|

An

extensive article introducing non-modelers to aircraft modeling

appeared in the Annual Edition of the 1962 American Modeler magazine.

15 pages were devoted to describing just about every aspect of model

building and flying - free flight gas and rubber; control line stunt,

combat, scale, and speed; helicopters and ornithopters; indoor gliders,

stick and tissue, and microfilm; even some early radio control.

In order to keep page length here reasonable (because of all

the images), the article is broken into a few pages. Pages:

|

10 & 11 |

12|

13 |

14 |

15 |16

|

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |23

|

24 | For Non-Modelers: All About Air Modeling

20 Easy Ways to Go Crazy! <previous> <next>

What do you do when the sun goes down at the National meet.

Just build yourself a towline glider like 10-year-old Charles

Lawrence, above.

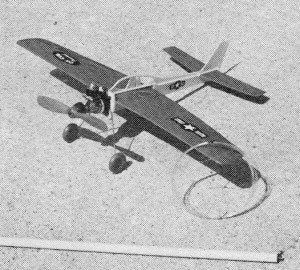

Man chasing model? No, member of official U. S. Air Force team

in annual American championships hand-launches combat class

control line fighting plane. Note paper streamer.

All-plastic ready-to-fly beginners gal model, an OK Cadet. Comes

with motor, line, flying pole.

PLASTIC SCALE - Assembling and decorating plastic

scale model kits is usually the first activity of the young newcomer

to the modeling hobby. He has hundreds of models to choose from.

Indeed, the whole history of aviation is spanned in an array of

plastic models from the Wright Flyer to the latest jet transport.

Minimum handicraft skills are required to put together plastics

and most modelers soon build up quite a collection (sometimes to

the despair of the lady of the house, who says dusting them can

be a problem). Practically all plastic kits provide decals for insignia

and other markings. However, the modeler with an artistic bent can

make a real hobby out of painting-in these details with enamels

especially designed for use on plastics. The wealth of minute

detail on today's plastic scale models turns old-timers green with

envy. Solid scale exhibition (non-flying) models have always been

a part of the modeling picture. Its beginnings were crude compared

to today's plastics. A kit used to consist of a rather crudely drawn

3-view, with perhaps a few cross-sections. Wood blocks of pine (early)

or balsa (later) were cut to approximate size and thickness. The

modeler had to cut or saw these blocks to profile and plan outlines

then carve and sand to required cross-section. Eventually manufacturers

produced kits with the wood machine cut to near-finished outlines

and cross-sections. This was a major advance and took the labor

out of the whittling process. But if a modeler wished to crowd on

the detail he had to improvise with pins, wire and thread and a

smooth paint job was not easily achieved. The modern plastic

model takes all these trials and tribulations out of this type of

modeling. The very smallest detail such as rivet heads are cast

right in the plastic, finish is smooth and results that formerly

took hours to achieve now are accomplished in minutes. The

plastic scales are a most important first step into model aviation.

For the beginner' they serve as a valuable educational function

by familiarizing him with the shapes and names of the parts of an

airplane. Their decorative value is unsurpassed.

READY-TO-FLY - The model types in this category

range from the simplest "chuck gliders" and windup rubber powered

R.O.G.s (Rise-off-ground) to the electric motor powered and the

small gas engine powered plastic flyers. Any and all of them enable

the new modeler to progress quickly from the static to the flying

stage. The simplest balsa slip-together chuck glider such

as the A-J "74 Fighter" can provide hours of flying fun and at the

same time demonstrate the rudiments of flying trim and balance.

Though simple looking, these gliders have sheet balsa wings curved

to airfoil shape and dihedral giving a high degree of stability

and performance. The thick sheet balsa profile fuselage is slotted

for the wing and tails providing a knock-apart feature to minimize

rough landing damage. By sliding wing forward or back in the fuselage

slot the glider can be made to climb and stall, dive or glide smoothly.

Tails and wingtips can be bent slightly to give rudder and aileron

action changing steepness of bank and turn. Larger sheet

balsa gliders can also be launched with a rubber band sling-shot

and some have folding wings permitting launch to high altitude with

prolonged glide resulting. Progressing from "arm power"

to the simplest mechanical power the modeler finds the rubber-powered

R.O.G. There are numerous versions manufactured. All are similar

to the slip-together chuck glider having formed sheet balsa wing

and tails, a sticklike fuselage, a plastic propeller, rubber strand

motor, wire landing gear and wheels. Some "wind-up" models have

a free-wheeling arrangement on the propeller so that when rubber

power is used up the propeller will turn by itself creating less

drag thus giving a better glide. The simple R.O.G. provides

excellent training in the handling of power in a model. The modeler

becomes aware of the importance of taking off into the wind. He

becomes aware of the forces exerted by the rotating propeller on

the model's flight. The simple turn and glide adjustments to tail

and wing require more careful handling when coupled with propeller

power. In addition to the stick fuselage R.O.G.'s other

ready-to-fly models have more realistic profile or rotted-sheet

fuselages. There are also rubber-powered helicopters which

will climb straight up and then descend slowly without damage. The

catapult or slingshot folding wing glider idea has also been applied

to the helicopter. This model is provided with folding rotor blades

that open at top of launch and revolve letting the whirly bird float

gently down.

All

of the chuck gliders, R.O.G.'s and copters have one feature in common.

They are flown in free flight, that is, once launched or released

they are "on their own." The course of the flight is determined

by the adjustment made to the model before launching. In this the

modeler has been greatly aided by the manufacturers. Most trim adjustments

are built-in at the factory, giving the modeler a minimum of fussing

and a maximum of flying fun. A recent novel innovation in

tethered or controlled flight type of model is the electric motor

powered Stanzel "Electronic jet." This prop-driven model combines

plastic and balsa construction and comes completely assembled, ready

to fly. A battery powered electric motor is contained in a hand

held power unit. The model propeller is turned by a length of flexible

cable extending from the power unit to the model. The motor (and

propeller) can be turned on and off by a switch. The model can be

flown in a 15' diameter circle with the flyer standing in the center.

With power turned on model will take-off and can be landed by turning

power off. Circular flight can be aided by leading the model with

the cable and by "beeping" the switch to vary amount of power. Twisting

the plastic tubing housing the cable gives moderate up and down

control of the model. This simply controlled and powered

model is a fine example of a well-engineered product that provides

the young modeler with an excellent stepping-stone to more advanced

controlled model flying. The lure of gas engine power is

inescapable for the beginner. Fortunately he can achieve early flying

success with the many engine-powered plastic control line models

available. He will find semi-scale and scale versions of many big

aircraft types from antique biplanes to guided missiles. There are

also simplified tethered trainer types that require a minimum of

flying skill yet still provide good training in engine starting

and operation. <previous> <next>

Posted December 25, 2010

|