|

Author Don Berliner claims in

this April 19711 issue of American Aircraft modeler magazine that, "[The Owl Racer]

is the easiest racer to model for RC pylon." Curiously, given that claim, no plans

were published for it, but there are 3-views. Designer George Owl (I kid you not)

applied knowledge gained from the School of Hard Knocks in the field of airplane

racing on top of his ample experience with "brains-and-slide-rule" design to create

this winning craft. Did you catch that? "Brains-and-slide-rule." Is that Flo from

Progressive Insurance starting the airplane?

Owl Racer

Don Berliner

Unique because of new ideas, the Pogo proved it has winning potential in its

first two races. Smooth lines make it suitable for any model project.

The owl is a pussycat. And a tiger. And a 'possum.

A pussycat, because Bud Pedigo, first pilot to race this new Formula One, says

he'd turn a student loose in it.

A tiger, because it blasted around the three-mile oval at St. Louis at 209 mph

its first time out.

A 'possum, because it's now named Pogo, who is one of the better-known 'possums

of the Okeefenokee Swamp.

Only engine performance information really matters in any racer.

Pogo is not flown cross-country to the meets, so minimum instruments are used.

Designer theorized that less wetted area and fewer cowl intersections

offer less drag than the typical tight-fitting cheek cowl. This is the easiest racer

to model for RC pylon.

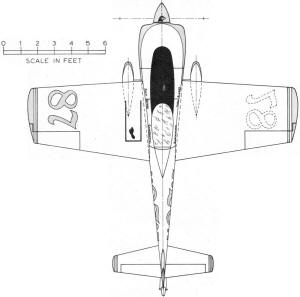

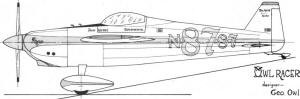

Pogo's color scheme is metallic olive green striping and numerals

on solid white, with a black antiglare panel in front of the cockpit. The tail wheel

is tiny.

And the Owl Racer because it was designed by George Owl, who has been involved in

the brains-and-slide-rule part of airplanes ranging all the way from Midget Monocoupe

to X-15.

Engineers, as a general rule, don't make very good raceplane designers, for they

tend to build airplanes that are too big and too heavy. But an engineer with racing

experience is another matter, and that is the exclusive category into which George

Owl fits quite snugly.

He got into the raceplane racket in 1947, when the Goodyear Racers flashed onto

the scene and it seemed as though just about everybody was starting to build one

- or at least was talking about building one. George was no exception, but his airplane

was. It was the one and only high-wing ever proposed for the 190 cu. in. class.

He built it for Woody Edmundson, then a rather successful pilot of racing-P-51's

and aerobatic Monocoupes, and now a very successful charter flying operator.

The racer was called the Midget Monocoupe, and looked like one, with a Monocoupe's

classic tapered wing atop a very small fuselage. It was ready in 1948, but Woody

found it entirely too hot to handle, so it never got to Cleveland, although Woody

and his other airplanes did. The Midget Monocoupe drifted around for years, finally

becoming the property of an EAA type in Miami, name of Henry Watts, who improved

its flying characteristics and entered it in the 1969 Florida National Air Races.

Everyone was impressed by its sporty looks, but the officials frowned on its wobbly

flight path and ordered it to stay on the ground, where it will probably remain,

at least when other planes are racing.

Owl had long since moved on to bigger and better things, changing jobs from Aeronca

to McDonnell and then developing possibly the most radical racer in history-the

P.A.R. Special. This slick little craft boasted an engine buried behind the pilot

and driving, by means of a six-foot extension shaft, a Fairey pusher prop "mounted

aft of the Y-tail. As if that weren't enough, it also had a variable-incidence wing.

But no amount of fine engineering, workmanship and piloting could overcome the drawbacks

of the long shaft, which distorted during high-g turns, and so it was retired after

achieving a best performance of 181 mph at Chattanooga in 1952.

His radical ideas having brought no success, George Owl vanished from the racing

scene and busied himself at North American Aviation, designing such run-of-the-mill

flying machines as the B-70 and X15, neither of which made so much as a ripple in

the air racing pond, although they reportedly were fairly fast.

Shortly after air racing returned in 1964, so did George Owl, this time well

armed with ideas, vastly more experience, and an expert builder named John Alford.

Together, they developed the Owl Racer. Hardly anyone knew of its existence until,

as if by magic, it appeared on the ramp in front of the race hanger at St. Louis

in August, 1969.

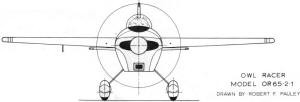

The machine was beautiful, no doubt about it. Its lines were smooth and artistic.

Its construction and finish were the equal of any racer in the country. But it looked

a bit on the large size, especially in the front end. Polite questions about the

reasons for the bulky cowl brought a painstaking explanation from its designer.

