|

Amazingly, even

during the Cold War years it was not uncommon to see aircraft modelers from the

"Iron Curtain" countries participating in international contests. Even Commies like

flying model airplanes. Because their societies and politics were so closed and

guarded, getting information about their modeling supplies was darn near impossible

except during events where inspection could be made. Being a generally friendly

bunch of guys, the modelers would share their designs with the Free World, and vice

versa. Then, in subsequent years the Commies would show up with equipment that was

exact replicas of ours - copyrights and trademarks held no legal weight behind the

Iron Curtain. Truth be known, most or all of the participants were probably KGB

agents (or other Commie country equivalents) engaging in extracurricular espionage

activities when not at the flying field. This article from the August 1962 edition

of American Modeler presents an amazing collection of model engine photos and technical

specifications.

Ironically (and sadly), many people today in the U.S. are beginning to view Russia

as more free and tolerant of traditional American-type values than the current U.S.

political climate permits.

Iron Curtain Engines - Da? Nyet?

Red engines - how good are they? Let us

say, right away, that there is no short. easy answer to this question. In the West,

commercially built model motors are, in general, pretty good nowadays ... no manufacturer

can hope to survive for very long if he markets a dud product because competition

is too keen. In the Soviet Union and satellite countries, the entire background

to model engine production is vastly different and it results in some highly divergent

interpretations as to what constitutes an acceptable product. Red engines - how good are they? Let us

say, right away, that there is no short. easy answer to this question. In the West,

commercially built model motors are, in general, pretty good nowadays ... no manufacturer

can hope to survive for very long if he markets a dud product because competition

is too keen. In the Soviet Union and satellite countries, the entire background

to model engine production is vastly different and it results in some highly divergent

interpretations as to what constitutes an acceptable product.

To understand this we must remember, first, that privately owned model engine

factories, on the scale seen in countries like the United States or Great Britain,

just do not exist in Russian and Eastern Europe. Contest engines are built mainly

by individuals or by small groups, usually working under the auspices of an official,

state-sponsored modeling organization. Such a group may consist of six or eight

professionals, designing, building, testing and developing prototypes and then,

in due course, producing powerplants in relatively small numbers - rarely more than

a few hundred, sometimes only a few dozen. In addition, the group may undertake

other  technical work, such as building R/C equipment. technical work, such as building R/C equipment.

Typical of this sort of set-up is the model development center at Brno in Czechoslovakia

where the famous MVVS engines are made. The center was established in 1953 and one

of its first tasks was to produce a racing engine that would put the Czech C/L speed

team at the top of the World Speed Championships. And this it did.

The construction of less specialized types of engines, made in large quantities

for the ordinary modeler, is usually undertaken by state-owned factories. In many

cases, the factories have little or nothing to do with the actual design of the

motors, design and development of prototypes is the responsibility of individuals

or groups and the factory takes over after the test stakes are concluded. The factories

employed to produce the engines are of many types. In some cases they are big industrial

plants, such as the P.Z.L. aircraft factory in Poland and the Carl Zeiss optical

works at Jena in East Germany.

|

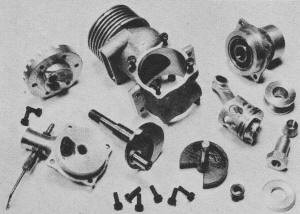

Russian VIP-20 is well-made .15 with disk valve, ball bearing

shaft and lapped piston.

Czech MVVS 2.5/'58 diesel .15.

MOKI M-3 is new .36 c.i.d. stunt motor built by the official

Hungarian model research institute.

Hungarian Krizsma "Record" .15 diesel. Won FAI F/F team championships.

(drawing above)

Production of 10,000 Russian .15 c.i.d. Moscow MD-2.S's is planned.

Has many racing mill features. (drawing above)

Czechoslovakia's MVVS 2.5/1959 racing .15 with Dooling type bypass.

Note big ports in piston. (see drawing and parts & drawing above)

Best East European stunt motor to date is MVVS 5.6; won '58 Internats.

