|

Control line flying seems to be making somewhat of a comeback lately

- some ARF C/L models are appearing in the magazines. It is still

not as popular, but gaining ground. A fly-in here in Erie, PA, recently

included a local C/L club that I did not even know existed - the

Bean Hill Flyers. Unfortunately, the ranks of today's top fliers

are not populated like with the R/C world. The rapid reflexes and

incredible hand-eye coordination of the teenagers who dominate extreme

R/C flying would clean up in the control line realm. I'm guessing

a cloverleaf would be a piece of cake to a 16-year-old who could

invent maneuvers that would make Bob Hunt's or Windy Urtnowski 's

hair stand on end.

Hawker Typhoon

Slick semi-scale Nats winner was designed, described and pencil-drawn

by 14-year-old Junior Stunt Champion.

By Dennis Adamisin

"It certainly separates the men from the boys!" Such was one

pilot's evaluation of the Typhoon. When it proved to be an ineffective

high-altitude fighter, the Typhoon seemed doomed. However, it later

saw action as a ground-attack support fighter.

This model represents a phase of stunt design which has featured

jets, Goodyears and originals. The Typhoon is the first semi-scale

airplane in this group, but it has many of the features of earlier

models. It is definitely the best ship I have had, and I am building

another one for a spare.

The paint scheme is semi-scale, different, flashy, and easy to

do. The camouflage is green and brown; the green sprayed first and

the brown air-brushed on later. The bottom is yellow with black

diagonal stripes. The first two letters of the identification are

red, the last letter is yellow and the letters on the rudder and

the nose are white. The band on the back of the body is light blue.

The white letters on the cowl read, "If this engine catches fire

on starting, don't just wave your arms at the pilot, try putting

the bloody thing out as well." The letters on the side of the body

just ahead of the elevator read, "If fate decrees that I should

fail, then fate will not have watched my tail." These two tidbits

were on the real Typhoon. My best flights were made with this airplane

when it was flown slow and smooth. Not to say that it won't fly

any other way - but who knocks success? The Nats' victory was mine

after only one official flight! The advantages of flying smooth,

instead of by the book, are several. It's easier to fudge in at

the right altitudes, especially at the bottoms of everything. Most

important, bobbies or "bombing out" on the bottoms of the square

maneuvers can be avoided. Less practice is needed and one can stay

in practice longer. A smooth pattern impresses the judges because,

without all the bobbles and imperfections of a square pattern, a

smooth pattern just naturally looks better.

A few general comments on Stunt should be made. First, many fliers

are unhappy with the AMA method of scoring. Some would like to change

the point values or adopt F AI scoring; others have their own systems.

All these proposals have the same fault: they depend on humans to

operate them. As long as this is true, the end result will be the

same. Second, many people disagree with appearance points. Some

want to halve their values; others want to double them. I feel increasing

these values emphasizes them too much. If values are decreased,

too many people will be content with a kit, because realism and

originality wouldn't be enough to work for. If anything, I'd like

to see a fifth category for general appearance. The total point

value would remain at 40, with each category being worth three to

eight points. Third, I don't favor iron-on finishes, but I do feel

that if a builder does a nice job of putting one on, he deserves

credit.

Psychedelic paint job on the plane's underside

is for real. Colors are copied from a Profile Publication showing

a target tug. It really catches judges' eyes - a help in winning.

A problem which has plagued stunt models for years is that nasty

little word, weight! The general consensus is to avoid using hard

balsa and hope for the best. We, and there are five of us here who

build and fly stunt, have discovered a new method which allows us

to build airplanes with fully-sheeted wings as light or lighter

than the conventional "open-bay" configuration. Un-fortunately,

this technique was not used in the Typhoon because I had not realized

its potential. My model is 48 oz., four or five oz. heavier than

it could 'have been.

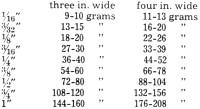

I refer to the idea of using a gram scale in the selection of

the wood. A sheet of 1/16 x 3 x 36" should weigh less than ten grams.

The difference between 10 and 14 grams may not sound like much,

but if four grams are saved per sheet on the ten pieces of wood

needed to sheet the wing, 40 grams or roughly one and a half oz.

are eliminated on the sheeting alone! Apply this to the ribs, spars,

tips, and flaps, and two and a half to three oz. are saved just

in the wing. The fact that stunt planes are already overbuilt allows

this to be used to a weight-saving advantage. Hard, heavy wood need

not be used in building the fuselage.

Light

wood in the tail section cuts down on ballast needed in the nose.

The three to four, or even five. oz. are the difference between

an average airplane and an excellent competition stunt ship! Listed

is a table of weights which should help in the selection of light

balsa. This chart gives the approximate weight for 36-in. lengths.

