of us who "roll our own" designs. So let us elevate the purpose of these reports

thusly: Your finished airplane is smarter than you are! It instinctively knows every

solitary aerodynamic law, and unquestioningly obeys them to the letter. It therefore

behooves us to learn as many of the important laws as possible so that we don't

demand something which that smart lil' ole' airplane cannot do.

We will deal mostly in how and how much with flights into why, where it is important.

Mathematics are an essential part of our process, since without numbers, the principles

are pretty academic and often misleading. As promised, the derivations of equations

generally won't be detailed, except where the final product is clarified. It is

also planned to suggest test methods and/or devices, so that ultimately we may communicate

on the firm base of measured performance, rather than "Gee Whiz, it sure looked

good." So much for reintroduction.

Since you've already peeked at the sketches, we're dealing with the major lateral

and vertical force diagram to evaluate surface lift requirements, maximum level

flight altitudes and a method for measuring the maximum lift for an airplane. Also

a discussion of the propeller as a gyroscope with perhaps the answer to some of

your "mysterious" crashes.

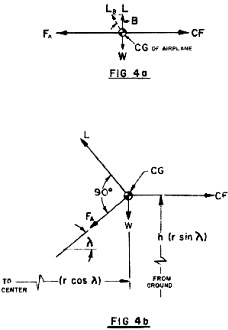

Fig. 4a illustrates the major physical forces generated by restraining a mass

(our CG) in horizontal flight level with the handle. CF is centrifugal force from

Part 1, Nomograph No.3. FA is line tension equal and opposite to CF. W & L are

airplane weight and the surface lift necessary to just equal W. This is the simplest

case, since each vector system is essentially "in line." This is the flight mode

used to determine maximum line tension and trim lift.

It should be noted here that wing lift is assumed to be normal (perpendicular)

to the chord line. If the airplane is banked into the circle (vector LB), the wing

must generate more life to support W, but will allow FA to decrease. For small angles,

up to 10 degrees LB is almost equal to L, and the reduction of FA is W tan B, since

L=W. For a heavy ship (3 lb.) at a 10-degree bank angle, line tension would be reduced

almost 0.5 lb. without requiring additional lift. This effect is directly opposite

if banked outward, and is not proportional to airspeed.

The use of this phenomenon is not desirable for aerobatics or combat, but could

be used for in Navy Carrier (outbank) or a heavy Rat or Speed job (bank in). The

most reliable method to obtain this force is to place the line(s) guide above (bank

in) or below (outbank) the CG of the airplane. Any other method to generate a roll

force (wing warping, ailerons, weight, etc.) will add detrimental side effects (no

pun intended) such as added drag, an angle proportional to airspeed or adverse yawing

effects.

It can be readily shown that a bank angle exists for any line length and air-speed

which would give zero line tension (W tan B = CF). Actually, the amount of weight

is not a factor, since CF can be reduced to its equivalent "g" factor by factoring

out W. Therefore bank angle for zero line tension becomes a product of line length

and airspeed. For 60' lines at 100 mph, angle B would be 85°51' (11 g's) NOT too

practical, but interesting. It is entirely possible that the wing cannot generate

the lift necessary to do a kooky trick like that, anyway.

Points against banking in, are the land-ing and takeoff, where "g" factors of

less than 1/2 are generated. Control can be lost, and/or the airplane could "come

in" on you. Meanwhile, back to important stuff. Fig. 4b represents the real meat

of this sandwich. CF is now calculated for a radius less than the line length (r

cos λ). λ is the angle of elevation, which is some-what easier to visualize than

actual altitude (h), and is more convertible for varying line lengths. (sin λ= h/r).

Under the conditions of 4b, FA is less than FA for horizontal flight (Fig. 4a) since

the lift vector (L) now assumes some horizontal restraining forces. L will be shown

to become tremendous at high angles, and maximum lift capability of an airplane

will limit the maximum elevation angle.

Perhaps we should point out that we are dealing with level flight, not to be

confused with looping and such maneuvers. It is not so difficult to prove that an

airplane can be zoomed into lift factors not available in level sustained flight

due to kinetic energy stored in the system.