(see parts & drawing above)

Polish Jaskolka-II diesel, made in P.Z.L. aircraft factory; reed

valve, ball-bearing shaft. (see parts above)

Hungarian V.T. 0.25, smallest Iron Curtain mill; 0.015 cu. in.

disp.

|

In other instances, established designs have been freely copied. This is particularly

apparent in Russia where, for instance, exact duplicates of the earlier type Italian

Super-Tigre G.21 0.29 cu. in. glow motor and the West German Webra Mach-1 0.15 cu.

in. diesel, have been produced under different names.

The standard of work turned out by the specialist groups, especially some of

those operating under the state modeling institutes, such as MVVS, or Hungary's

MOKI, is usually high. This does not always hold true for the quantity-produced

factory items. In some cases it appears that production has been assigned to plants

ill-equipped for the production of model motors to the desired standards of quality

- standards which western modelers take for granted.

In Czechoslovakia, for example, factory-made versions of MVVS 0.15 and 0.29 cu,

in. racing type glow motors began appearing under the name "Vitavan" during 1956-57.

Although these engines had all the technical features of the MVVS prototypes (ball-bearing

shafts, ultra-light ringed pistons, disk-valve induction) they lacked precision

and, as a result, failed to approach the performance of the MVVS originals. A production

of 5,000 units per year was estimated for these engines, but it seems extremely

doubtful if this was ever reached. The Czechs then adopted a change of policy, taking

on more employees at the MVVS center and embarking on a program of limited quantity

production in the center's own workshops.

Apart from the sources mentioned, a few engines have also been produced privately

in small workshops owned by one man or a family. Typical of these were the AMA engines

made by A. Machacek in Czechoslovakia and the East German Wilo and Schlosser engines

produced, respectively, by Willi Otto and the father and son partnership of Max

and Benno Schlosser. In the early post-war years, such outfits turned out most of

the engines available at that time.

From the foregoing it can be seen that up to the present modelers in these countries

have had to look to the research and development centers, like MVVS, for contest-grade

engines but, since the production of such engines is limited, many modelers have

to fall back on less impressive factory-built substitutes. The type of engine available

to an individual modeler is not so much dictated by what he can afford to pay for

it, as by his ability and reputation as a modeler. For example, in 1956, MVVS made

only eight and, in 1957, only four, of their special 0.15 cu. in. racing motors.

These went to selected Czech international speed contestants. Subsequent, less exotic,

but still above average, MVVS productions were distributed to official clubs for

allocation to top grade modelers. More recently, since MVVS began quantity production

on a small scale, MVVS engines have been more widely distributed ... but this is

the exception rather than the rule.

Although the average factory-made model engine produced in Eastern Europe is

not up to the quality and performance of its Western counterpart, nevertheless,

there have been efforts to export some of these engines, not only to countries within

the Soviet sphere of influence and to the uncommitted nations, but to Western countries

as well. The Hungarians and East Germans have been the most active in this sphere

with Alag, Aquila, Proton and Zeiss powerplants. The Hungarian foreign trading organization,

"Artex", placed advertisements in Western magazines and has succeeded in selling

a limited number of engines through wholesalers in England, Australia and some West

European countries.

Up to the present time, sales of East European engines in Western countries have

been small. In some cases, importers have been left with stocks of unwanted engines

when dealers failed to reorder. Nevertheless, there are good reasons for believing

that it would be a mistake to write off the East European model engine industry

as being no potential threat to Western manufacturers. One large West German model

company, for example, is currently selling a range of diesel motors made for them

in Hungary.

Originally, this company wanted a low-priced beginner's engine and bids "Were

invited from various manufacturers.

A British firm quoted approximately $1.70 and was thought to stand the best chance.

The contract, instead, went to the Hungarians, who undercut the British price about

25 percent. East European quantity-built diesels, in fact, are up to 50 percent

cheaper than Western engines of similar type. This may not be too important to the

average Western modeler who may have to pay (by the time import duties are added)

nearly as much as for a domestic product. But it could mean that we may find unexpected

competition for our products in less highly developed countries. On the other hand,

so long as we have manufacturers such as Cox, who, by the use of advanced, highly

mechanized production methods, can turn out a better product at a lower price than

the low labor cost countries, America can remain the world's biggest model engine

exporter.

