|

An

extensive article introducing non-modelers to aircraft modeling

appeared in the Annual Edition of the 1962 American Modeler magazine.

15 pages were devoted to describing just about every aspect of model

building and flying - free flight gas and rubber; control line stunt,

combat, scale, and speed; helicopters and ornithopters; indoor gliders,

stick and tissue, and microfilm; even some early radio control.

In order to keep page length here reasonable (because of all

the images), the article is broken into a few pages. Pages:

|

10 & 11 |

12|

13 |

14 |

15 |16

|

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |23

|

24 | For Non-Modelers: All About Air Modeling

20 Easy Ways to Go Crazy! <previous> <next>

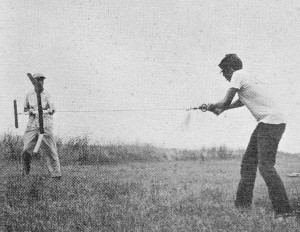

Here's an event that takes muscle and guts: stretch-winding

rubber motor for Wakefield class at National meet.

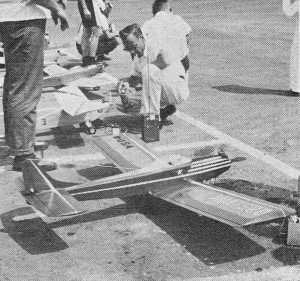

"Viscount" full-house radio plane by Harold deBolt features

steerable nose wheel, is "free-lance" design.

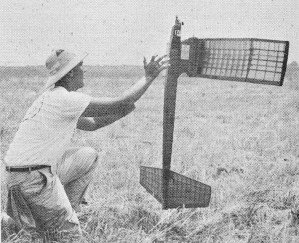

Vertical take-off (VTO) launch demon-strated by Class A free

flight craft; it has .15-size motor.

Model requirements are not too extensive; most important, bonus

points are awarded if it is a scale model of a U. S. Navy carrier

aircraft. Maximum wing span allowed is 44 in.; any size engine can

be used but must correspond to thrust type used on prototype aircraft

if model is a scale job. Model may have fixed or working retractable

landing gear. An arresting hook must be fitted but cannot be longer

than 1/3 the fuselage length. Most popular model types are

scale versions of the prop-driven WW-2 and postwar aircraft, There

are numerous scale kits for these types, spans range from about

30" up to maximum allowed 44." Engines with throttles, .35 to .60

cu. in size are favored. Throttle, wing flap, arresting hook and

rudder controls are used in various combinations and operating systems

are usually developed by the individual modeler. Scoring

in competition is divided into four phases. Model must take off

successfully from free-roll area of deck. Model is then timed for

7 high speed laps. After slowing it is timed for 7 slow speed laps.

When these laps are finished model must then make an arrested landing

on the carrier deck. Scoring is scaled for normal 3-point attitude

landing, arrested landing in other than 3-point attitude and if

model ends up on its back or with one wheel off deck.