Equations 3-1 and 3-2 were derived by conventional vector analysis and are the

basis for the rest of our juggling. To simplify trial analysis we factored out weight

(W), reducing the force system to "g" units, now dependent only on airspeed (V)

elevation angle (A) and line length (r). We then substituted the equation for CF

in terms of "g" units, arriving at equa-tions 3-3 and 3-4. By specifying (V), and

(r), we can calculate line tension and lift at various elevation angles. Calculations

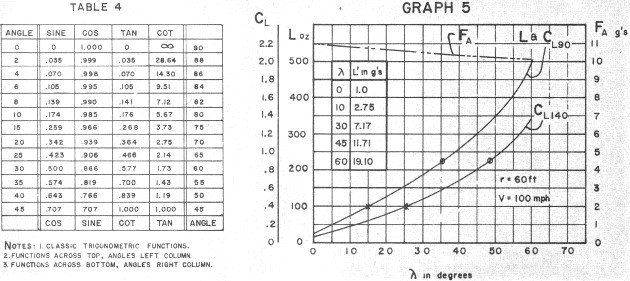

are reduced by use of Nomograph No. 3 (July/Aug. '66) and Trigonometric Functions annotated in Table

4. Simple results are plotted on Graph 5 for an airplane on 60' lines traveling

at a constant 100 mph. To get actual forces, simply multiply "g" factors by W. Sample

numbers would apply to a slow Rat at 26 ounces. L in "g"s are listed.

Come now the engineering compromises. We cannot get lift without drag. Increased

lift causes increased drag. so without being able to increase thrust, the higher

we fly. the slower we go. O.K.? Since high flying is one large bone of contention

in contest judging, we should know where a "point of diminishing returns" is reached.

Or should I fly at the maximum allowed height or not? (We do not advocate cheating!)

Space does not allow complete evaluation of induced drag at this sitting. so complete

analysis of actual speed reduc-tion versus "apparent speed increase" will merely

be dangled before you. right now. ("Apparent speed" is equal to V actual/cos λ).

Of immediate interest is maximum lift. since we now have most of the machinery

to measure it. To evaluate a given airplane a graph or series of point calculations

leading to L versus λ are necessary. For most CL airplanes a Lift Coefficient

(CL) of 0.9 is about the limit before going into hard stall conditions.

Nomograph 7 will calculate L, D, or CL and CD depending on

the order of procedure. (Eq. 3-5 and 3-6) If. as we have right now, values for L,

we can calculate CL. The example shown on the face of the Nomograph can

be solved for CL by proceeding as follows: 1) Pick up wing area (S) and

lift required (L) with straight edge and hold crossing point 1; 2) Holding 1, swing

to V on left hand scale, reading answer CL on RH scale.

Lift coefficient (CL) is a figure of merit defining the lift per unit

area of a wing for specific conditions of Reynolds Number and angle of attack. It

is necessary to introduce it, unadorned, so that we have common ground to complete

this discus-sion. As we said, except for a high efficiency stunt wing with high

lift devices, most CL wings will stall at CL = 0.9. At this

point drag is extremely high, and lift will decrease if you force the wing to higher

angles of attack. An end point for high lift without excessive decrease in airspeed

due to induced drag is closer to 0.3 or 0.4.

Having plotted or tabled L and corresponding CL versus λ, pick out

the CL of interest, and note the elevation angle. This is the maximum

angle at which you can fly level (if CL were 0.9) or maybe the highest

to fly for best "apparent speed."

During all of this, a detailed study of FA indicates a small decrease in line

tension as λ increases. From Eq. 3-1, at 90 degrees line tension disappears except

for airplane weight coming down. From Eq. 3-3 it appears to be different, that line

tension in "g" units is equal to horizontal g's reduced by sin λ (which varies from

0 to 1.0). The apparent mathematical anomaly is caused by the fact that under practical

circumstances CF for a zero radius is infinite, such that correct procedures require

definition of max-min values by calculus. We cannot practically reach these limits,

so they are hereby ignored.

If we apply wing areas of 90 sq. in. and 140 sq. in. to our sample plot and a

fixed weight of 26 ounces, we have a country fair argument for the larger area Rat

Racers. F'rinstance, applying CL of 0.4 for best speed at altitude, the 90 comes

in at 15 degrees, the 140 at 26. Maximum elevation for the 90 is conservatively

35 degrees as opposed to 49 degrees for the big one. Granted you can zoom maybe

ten degrees higher to pass, but you won't stay up there long! Note also, that line

tension is reduced by only 0.9 "g" even at 60 degrees, although the speed reduction

we know exists will cause an actual reduction. since CF will decrease. Finally,

20' (max. racing altitude, except passing) represents an λ, of 19.5 degrees. not

too encouraging for the 90. if the 140's decide to run at 20 ft!