Let's have a look at some of the engines which modelers in Russia and the satellite

countries have been using lately. During the past three or four years, we have tested

upwards of a couple of dozen different types of model engines from the East. From

these we have selected ten representative, current examples for examination.

MVVS 2.5/1959. This is the best .15 cu. in. glow engine yet

produced behind the Iron Curtain. The engine, a development of previous MVVS World

Speed Championship winning engines, first appeared in 1959 when about twenty were

made, primarily for Czech speed experts and we secured one of these originals. The

engine created much interest and was subsequently put into limited production. Examples

have since found their way to many countries outside Czechoslovakia. At the last

major international event for FAI speed - the Criterium of Aces held in Belgium

in September 1961 - these motors were used by Swedish, Belgian, Swiss and German

modelers, in addition to the Czech team. A few have also appeared in the U.S. and,

last year, Lt. David Cotton was clocking up to 119-mph in FAI speed with an MVVS,

occasionally hitting as high as 138 on nitro. He threw a rod at Huntsville after

qualifying to fly in the U.S. FAI team eliminations. These performances, we might

add, are just about the best that have been recorded with an MVVS outside the official

Czech team.

Designwise, the MVVS is of the classic racing engine layout with twin ball-bearing

supported shaft, disk-valve induction, a ringed, aluminum piston and a Dooling-type

hemispherical bypass. The piston is a work of art. It has two vast ports which take

up practically all the skirt surface on the bypass side and, complete with rings,

conrod and full-floating wristpin, it weighs only 0.22-oz. In our example, compression

seal provided by the rings is outstandingly good and the motor starts almost like

a beginner's job.

Another interesting feature is the disc-valve, unusual in that it uses a cast-iron

rotor, mounted on a steel shaft drilled for lubrication and running in a long bronze

bearing in the backplate. The engine has the same backplate and inclined carburetor

as an earlier version but this is rotated through 90 degrees to locate the intake

at the bottom. The rotor gives a conventional intake timing of 45-deg ABDC to 45

ATDC. The exhaust and bypass timing is also orthodox with periods of 130 and 110

degrees of crank rotation respectively. The motor has the widely favored Continental

European .15 bore and stroke combination of 15-mm x 14-mm (0.5905 x 0.5512-in).

Weight is 5.1-oz.

On its introduction, the Czechs rated the MVVS 2.5/1959 at 0.38 brake horsepower

at 18,500-rpm, a figure which put it above any Western 0.15 available at that time.

Our own tests indicated an output of 0.35-bhp at around 18,300 on a commercial racing

fuel (30 percent nitro-methane) to which 10 percent extra nitro-methane had been

added. This was with the engine in strictly stock condition and retaining the standard

spraybar in the intake.

Moscow MD-2.5. This Russian built racing type .15 was announced

in 1960, when it was stated that it would sell at the equivalent of about $8.50

and that a production of 10,000 units was planned over a five year period. The Moscow

is obviously based on the MVVS 2.5/1959 just described, presumably adapted to suit

the factory production facilities available. All castings are pressure die, instead

of sand castings and the engine shows a number of production economies which, in

our example, were reflected in somewhat sub-standard construction and performance.

The lightweight, ringed piston was quite nicely made and the cylinder liner was

well finished with cleanly cut ports. However, piston/cylinder fit was poor and

resulted in extremely reluctant starting, necessitating a castor-oil prime to seal

the rings. Also, the ball-bearings were rather a sloppy fit in their housing. As

on the MVVS, the valve rotor is mounted on a 3.5-mm shaft running in a bronze backplate

bush, but is of aluminum instead of cast-iron. An unusual and not altogether satisfactory

arrangement, the inclined carburetor simply plugs into a tapered boss in the backplate

without any set screw or clamp to secure it. Bare weight is 4.8 oz. The engine is

available with either a spinner type prop mounting or a flywheel for boat use.

The Moscow MD-2.5 is nominally rated at 0.30 bhp. However, the best we could

get from our example was barely over .24 using 30 percent nitro racing fuel. We

also checked it against a Cox-Tee-Dee .15 on identical props and fuels and obtained

the following: 8 x 4 Top-Flite Nylon, 13,000-rpm (Tee-Dee, 16,600): 8 x 3 1/2 Top-Flite

Wood, 14,250 (Tee-Dee, 17,600): 7 x 4 Power, 15,700 (Tee-Dee, 19,400).