Lighter wood would be great; but avoid using wood heavier than this.

With light wood, you are halfway home. Sensible techniques in gluing

add to weight savings. Use only enough glue to hold the joint, not

the world. The joint is only as strong as the wood. In areas which

have to endure severe strains, use epoxy. Light

wood in the tail section cuts down on ballast needed in the nose.

The three to four, or even five. oz. are the difference between

an average airplane and an excellent competition stunt ship! Listed

is a table of weights which should help in the selection of light

balsa. This chart gives the approximate weight for 36-in. lengths.

Lighter wood would be great; but avoid using wood heavier than this.

With light wood, you are halfway home. Sensible techniques in gluing

add to weight savings. Use only enough glue to hold the joint, not

the world. The joint is only as strong as the wood. In areas which

have to endure severe strains, use epoxy.

Construction

Since it is the heart of the airplane, begin with the wing. Its

construction is different but simple. The 1/16 x 1/4" pieces help

line up the ribs and are cut with a Woodruff key-cutter in a drill

press set at the proper height. This allows the wing to be built

in a jig, which helps prevent building warps into it. Begin by cutting

notches about 1/16" deep into the leading and trailing edges. The

ribs are made by cutting the center and the end rib templates out

of 1/16" plywood. Sandwich 13 pieces of 1/16" medium soft balsa

between them for each wing. Carve and sand them and then repeat

the procedure for the other wing.

Cut the notches for the leading and trailing edges and for the

spar; hollow as shown. Use the front of the rib templates for making

the half-ribs. These will be cut to length later. Cut the spar out

of medium to soft 1/16" sheet, making sure that the outboard spar

is one inch shorter. The ribs are then slipped onto the spar. On

a large flat board, the leading and trailing edges then are blocked

up high enough to clear the ribs.

Cut the bell crank floor out of 1/8" five-ply plywood. Slide

the ribs and spar into the jig and slide the bellcrank floor into

the spars. Line up the ribs and glue them into place. Cut an opening

large enough for the bellcrank in the spar. Epoxy Vg" plywood doublers

onto the bell crank floor. Drill the hole and install the bellcrank

with a 3/32" pushrod. Install a second platform to help carry the

load. Sand down the leading and trailing edges until they match

the airfoil.

Cut the landing gear platform out of 1/8" plywood. Bend the landing

gear out of 1/8" wire and tie it to the platforms with J-bolts.

Install the platforms and reinforce the ribs and spar with 1/8"

balsa. Cut and install the half ribs. Sand the entire structure.

Now to sheet the wing. Cut all the edges using a straightedge

to insure a close fit. Pin the trailing edge down on the board with

the landing gear hanging over the edge. The first sheet is four

in. wide and can be full length on the trailing edge. The next sheet

is six in. wide and must be joined in the middle. This still leaves

part of the leading edge uncovered. Cover it and repeat the procedure

on the bottom. Allow to dry thoroughly.

Cut out the flaps. Cut, notch, and drill hole for Top Flite radio

control horn. Carve flaps and assemble them. Cut wing tip cores

out of 3/8" soft balsa. Cut the top and bottom blocks out of 3/4"

soft and spot glue them together. Locate and drill leadout positions.

Sand the flaps flat and spot glue them to the wing. Carve and sand

to shape, then remove. Hollow tips, add leadout tubes, three-quarters

to one oz. of wing tip weight. Assemble and glue to the wing. Hinge

the flaps; add and carve the stationary flap. Glue the 3/8 x 3/8"

triangular cap to the leading edge and sand the entire wing.

The stab and elevator are cut out of 3/8" soft balsa. Carve to

shape, leaving the area in the center of the elevator one-in. wide,

flat and square. Install the control horn and hinges.

Cut the outline of the fuselage from 3/16" soft balsa sheet.

Using the wing, make a template of the airfoil. Mark the center

of the leading edge and trailing edge on it for cutting out the

hole for the wing.

Cut out the motor mounts and taper and drill them as shown. Epoxy

these to the body sides. Cut out the two plywood bulk-heads. I used

a World Engines' four-oz. stunt tank with a stock venting. It ran

well, but too long for the seven-minute FAI Pattern. However, for

the regular AMA Pattern, it is excellent. Epoxy the tank and the

bulkheads to the inside (left) body side. When this has set, make

a jig for holding the fuselage together and in line during assembly.

Epoxy the front-end assembly to the right (outside) body side

and slide the whole thing into the jig. Pull the back of the body

together and glue it around the 1/8" spacer. Add the bulkheads,

which are cut from 1/8" balsa. Cut out the small part of the body

by the trailing edge. Block up the wing in the jig so that when

it is glued in, it won't be cocked or leaning. With this done, the

wing can be glued in. If the center of the stab was left flat, it

can be glued into the fuselage at the same time, lining it up perfectly.

