|

An

extensive article introducing non-modelers to aircraft modeling appeared

in the Annual Edition of the 1962 American Modeler magazine. 15 pages were

devoted to describing just about every aspect of model building and flying

- free flight gas and rubber; control line stunt, combat, scale, and speed;

helicopters and ornithopters; indoor gliders, stick and tissue, and microfilm;

even some early radio control. In order to keep page length here

reasonable (because of all the images), the article is broken into a few

pages. Pages: |

10 & 11 |

12|

13

|

14 |

15

|16

|

17 |

18

|

19 |

20

|

21 |

22

|23

|

24 | For Non-Modelers: All About Air Modeling

20 Easy Ways to Go Crazy! <previous> <next>

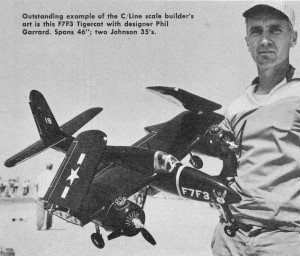

Outstanding example of the C/Line scale builder's art is this F7F3 Tigercat

with designer Phil Garrard. Spans 46"; two Johnson 35's .

Tiny radio controlled low-winger has 27" span; push rod escapement;

.049 engine; weighs 10-1/2 oz.

Chuck glider will do stunts.

Class B free flight gas model above spans 128 inches, uses maximum size

engine, McCoy .60 c.i.d.

Just as free flight models have taken on specialized design characteristics,

so have control line models. There are highly specialized speed, stunt,

racing combat and Navy carrier and scale types. First step into control

line flying for the newcomer should be with a simple Trainer. As experience

is gained he can then progress to the more complicated and demanding types.

C/L TRAINERS - The inexpensive control line trainer

kits available today reduce the model to its bare essentials. Nearly all

feature profile fuselages. Construction is all solid balsa. Most have wings,

tails and fuselages shaped to outline and cross section. Noses are reinforced

with plywood for engine mounting. Everything else - landing gears, control

system - is out in the breeze, mounted on the outside of the model. Main

parts are easily cemented together and doped. The all-balsa construction

makes the trainer a rugged model, able to stand up through repeated hard

(beginner-type) landings. Trainers usually are heavy, so they fly slowly

giving a flyer a chance to learn proper control handling. Flight performance

is limited to up and down and round and round; no stunting, please.

Trainers range in size from 18" span 1/2A powered models to larger 30"

and 36" span types for .19, .29 and .35 engines. Flying lines can be 20

ft. long Dacron line for 1/2A's and 50 to 70 ft. steel wire for larger models.

Unless you are blessed with a smooth hard-surfaced flying site we recommend

starting off with the larger models, since their weight and larger wheels

enable them to roll easily over rough grass or dirt, making take-offs and

landings easier. The little ships can trip up and be blown about readily

in any wind. If possible try to get an experienced control line

flyer to help you through those first flights. He can stay in the center

of the flying circle with you and guide your hand and arm through the proper

"up" and "down" control movements. The new flyer invariably tends to over-control

so if an experienced hand is standing by he can usually save you from pranging

your new model first time out. So if you want to get into control

line flying, start with a simple trainer, don't buy a complicated, fancy

scale job. The object is to get in on the flying fun, and a trainer will

get you there the quickest. You'll have few if any construction problems

and can easily learn engine operation, care of flying lines and control

technique. C/L SPEED - This highly specialized

phase of control line flying is to modelers what drag racing is to car fans.

The object is to extract the last ounce of power from engine and fuel to

go as fast as possible. At present speeds of over 90 mph are flown by 1/2A

powered models and larger engine classes turn in 100 to over 160 mph marks

in competition. This is really whistling around a 70 ft. radius circle and

is definitely not for beginners. Speed models are flown in four

classes according to engine size: Class 1/2A, up to .050 cu. in., Class

A, .051 to .1525 cu. in., Class B, .1526 to .300 cu. in., and Class C, .301

to .655 cu. in. One other class, Proto speed, is limited to .1526 to .30c)

cu. in. engines; more on Proto later. All speed flying competition

has definite rules governing length of flying lines, wire diameter, pull

test, size of handle and number of laps to be flown, timing methods, etc.;

see A.M.A. regulations. The basic rules apply to all and have resulted in

specialized model design. Construction is rugged and models are

built of hardwood, plywood and cast metal parts with very little balsa being

used. Designs are super-streamlined with very thin wings and the minimum

sized airplane is used that will maintain stability and control. Example:

A typical Class A .19 powered speed job has about 14" span and length. The

biggest, .60 powered have only 20" span. Engines are completely cowled in

to aid streamlining. Engines are hotted-up, special fuels are used and small

high pitch props let the RPM really scream. Spinners are universally employed,

hand cranking is sometimes done but starting is usually with aid of a portable

electric motor and storage battery. Electric motor shaft is fitted with

a short rubber hose with end open and clear. Model spinner is held into

revolving hose and friction turns over model engine. High rpm starting can

be hard on fingers. <previous> <next>

Posted December 25, 2010

|