We accept the possibility that our test MD-2.5 may have been a particularly bad

example. Even so, it is quite obvious that this engine is no threat to the established

top contest .15's at the present time.

VIP-20. This original powerplant takes its name from the initials

of its designer, the well-known Russian free-flight modeler, V. I. Petukov. It is

another 0.15 cu. in. disk-valve, ball-bearing glow engine, but our example was of

much superior finish and performance to the MD-2.5.

Construction features a one-piece cylinder block and crankcase with integral

intake, the valve disk being mounted in the rear and giving a timing of 48 ABDC-46

A TDC. The finely made cylinder sleeve, a slip fit in the main casting, has multiple

ports despite the use of a lapped piston. The piston is unusual, having a flat head

with a curved step type deflector on the bypass side. Resultant exhaust and bypass

periods are 148 and 128 degrees respectively. The engine has a normal type bypass

passage but gas entry into the bypass is supplemented by rectangular ports in the

piston skirt and liner. An unusual detail is the needle-valve and venturi assembly

which allows the needle valve to be installed in any one of four positions, left

or right, upright or inverted.

Claimed output for the VIP-20 is 0.38-bhp at 18,000-rpm on 25 percent nitro.

The test engine did not quite equal this figure but, on 30 percent nitro, was comparable

with a Cox Olympic. Bore and stroke are 15.2 x 13.6-mm (.5984 x .5354-in).

MVVS 2.5/1958 and 25-D. The MVVS 2.5/1958 was the result of

efforts to provide the Czech team to the 1958 World Championships with an FAI 0.15

free-flight diesel comparable in performance with the Oliver-Tiger. This was a twin

ball-bearing motor of which about a hundred were made, but a plain bearing version,

with minor improvements was also put into series production under the designation

25-D. We obtained a 25-D from one of the Czech team members at the 1958 World Championships

and subsequently acquired a 2.5/1958 also. There was little difference in performance

between the two models: both delivered near to 0.30 bhp at between 15,000 and 16,000-rpm

closely approaching the performance of the stock Oliver.

Quite unlike the Oliver in design, the MVVS diesel is a loop-scavenged motor

and may possibly have been influenced to some extent by the Japanese Enya 15-D MkI

which first appeared a year or two earlier. Like the Enya, it features a large diameter

shaft, a divided bypass - and in the 25-D version a cutaway piston skirt on the

bypass side. In addition, it has a distinctive, oblique bypass port which causes

the outside edges of the port to open earlier and close later than the center area.

Both models are well made and easy to handle. Bore and stroke is 15 x 14-mm.

The 25-D weighs 4.7-oz, 0.3-oz less than the 2.5/1958 and about an ounce less than

the Oliver.

Krizsma Record K-6. The Hungarian Krizsma Record .15 diesels

were second only to Oliver-Tigers in numbers used at the big 1960 World Free-Flight

Championships, where they were employed exclusively by the Team Championship winning

Hungarians and also by the Polish team. Two models have been built, the K-6 (with

which this report deals) and the K-8, a ball-bearing version of the same motor.

The design of the K-6 is strictly orthodox: i.e. a shaft valve, radially ported,

plain bearing layout such as has been popular for European diesels for many years.

The standard of workmanship, however, is of an exceptionally high level and we would

rate this the best finished engine that has so far reached us from Eastern Europe.

Die-casting is exceptionally clean, fits are excellent and finish, inside and out,

comparable with the best Western standards. The engine uses multiple large Volume

internal bypass flutes on the pattern of the West German Webra Mach-1. On test we

obtained an output of 0.286-bhp at 14,700-rpm which is very good for a plain bearing

diesel of this size and type. Bore and stroke are 15 x 14-mm. Weight 4.7-oz.

Jaskolka 5G-2.5 Mk.2. The Jaskolka ("Swallow") is one of a series

of model motors designed by one of Poland's best known model engineers and free-flight

modelers, Stanislaw Gorski. It is built at the P.Z.L. aircraft plant.