Then make the pushrod. I used 3/32" wire with a Kwik-Link on

the end by the stab. Install the fairleads, making sure that they

don't foul on the pushrod, which would make it bind. With the fairleads

installed, the controls should be almost free enough to work on

one leadout. If they are tight, work on the controls until they

are free. Twenty flights can't be wasted waiting for the controls

to work free.

Locate the engine, drilling for a two degree offset. Sand the

front end at a two-degree angle. Cut out the nose ring from 1/8"

plywood, locate and epoxy it to the front block. When the epoxy

hardens, cut out the top block and spot glue it to the body. Cut

out the back half of the bottom block and spot glue it to the body.

Cut out the front half of the bottom block, sand the airfoil out

of it and spot glue it to the body. When all of this is dry, carve

and sand to shape. Pop them off and hollow. The top block, when

hollowed, should not exceed one oz.; the same applies for both of

the bottom blocks together.

Bend the tail-wheel .075" wire and bind it to the 1/8" plywood

platform with 1/2A flying line. Epoxy the entire structure. Cut

out the doublers for the body sides and epoxy the doublers and the

platform to the body. When hard, cut the clearance for the wire

into the bottom block. With this done, all of the blocks can be

glued on.

Now to begin construction of the cowl. Cut out the 3/8" sides,

1/4" spacer (on the face of the angled part), the 3/4" block, and

the front blocks. Line up all the blocks and epoxy them together.

When the epoxy is hard, spot glue the cowl to the rest of the airplane.

While this is drying, cut out the rudder and fin and glue these

pieces together. Carving the cowl isn't as hard as it might look.

Just use the cross-sections on page 37, September 1969 AAM. With

this done, pop it off and hollow it out. Make the hold-down. Cut

out the exhaust hole, the air outlet and air intake, and coat its

interior with epoxy, making sure to work the epoxy into the wood

to fuel-proof it. Carve the fin-rudder assembly and add it in place.

I used an eight-in. Midwest canopy because of the ridges that

show where the back half of the bubble is separated from the windscreen.

When painted, they add to the overall realism. Notch the canopy

into the top block and add the cockpit detail. If a pilot is added,

his size must be comparative to the plane's scale. Epoxy the canopy

into the notch. Epoxy is the only adhesive that won't dissolve the

canopy but will still hold it down. Cut out, carve, and glue on

the flap fairings. Perfectionists may add elevator fairings.

Put on the fillets. I use Epoxolite putty because of its toughness

and its resistance to cracking. It dries so hard that the fillets

must be as close as possible to their final shape while they are

still wet. To accomplish this, tape the outline of the fillet onto

the airplane. Then smear the goop into the outline, shape with finger

and water. Allow to dry for 20-30 minutes. At that time, peel off

the tape and feather the edges, once again with finger and water.

When satisfied with the shape, allow the fillets to harden overnight.

Sand with coarse paper.

Covering the structure with light tissue is essential for obtaining

a light, high-quality finish. Grain, pinholes, small knicks and

other small surface imperfections are hidden. I use "Jap tissue"

because it is light, fills quickly, and therefore suits the purpose

nicely. My covering procedure is different, so it is given in detail.

After filling in the big dents and/or gouges, apply three unthinned

coats of clear, sanding between each one. Now for my method. Place

the dry tissue on the surface to be covered. Saturate the tissue

with thinner. This softens the clear and causes the tissue to be

virtually absorbed into the surface. Rubbing the tissue into the

clear helps fill the tissue with clear from the bottom. When dry,

fill with clear and talcum-clear. Use your favorite finishing method

or, if in doubt, consult the articles on finishing by Dave Gierke

or Don Bambrick.

The only other detail needing explanation is the wire used as

an extension of the plug post. On the plans, it is shown just below

the cowl. It is hooked onto the plug and trailed through the air

outlet. I used this device to eliminate a large, unsightly hole

in the bottom of the cowl. It worked well and I had no problems

with starting the beast.

Wait for a relatively calm day to test fly. Except for a little

nose weight and an extra quarter-oz. tip weight (I originally had

a half ounce) I had no difficulty in trimming the Typhoon.

<click for larger version>

Notice:

The AMA Plans Service offers a

full-size version of many of the plans show here at a very reasonable cost. They

will scale the plans any size for you. It is always best to buy printed plans because

my scanner versions often have distortions that can cause parts to fit poorly. Purchasing

plans also help to support the operation of the

Academy of Model Aeronautics - the #1

advocate for model aviation throughout the world. If the AMA no longer has this

plan on file, I will be glad to send you my higher resolution version.

Try my Scale Calculator for

Model Airplane Plans.

Posted October 2, 2010

|