And while it was obvious that a lot of racing veterans were far from convinced by

the explanation, none of them was equipped to argue aerodynamics with a guy like

George Owl.

The other half of the team was John Alford, an air tanker pilot flying Grumman

F7F Tigercats. A qualified mechanic as well as pilot, John had converted Stearman

trainers to dusters, restored Beech Staggerwings, and flown B-17s in forest fire

operations. In addition to an outstanding job of construction, John will soon make

a further contribution to the story of #87. His wife, Joan, will be its pilot for

1971, and thus the first woman to compete in Formula One.

A lot of brand new racers are exceedingly fast on the drawing board, in the workshop

and at the home field. And a lot of pretty bubbles are burst in that first spin

around a race course, when the unbiased stopwatch converts dreams into reality.

But this time there was nothing for the Owl crew to apologize for, as pilot Bud

Pedigo clocked 208.90 mph, good for sixth place in an amazingly fast field of 13

racers. Four years of careful planning and hard work began to payoff.

The Owl Racer didn't become the Cinderella plane of the year by beating Rivets.

In fact, it didn't even make the Finals in its first try, being plagued by poor

takeoff acceleration. Still, it topped 200 mph in the Consolation Race and put everyone

on notice that more would be heard. A few weeks later, at Reno, Pedigo earned over

$1000 by flying #87 into fifth place in the Formula One Championship Race at almost

204 mph.

Such performance for a completely new design, while not unheard of, is certainly

rare. How did Owl and Alford do it? By careful detail work, by precise alignment

of every important piece, and by knowing which tried-and-true techniques to use

and which to ignore when their own calculations pointed down an untried path.

The main deviation from conventional design in the Owl Racer is its cowl - large,

but simple. The Owl cowl, according to George, has less surface area, no sharp intersections,

more interior space and a better shape for withstanding pressure. Moreover, it has

a blunt front where the cooling intakes are located, to accommodate a steep angle

of airflow without stalling, thus producing maximum cowl thrust, similar to wing

lift.

The original exhaust and cooling systems were worth note, with both exiting on

the bottom of the airplane, just ahead of the firewall. The stacks were located

at either side of a cowl flap in a very clean arrangement. After the 1969 season,

the exhaust system was lightened and simplified by switching to individual stacks

cut off flush with, ports on either side of the cowl. Other changes, mainly aimed

at reducing weight, are to include elimination of the oil radiator, replacement

of the thick galvanized firewall with aluminum and asbestos, and switching from

copper pitot and static lines to plastic or aluminum.

Construction is straightforward. The wing has a one-piece laminated spruce main

spar, half-inch thick spruce ribs and plywood covering. Aileron control is via a

one-inch torque tube which can be disconnected for easy wing removal by pulling

a single bolt in the cockpit without affecting aileron rigging. The fuselage is

welded chrome-moly steel tubing with metal covering to the front of the cockpit

and fabric aft. The tail has a spruce frame covered with plywood. The canopy is

a single piece of molded Plexiglas with a composite wood/ foam/fiberglass frame

and rear fairing.

Power is supplied by the typical stock Continental 0-200, properly balanced and

with a racing prop which enables it to turn about 3750 rpm and develop about 125

hp.

One season of racing, even when it is as successful as the Owl's in 1969, still

doesn't prove a design. At best, it can only indicate potential. The Owl Racer unquestionably

has speed and good flying characteristics, which is about all that should be asked

of a racer. Its future is bright but completely uncharted. Plans, available from

John Alford (291 Beech Ave., Santa Rosa, Calif.) for $125 a set, consist of 56 individual

drawings including all structure, primary controls, fuel tank and canopy, as well

as full-size ribs and fairing contours. Their acceptance by builders could make

the Owl Racer one of the truly significant racer designs. In the meantime, #87 will

be busy trying to win races.

Color Scheme

Basic airplane is white with metallic olive green striping and numbers.

Black pilot name, airplane name and emblem on vertical stabilizer, wing-walk

and footprint on upper surface of left wing, and cowling anti-glare panel.

Specifications

| Wing

Span - 16' 0"

Area - 66 sq. ft.

Airfoil - 63 A 210

Dihedral - 1 degree

Aspect ratio - 3.88:1

Incidence - 0 degrees

Twist - 0 degrees

|

Stabilizer/elevator

Span - 5' 11"

Area - 8.5 sq. ft.

Aspect ratio - 4.12:1

|

| Stabilizer/rudder

Area (projected to fuselage reference line) - 5.10 sq. ft.

|

Owl Racer Top View

<click

for larger version>

|

Owl Racer Side View

<click

for larger version>

|

Owl Racer Front View

<click

for larger version>

|

Posted December 11, 2023

(updated from original

post on 4/28/2012)

|