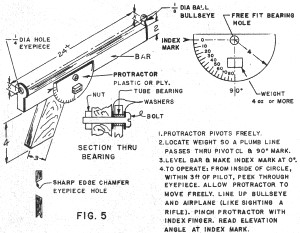

If we had a way to measure V and (λ) while flying our airplane, without wind,

at its highest altitude, we could calculate its maximum lift coefficient. Luckily,

both can be measured with reasonable accuracy, if you want to take a little time

to build a crude theodolite from Fig. 5. Using the gadget like a pistol, sighting

through the eyepiece until the bulls eye covers the airplane, while several laps

are clocked with a stop watch, you have both angle and velocity nailed down. (V)

can be calcu-lated from Eq 3-7.

Knowing the angle (λ) and velocity, we can plug these numbers, along with (r),

into equation 3-4 and come up with (L') in g's. By multiplying (L') by (W), we have

(L max) from which CL max can be calculated from Nomograph 7 (Eq. 3-5

or 3-6). This would settle many questions, like in stunt as to just what CL

is a prac-tical maximum. The reduction in airspeed from level flight (minimum drag)

will give a measure of drag increase. It is needless to tell you that this information

is useless, unless you dig in and apply it, isn't it?

Particularly significant in stunt and combat is maximum lift, since this determines

the minimum looping radius. It has become apparent that indiscriminant use of full-size

airfoil data has led to some extremely optimistic turn radii. We seldom achieve

the efficiency of a large wing at high speed. Therefore, to derive useful data we

are using experimental measurements such as this one to write our own book.

The next phenomenon has been pub-lished before, without specifically pointing

out one dangerous area. The propeller acts as a gyroscope since it is a rotating

mass and numerical analysis proves that under adverse conditions it can generate

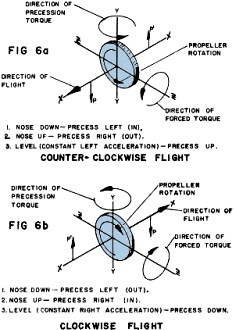

enough precession torque to cause trouble. Referring to Fig. 6a we see the conventional

forces associated with a gyro. The physics of the system are too complex to put

down here; only the results will be presented. Essentially what occurs for conventional

prop rotation (CCW when viewed from front), when the rotation axis X-X (prop shaft)

is tilted, a reaction torque appears in one of the axes perpendicular to the X-X

axis.

In the case shown in Fig. 6a, we are flying in the conventional direction (CCW)

and move the nose down (coupling forces P-P'). This rotation is about the Z-Z axis

and the precession torque appears about the vertical axis Y-Y in the direction shown.

All of the forces involved here are couples (two equal and opposite forces in the

same plane, but not along the same line). A couple is handled as a torque (a force

on an arm causing rotation) and can be balanced only with an equal and opposite

couple or torque. These facts cause the precession force to be independent of its

distance from the CG, so long or short nose lengths do not affect it. Therefore,

the illustrated torque appears at the CG turning the nose into the circle.

As noted, nose up turns produce nose out torque, while the steady left hand acceleration

of level flight produces a small nose up torque. These are all real, sport fans.

The amount of precession torque depends directly on the mass (weight) of the propeller,

its diameter (specifically the CG location of each blade), the engine rpm and the

angular acceleration (rate of airplane turning) which is in turn dependent on airspeed

and turn radius. The larger any of these, except turn radius, the larger the precession

torque.

There are several danger points in the precision aerobatic pattern, where high

rates of nose-down pitch are required, the square eight and the middle two corners

of the hourglass. Noting. the reversal of conditions in inverted flight (Fig. 6b)

one can include the second and third reverse wingover corners and bottoms of outside

square loops. The effect can vary from momentary loss of control to complete loss

of airplane.

In the early days with the climb and dive maneuvers we had troubles, too. To

deliberately look for this force John Barr and I took his late "Lil Satan" with

ST 15 diesel power, increased the stabilator area for sharper turns and performed

hairy climbs with sharp pullouts. Finally with a 9-3 prop, relatively slow airspeed

(low line tension) and high rpm, we started getting it every time. The nose would

swing in violently, the ship would completely slack off and float to the other side.

During the initial test series we were ready and could regain control before it

crashed, but during a night session she pulled the bit so quickly and accidentally

that the end arrived. The stunt ship with its marginal centrifugal force and a combat

rig with a slight warp and high rpm mill are prime victims for this force. Since

plastic props weigh about 50 percent more than wood props they will generate 50

percent more precession force.

The effect of the small nose-up or down-precession in level flight explains the

apparent stability increase while flying inverted since the effect is destabilizing

in CCW flight and stabilizing in CW. This probably explains why the majority of

the "developed" stunt rigs end up with a raised thrust line, to partially compensate

for the precession effect on trim.

|