C/L PRECISION ACROBATICS - Ever since Jim Walker

turned that first loop with his Fireball, precision acrobatics (or

"stunt" as it is usually called) has been the most popular part

of control line flying. Stunting a yoyo model is a really challenging

sport and gives a flyer .an opportunity to develop and polish his

flying skill and timing. The happy fact about stunt flying is that

the flyer has the best view of his model's antics. Stunt

maneuvers are patterned directly after those done in real aircraft,

with the exception that lateral rolls cannot be done because of

the limitation of the flying wires. (Walker once rigged a frame

around his Fireball permitting honest-to-gosh slow rolls). As a

matter of fact, many model stunt maneuvers would be impossible to

perform in a real airplane. The model stunt maneuvers that

are done make an impressive list: Wing overs, inside loops, inverted

flight, outside loops, inside and outside square loops, horizontal

eights, vertical eights, hourglass figure, overhead eights and a

real toughy, the four-leaf clover, Dizzy yet? It sounds terrifying

and it is at first, but you don't just go out and fly the whole

routine right off. This is the fun of stunt flying, you can start

with the simpler maneuvers, master them, and then try tougher ones

as your technique improves. All the maneuvers are based on the loop,

the more difficult are a series of loops linked together in various

combinations. Here's where the precision part comes

in. It is not just sufficient to flip your model over on its back,

then snap it' back level again ... your loop will be pretty lopsided

or egg-shaped. The idea is to make the model flight path a neat

round circle, finishing at the same altitude as started and not

exceeding a specified angle above the ground. Precision

acrobatic competition rules have definite limits of airspace to

be utilized for each maneuver (see A.M.A. regs), The maneuvers must

be done in a given sequence and scoring is based on ability to perform

maneuvers smoothly, at proper heights and of correct shape. Takeoff

and landing are also graded for scoring. One other feature of competition

scoring is the judging of the model's appearance. Points awarded

for workmanship, realism, finish and originality are added to the

flying score. Competition flying is generally divided into flyer

age groups rather than model or engine divisions. Junior, up to

16 years; Senior, 16 to 21, and Open, 21 and over. There

are stunt models for every engine class but the larger .29's and

.35's are favored for competition, because they have the power to

pull the model smoothly through the wind. large .60 powered ships

fly very well but the engines consume a lot of fuel. The smaller

.049 to .15 powered ships make excellent trainers but are tricky

if wind is strong. Stunt models range in size from about 2 ft. span

for 1/2A's to 4-1/2 ft. span for .35's. Wing areas are generous,

employ thick symmetrical airfoils; built-up fabric covered surfaces

are used for lightness. Fuselages are usually sheet balsa planked

and mounts and side doublers are hardwood and plywood. Flying is

done with 25 ft. to 70 ft. long flying lines depending upon engine

size. These relatively light weight, over-powered designs have a

high degree of maneuverability, some can practically turn in their

own length. Although speed IS not the object of stunt-flying, some

models move at 85 mph. Designs are commonly short-coupled tractor

configuration with a few flying wings and pod and boom layouts.

FLYING SCALE - Everybody loves a good scale

model. Other phases of flying may attract more contestants, but

all modelers are fans of flying scale at heart. There have been

more kits and mag plans produced of scale models than any other

type. The appeal of a miniature copy of a real airplane cannot be

denied. After all, this is what the model hobby is really all about-models

of airplanes. Although other specialized model types have evolved,

the scale model is the all-time favorite.

Scale

models are flown. in every type category, There are rubber-powered

flying scales, engine powered free flight, control I ine and radio

control flying scale models. All have their special features depending

upon the type of flying and power plant used. The full range of

aviation history appears in the great variety of flying scale models

available to the modeler. The simplest flying scale, models

are the small rubber-powered type. These have built-up construction

with tissue covering. Spans average 18" to 24". Flight performance

is limited, but they are great fun for sandlot flying. There is

no contest category for these sport flyers. Many of the rubber-powered

designs can be powered with the Pee-Wee engines and flown free flight.

There is contest flying for gas-engine powered free flight

scale models. Interest is limited, since good flying' performance

and scale fidelity are both required. These factors are not always

easy to achieve because not all real aircraft proportions and designs

have good flight stability when scaled down. Most favored types

are the high-wing cabin monoplanes because they have the necessary

inherent stability. Most biplanes also perform well here. Contest

regulations are few: engine size is limited to .20 or under cu.

in., model must R.O.G. and fly for at least 40 seconds. Model is

judged for scale fidelity, finish and appearance. Each part, wing,

tails, interior, etc. is scrutinized and scored. Construction

follows usual light-weight free flight practice but more careful

finishing and detail work is the rule. Models range in size from

30" to 54" span and engines used are .049 to .19 size. Most

popular type of flying scale model is the control liner. Because

of the built-in stability afforded by the control system and flying

lines, practically every type of real aircraft has been copied and

flown in control line scale. There are World War I and " fighters

and bombers, racers, sport planes, transports, twin engine, four

engine and even six engined B-36's. Dyna-Jet powered fighters have

also been built and flown quite successfully. Control line

scale models are built in a wide range of sizes and power plants.

Most popular are single engine types using .19 to .35 engines and

having wing spans of about 30" to 48". largest are the multi-engine

types such as a 7 ft. span B-36 with six .19 engines. Models feature

built-up and semi- solid construction. Fuselages and wings are

usually planked with sheet balsa (depending upon prototype structure)

so that top quality finishes can be achieved. Scale building requires

a high degree of craftsmanship, ingenuity and patience, to produce

a contest winning model. Many modelers spend as long as a year producing

a single model for the big Nats competition. Contest regulations

permit engines up to 1.25 cu. in. size (and Dyna-Jet). Models are

flown on 52-1/2 to 70 ft. lines except 1/2A's which can be flown

on 35 ft. lines. Model must R.O.G. and fly at least 10 laps to qualify

for scale judging. No points are given for actual flight but additional

points are awarded for scale operation during flight of landing

gear, flaps, throttle control, taxiing. Judging of workmanship

and scale fidelity is scored on model's appearance, color and markings.

Each part, fuselage, wings, tails, gear, cowl, is carefully examined.

Contestants must provide authenticated 3-view drawing of the prototype

for judges comparison with the model. <previous> <next>

Posted December 25, 2010

|