The model featured is the Series 2 version with reed-valve induction and twin

ball-bearing shaft. The Jaskolka has also been built in plain bearing and rotary

valve models. Cylinder porting is again of the Webra type just described and the

major components, crankcase, cylinder, backplate and head, are threaded assemblies,

no separate screws being used. The carburetor screws into the backplate, clamping

a 0.005" spring steel reed and can be rotated through 360 degrees to bring the needle-valve

to any convenient position. Performance is about average for engines of this type

- around 0.25-bhp-and the motor weighs 4.75-oz.

V. T. 0.25. V.T. stands for Vella Testverek or Vella Brothers.

Andras and Geza Vella design and build the V.T. Alag and Aquila diesel and glowplug

engines in a plant in Budapest and production is reported to be "a few hundred"

monthly. The diminutive V.T. 0.25 diesel is the smallest engine produced so far

in Eastern Europe - half way in size between Cox's Tee-Dee 0.010 and 0.020 models.

It is 1-5/16" high and weighs 5/8-oz. Design and construction follows the same general

pattern as the larger V.T. diesels, except that a cast-iron piston is used in place

of the aluminum one favored earlier by the Vella brothers. This is better, since

the aluminum contra-piston, having a higher coefficient of thermal expansion, tended

to seize in the bore when the motor reached running temperature. A rather unusual

simplification on the V.T. 0.25 is the back cover, which merely presses into the

crankcase instead of be-ing threaded.

Kometa MD-5. This Russian-built glow 0.29 is an exact copy of

the earlier type Super-Tiger G.21 with ringed piston and detachable front plate.

Not so well made as the Italian original, it has been quite widely used by the Russians,

with minor modifications, for stunt, speed and speedboat work. Performance varies

to some extent between individual examples but, from tests we have made, the Russian

claim of 0.50-bhp is not unduly optimistic for a reasonably good example running

on about 30 percent nitro. (This compares with the Super-Tigre rating of 0.80-bhp

at 17,500, for the original which was a trifle exaggerated.)

Crankcase/cylinder-block, front housing and head are all pressure castings, reasonably

well produced but without any surface treatment to improve appearance. The generously

proportioned, unhardened shaft has a 12-mm main journal, a 9-mm gas passage and

is blued on non-working surfaces. It has a big rectangular valve port, registering

with a similar aperture in the bearing, to give a quoted timing of 35-deg ABDC to

70-deg ATDC, although the measured timing on our example was, in fact, 25-55. The

shaft runs in 12 x 28-mm 8-ball inner, and 7 x 19-mm 6-ball outer bearings, the

rear race centering the housing in the case. The pressure cast piston has two rings

and a full-floating tubular wrist-pin. The slip fit cylinder sleeve is well made

with multiple ports cleanly cut. Bore and stroke are 19 x 17-mm (.7480 x .6693")

and the motor weighs 7.4-oz.

MVVS 5.6. The 0.346 cu. in MVVS 5.6 is the most successful East

European stunt engine produced to date. It was designed in 1957 and one was subsequently

used by Josef Gabris to win the world stunt championship for Czechoslovakia in 1958.

Prior to this, on September 15, 1957, a special hopped-up version, reduced to 5cc

displacement, broke the world record for Class II speed models with 151.6- mph in

the hands of Bohumil Studeny, an MVVS employee. More recently, at the Belgian Criterium

in September 1961, Sirotkin of Russia and Herber of Czechoslovakia, both using MVVS

5.6's and competing against the cream of European stunt flyers and the world's best

stunt engines, placed 2nd and 3rd behind the Fox 35 powered entry of World Stunt

Champion Louis Grondal.

The remarkable thing about the MVVS 5.6 is that, except for having a similar

displacement, it is quite unlike the accepted idea of a stunt 35. For a start it

has a ringed aluminum piston, rear disk valve induction and a ball-bearing shaft.

General design, in fact, follows that of the MVVS racing engines except for a near

vertical intake, reduced frontal overhang and more conservative rotary-valve timing

of 50-30. Construction is to the usual MVVS standards. All castings are sand cast

and extensively machined and metal-to-metal joints are used throughout. The engine

weighs 7.25-oz and has a 20 x 18-mm (0.7874 x 0.7087") bore and stroke.

The MVVS 5.6 was designed to operate on

straight 75/25 methanol/castor-oil fuel because of the severely limited availability

of nitro methane in Czechoslovakia. Our engine, on a low (3 per-cent) nitro content

commercial fuel delivered 0.54-bhp at a little over 13,000 rpm. It was extremely

easy to handle and starting was as good as, if not better than, the best conventional

lapped piston 35's. The MVVS 5.6 was designed to operate on

straight 75/25 methanol/castor-oil fuel because of the severely limited availability

of nitro methane in Czechoslovakia. Our engine, on a low (3 per-cent) nitro content

commercial fuel delivered 0.54-bhp at a little over 13,000 rpm. It was extremely

easy to handle and starting was as good as, if not better than, the best conventional

lapped piston 35's.

MOKI M-3. The equivalent of the MVVS center in Hungary is MOKI

and the latest MOKI product is the M.3, a 0.364 cu. in. stunt glow motor. The layout

of this motor is generally similar to that of western stunt 35 class engines. It

uses a unit die cast crankcase and main bearing (the latter bronze bushed) and a

mild steel cylinder with integral fins. The pis-ton is very light and is relieved

below the wrist-pin centers. The hardened, counter-balanced crankshaft has an ll-mm

diam-eter journal and a moderately sized valve port which gives 40-40 induction

timing.

Claimed output for the M-3 is 0.55-bhp at

14,000-rpm on 75/25 methanol/castor. The engine has a bore and stroke of 20 x 19-mm

(0.7874 x 0.7480") and weighs 7.6-oz. Like the Russian glow engines, the MOKI is

taped to take a standard "western" size 1/4 x 32 TPI glow plug, unlike the Czech

MVVS engines which use 6- mm metric thread plugs. Claimed output for the M-3 is 0.55-bhp at

14,000-rpm on 75/25 methanol/castor. The engine has a bore and stroke of 20 x 19-mm

(0.7874 x 0.7480") and weighs 7.6-oz. Like the Russian glow engines, the MOKI is

taped to take a standard "western" size 1/4 x 32 TPI glow plug, unlike the Czech

MVVS engines which use 6- mm metric thread plugs.

In conclusion, it is interesting to note

that while engines from the Eastern bloc countries are seldom seen in the U.S.,

quite a few American and other Western motors have been used on the other side of

the Curtain. In Hungary, especially prior to the advent of MOKI engines, Western

motors have been quite widely employed in contests ... notably McCoy and Super-Tigre

for CIL and Webra for F IF. In Czechoslovakia, the national championships for stunt

and team-racing have twice been won with McCoy and Oliver- Tiger motors. In Poland,

Super-Tigre, O.S. and Webra motors from Italy, Japan and West Germany have been

officially imported for the use of leading contest modelers. And at the last World

Stunt Championships, the two highest placed modelers from the East, Dr. Geza Egervary

of Hungary (5th) and Yuri Sirotkin of Russia (8th) used Veco 35 and McCoy 35 motors

respectively. In conclusion, it is interesting to note

that while engines from the Eastern bloc countries are seldom seen in the U.S.,

quite a few American and other Western motors have been used on the other side of

the Curtain. In Hungary, especially prior to the advent of MOKI engines, Western

motors have been quite widely employed in contests ... notably McCoy and Super-Tigre

for CIL and Webra for F IF. In Czechoslovakia, the national championships for stunt

and team-racing have twice been won with McCoy and Oliver- Tiger motors. In Poland,

Super-Tigre, O.S. and Webra motors from Italy, Japan and West Germany have been

officially imported for the use of leading contest modelers. And at the last World

Stunt Championships, the two highest placed modelers from the East, Dr. Geza Egervary

of Hungary (5th) and Yuri Sirotkin of Russia (8th) used Veco 35 and McCoy 35 motors

respectively.

Russian Kometa MD-S is carbon copy of early Italian Super-Tigre. Moscow MD-2.S

has MVVS features. (see parts above)

Articles About Engines and Motors for Model Airplanes, Boats, and Cars:

|